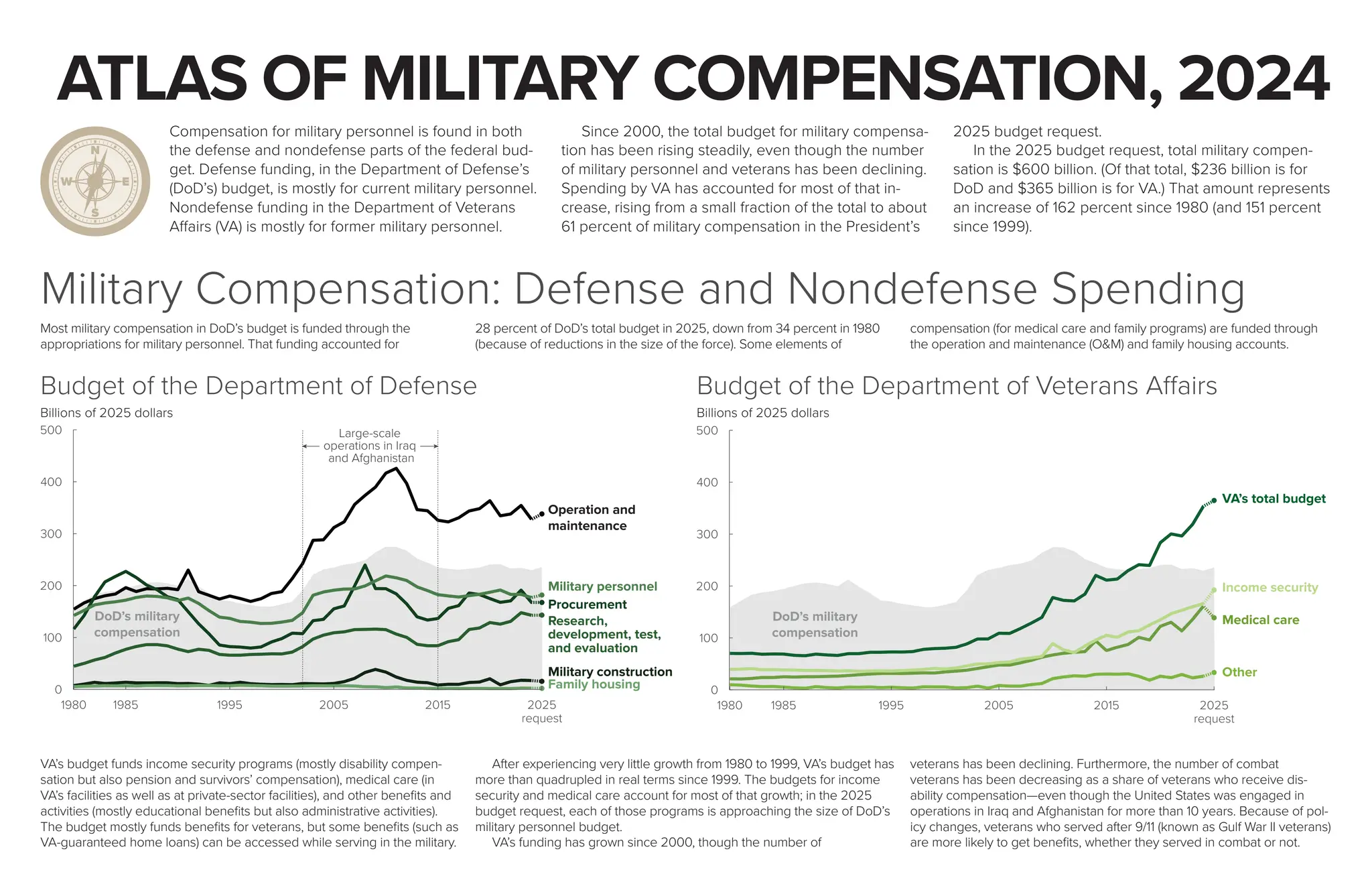

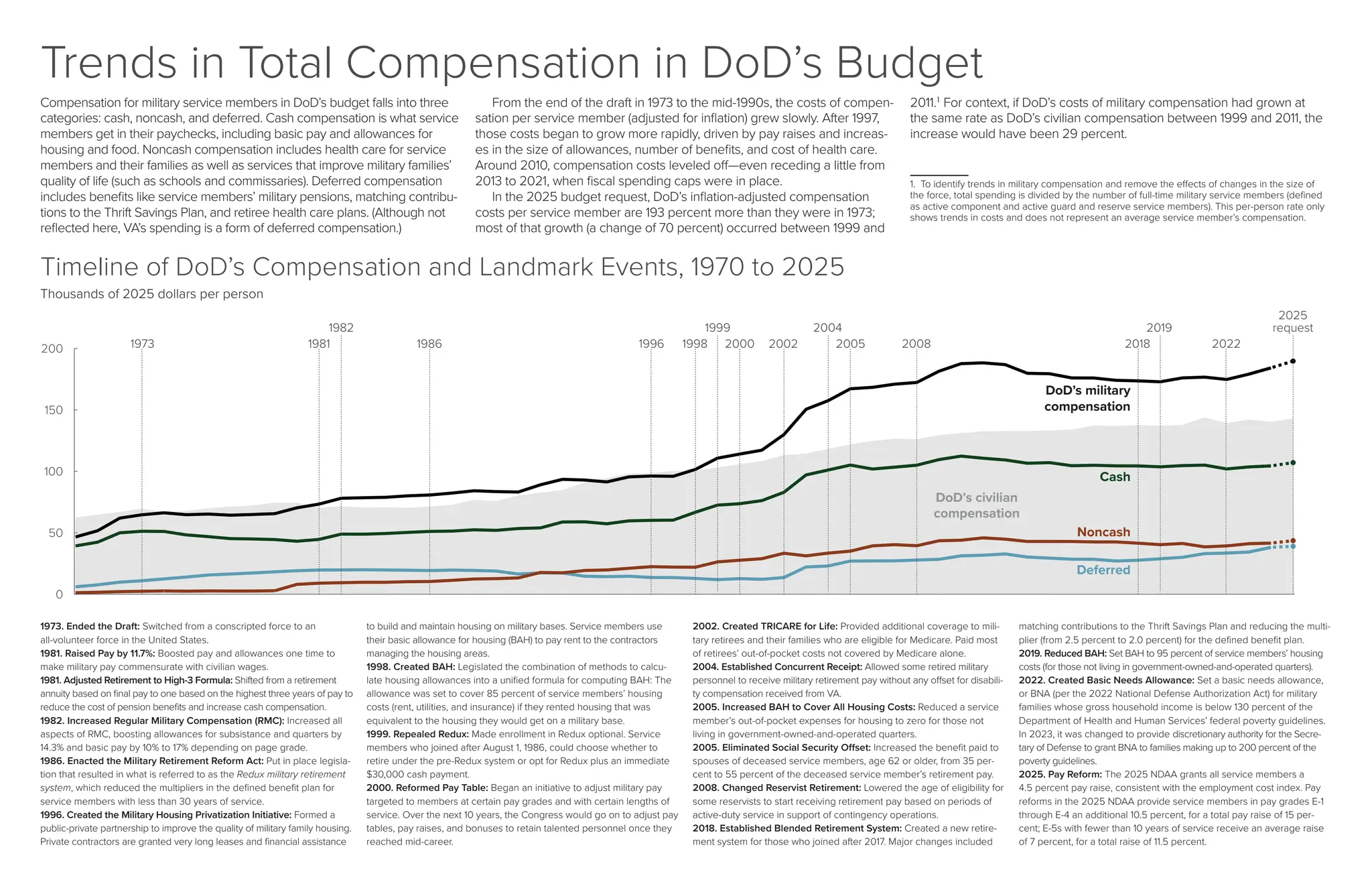

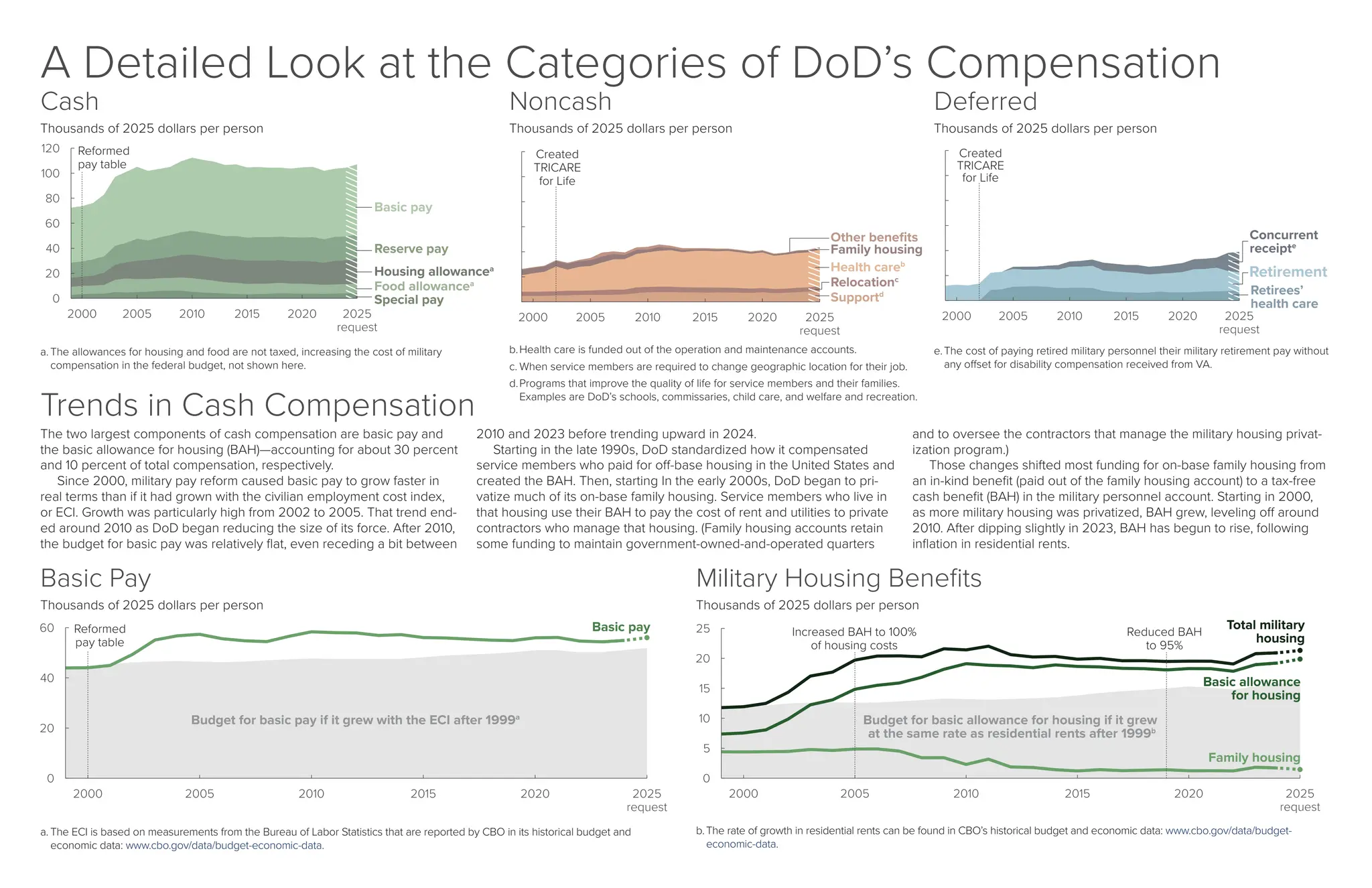

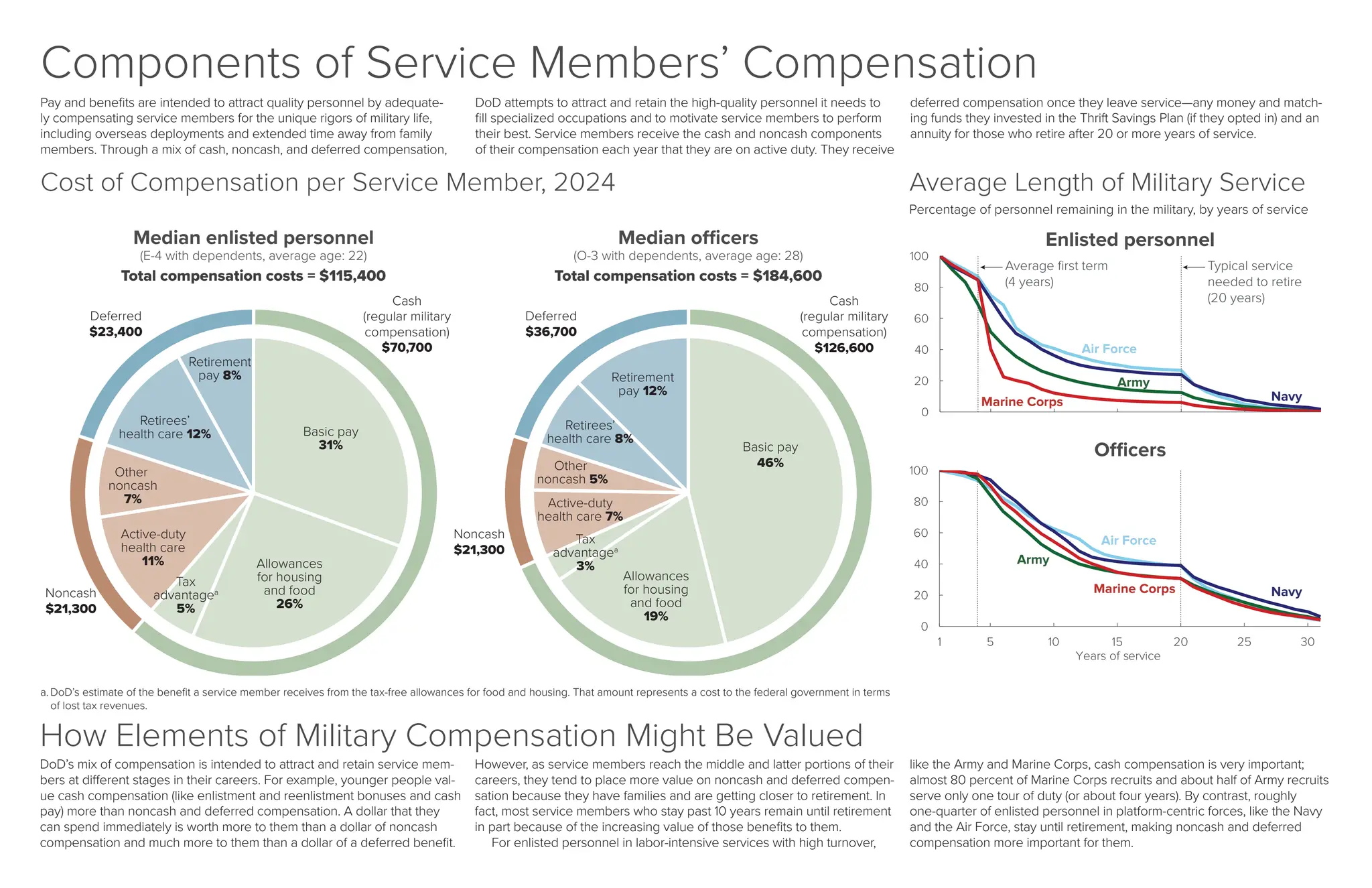

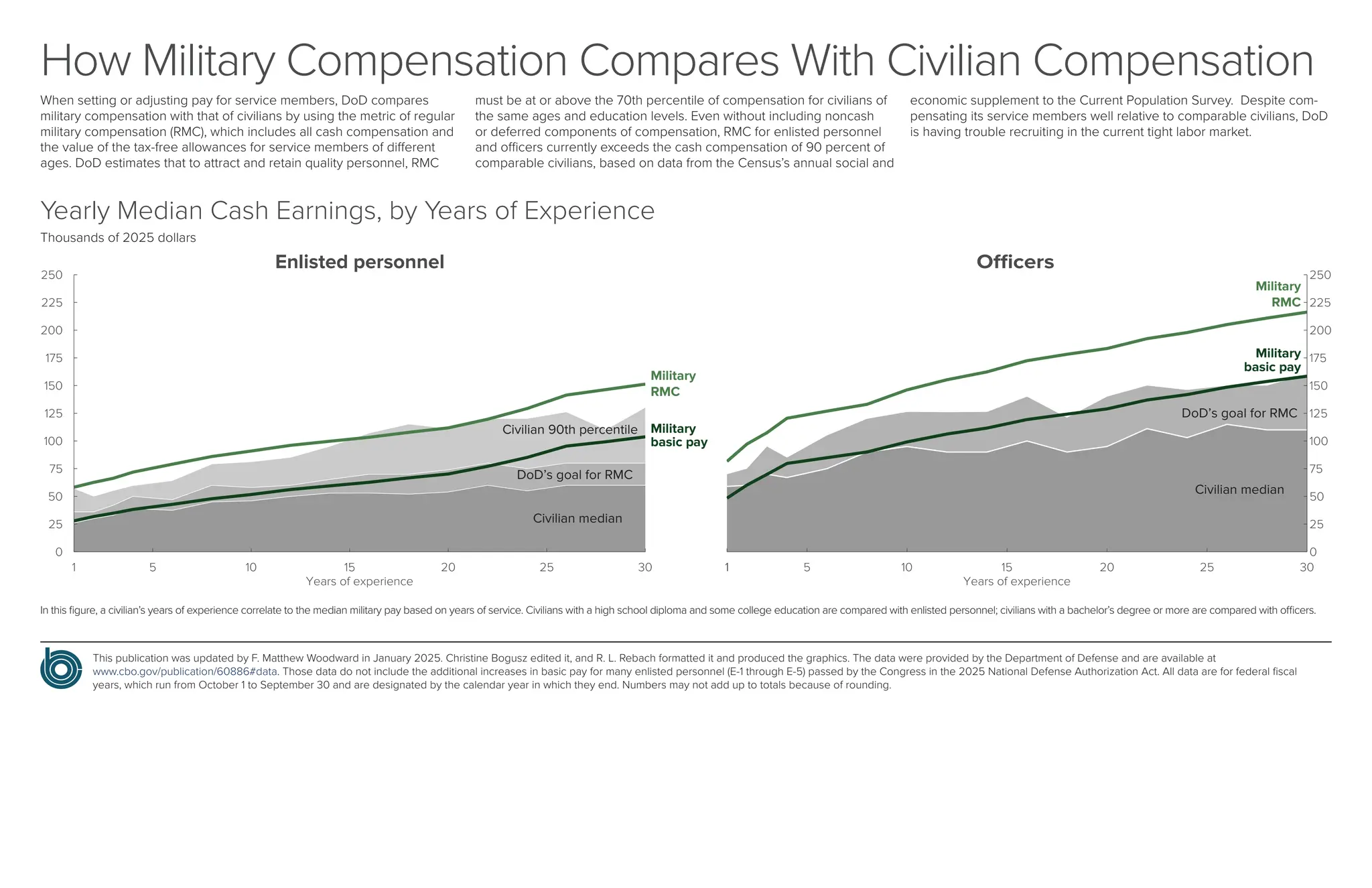

The document outlines the budget and compensation structures for military personnel in the Department of Defense (DoD) and the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) for the year 2025, highlighting a total military compensation budget of $600 billion, with significant growth in VA spending for veterans. Key trends include a shift in compensation to emphasize noncash and deferred benefits, particularly for those who served after 9/11, driven by policy changes and reduced military populations. It details various landmark changes in military pay and benefits from 1973 to 2025, aiming to maintain competitiveness with civilian compensation and meet recruitment and retention objectives.