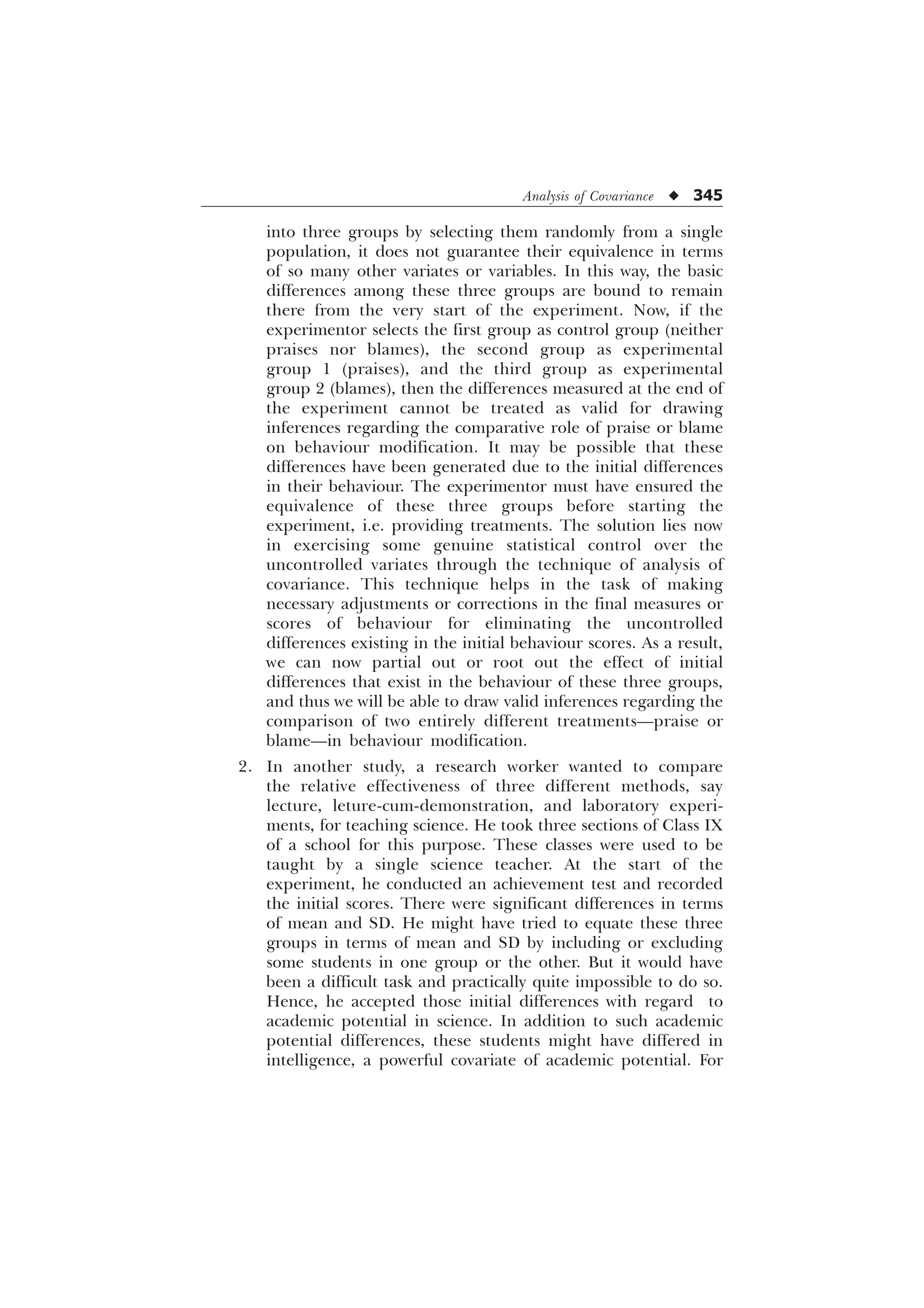

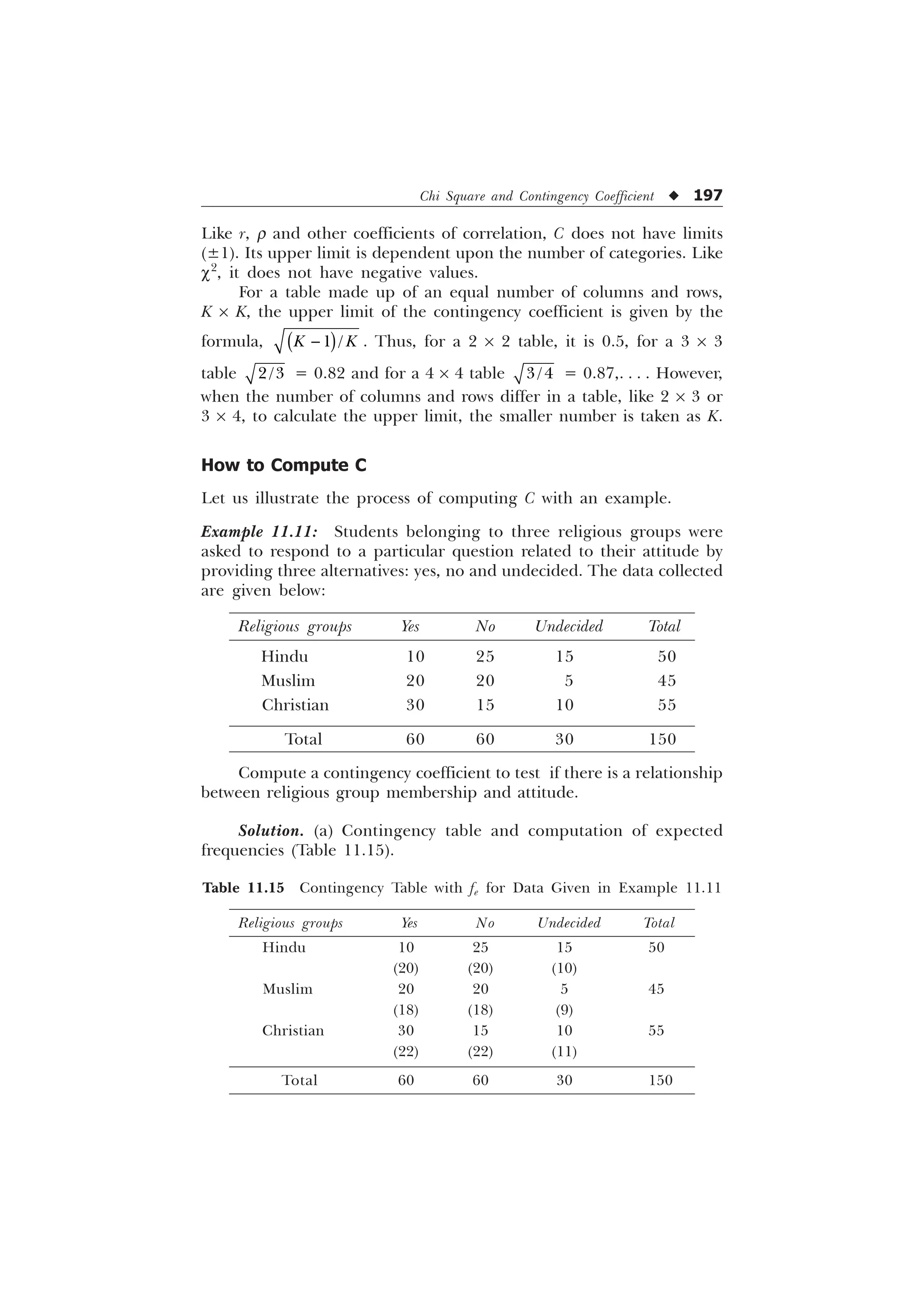

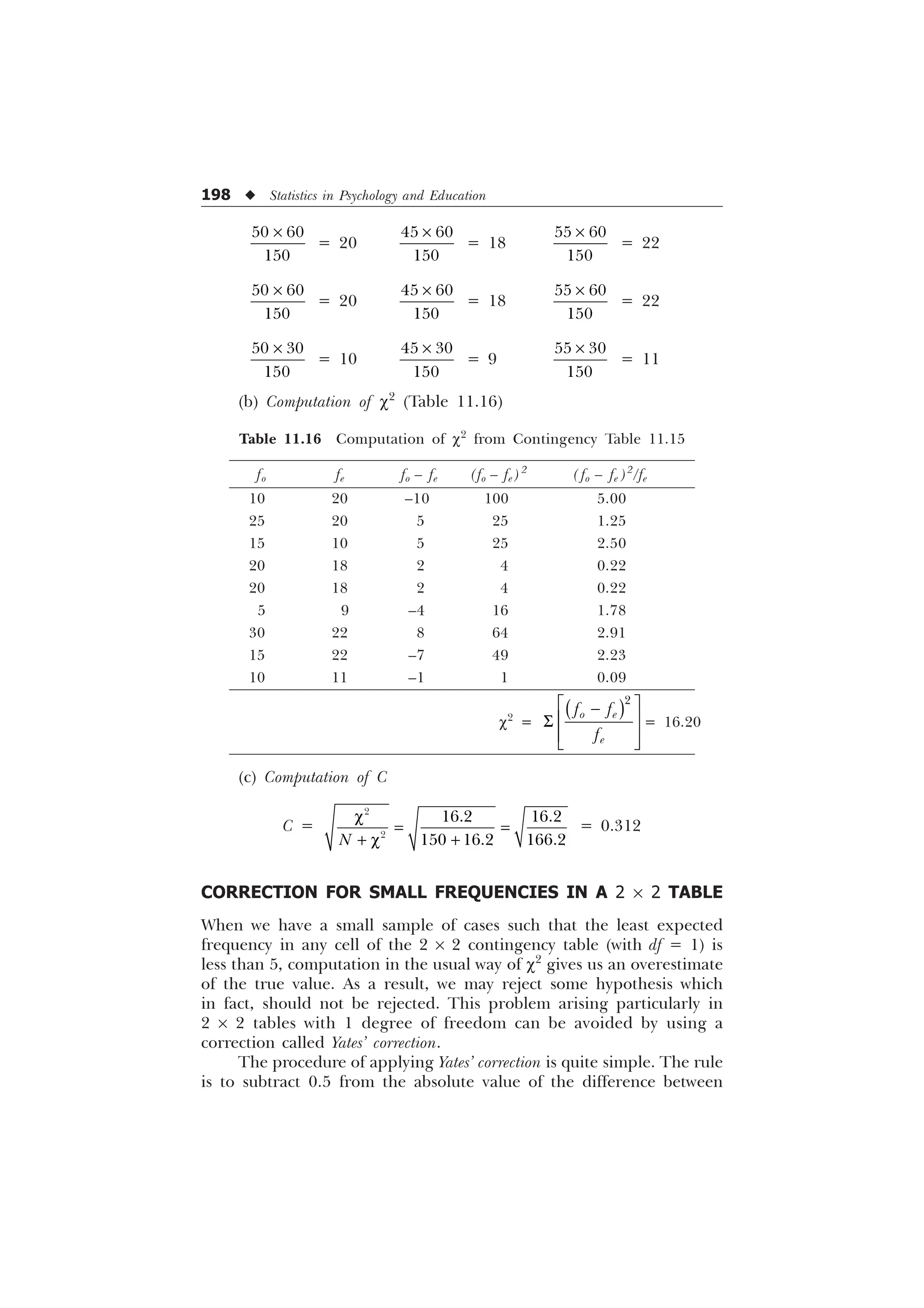

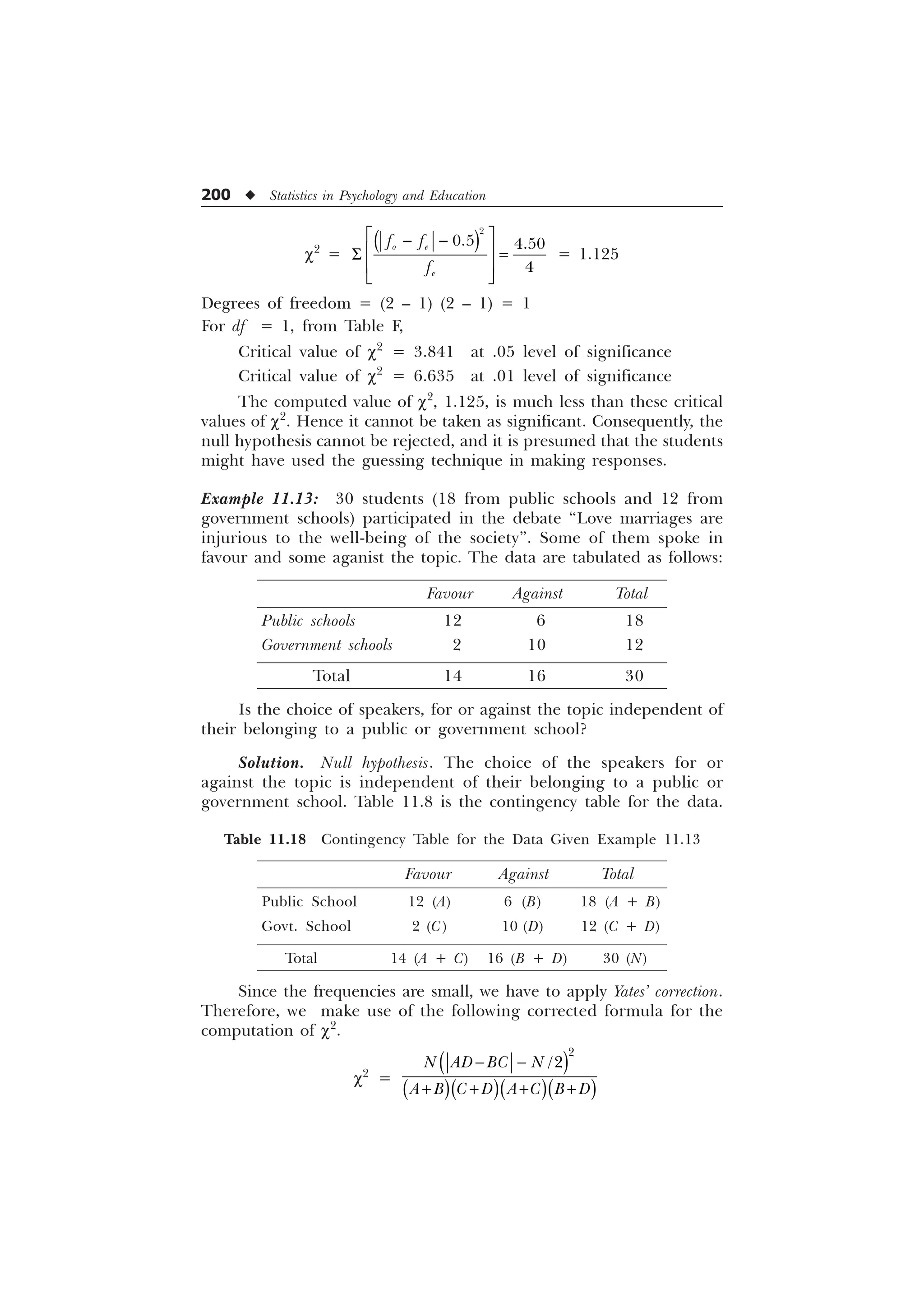

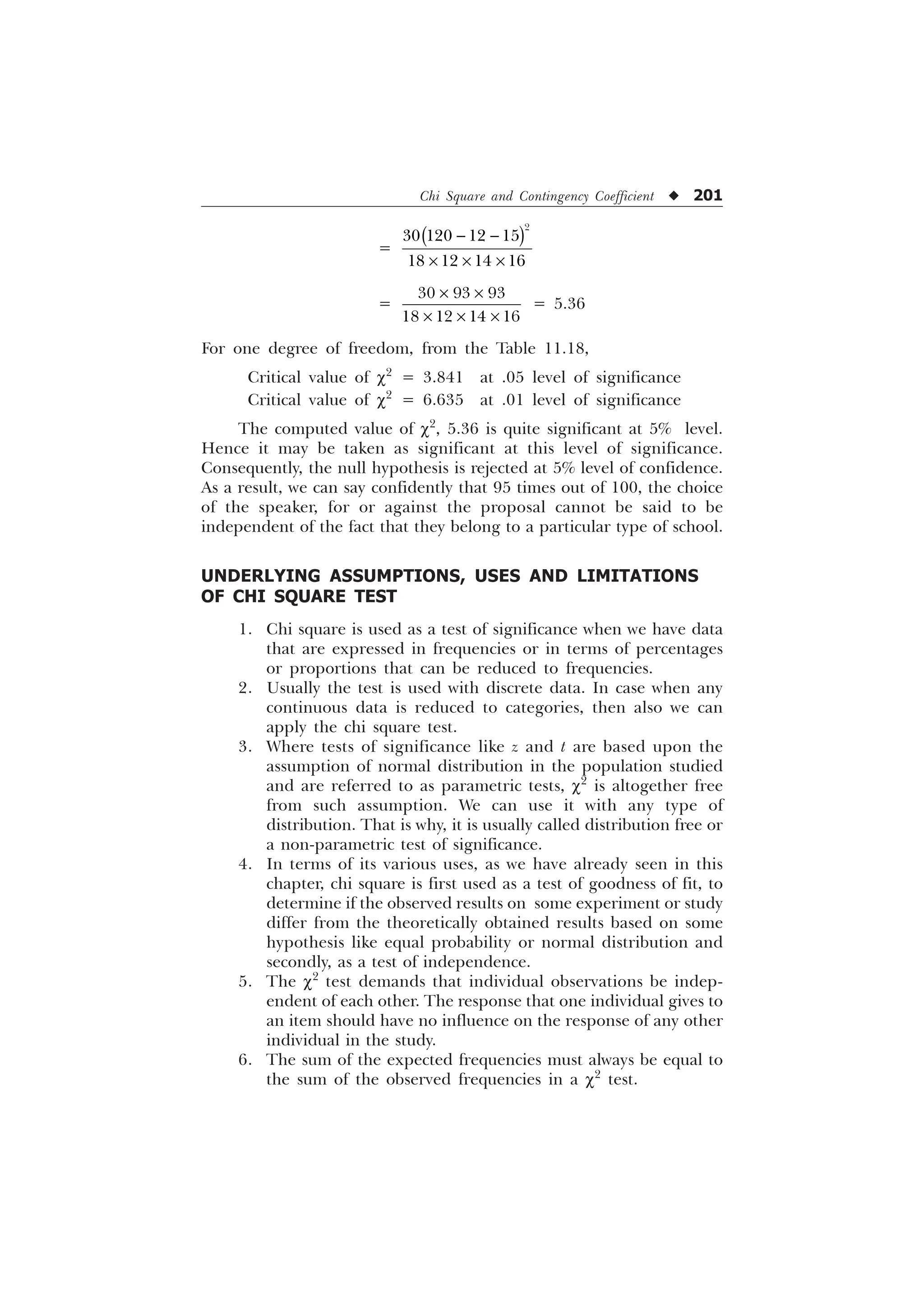

The document is a comprehensive introduction to statistics in psychology and education, authored by S.K. Mangal, and outlines both fundamental statistical concepts and advanced techniques across various chapters. It emphasizes the importance of statistical methods in evaluating and measuring in educational and psychological contexts, along with providing practical applications and exercises for learners. The second edition has been updated with new chapters and revised content to align with current academic syllabi and research areas.

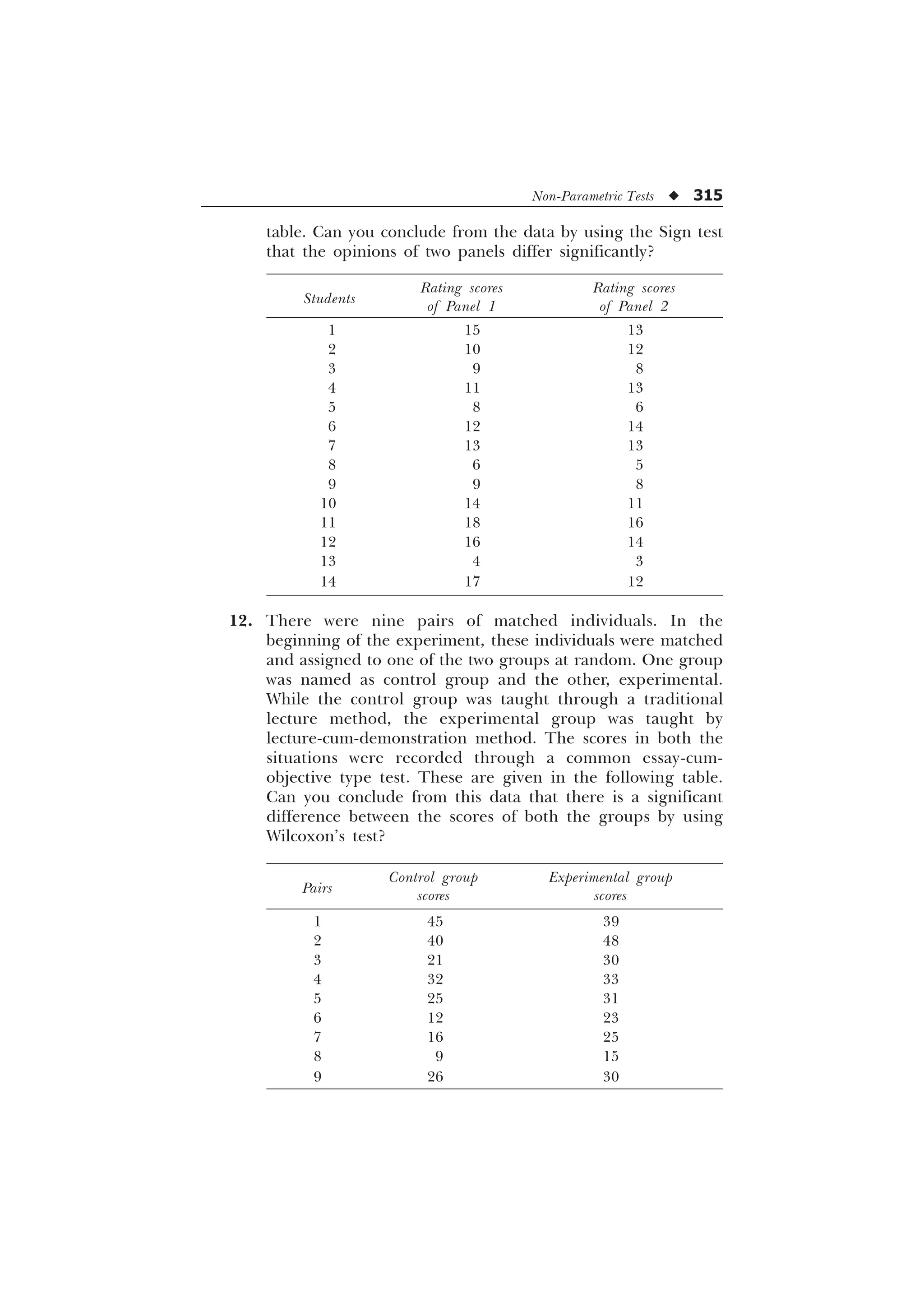

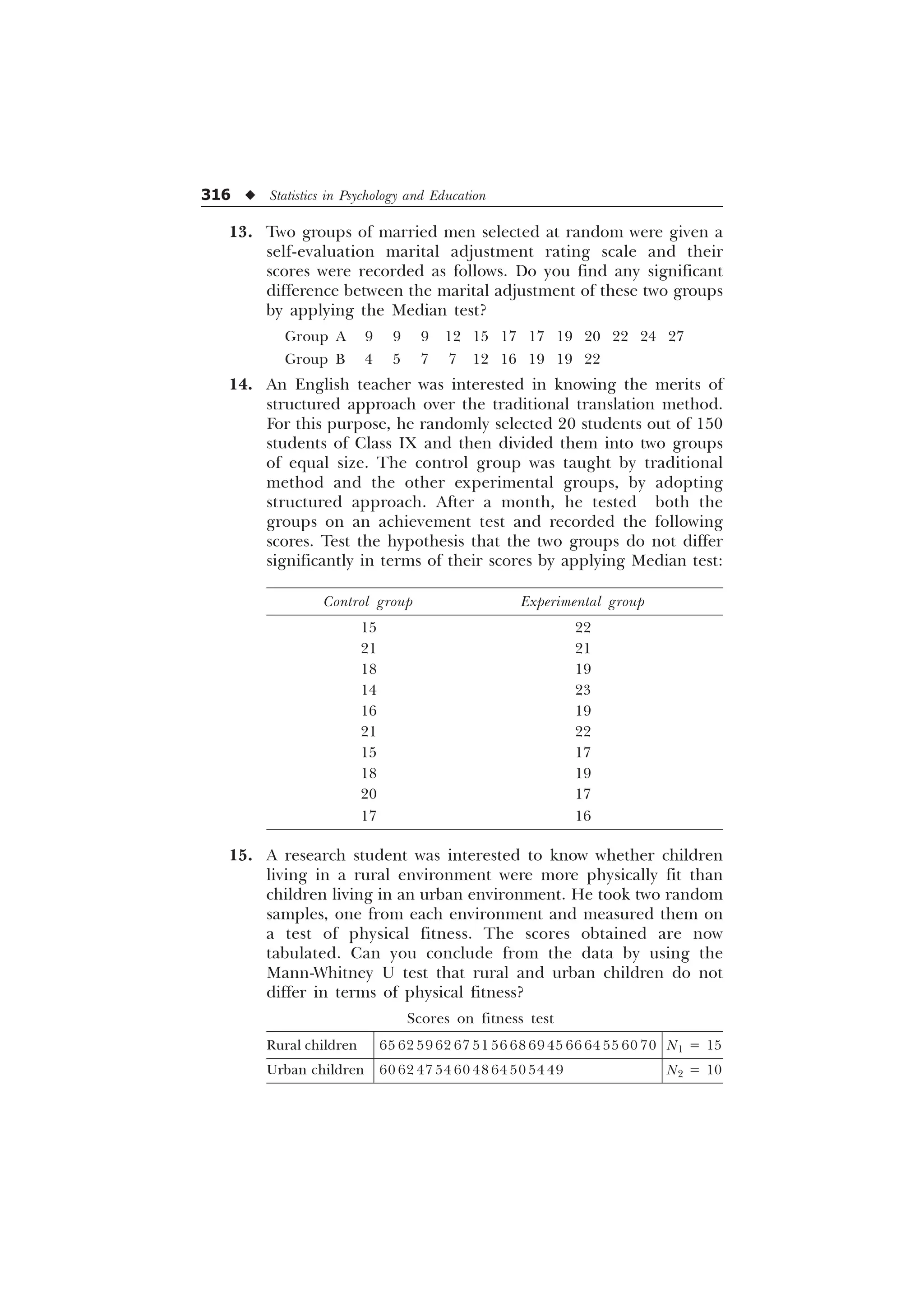

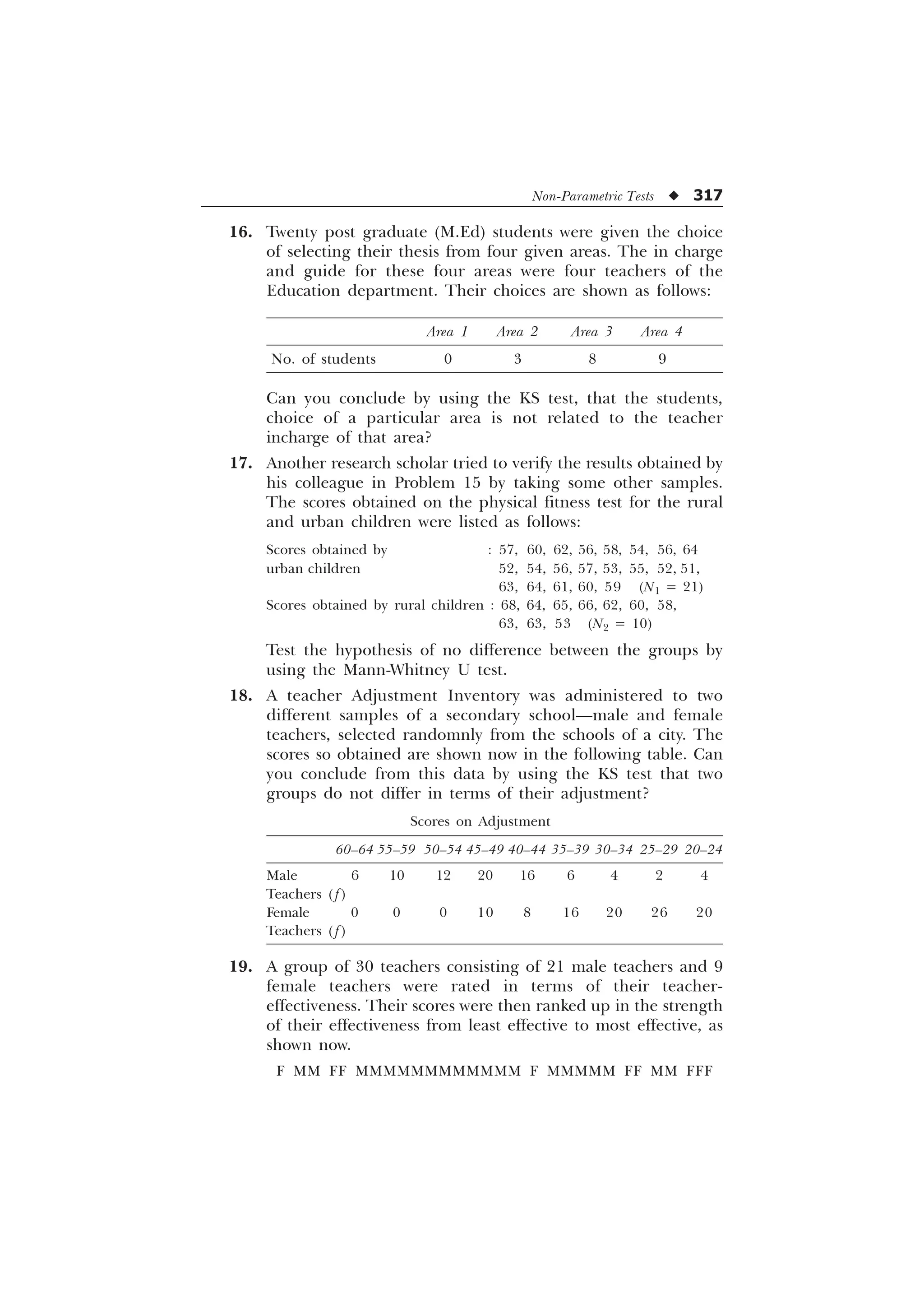

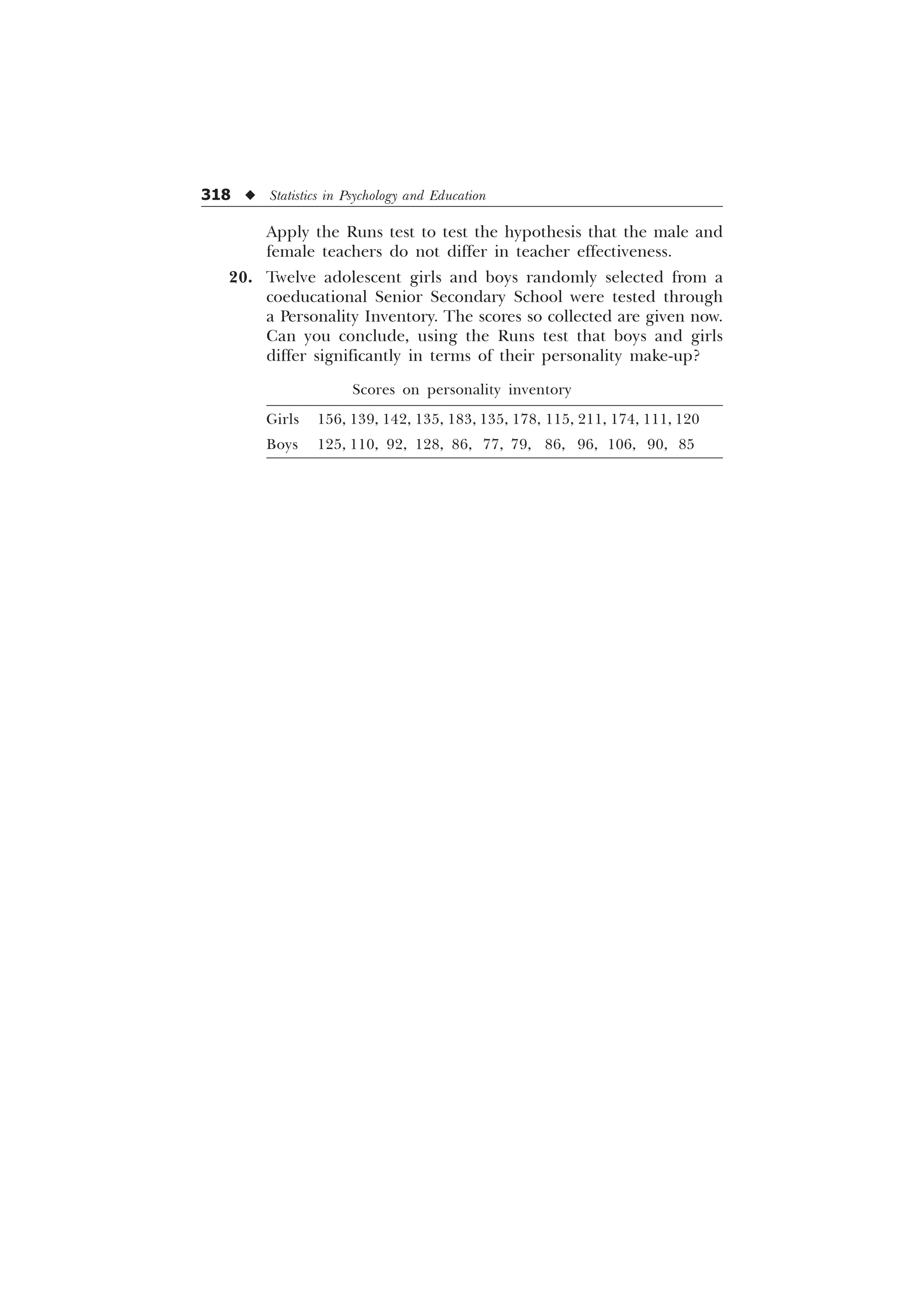

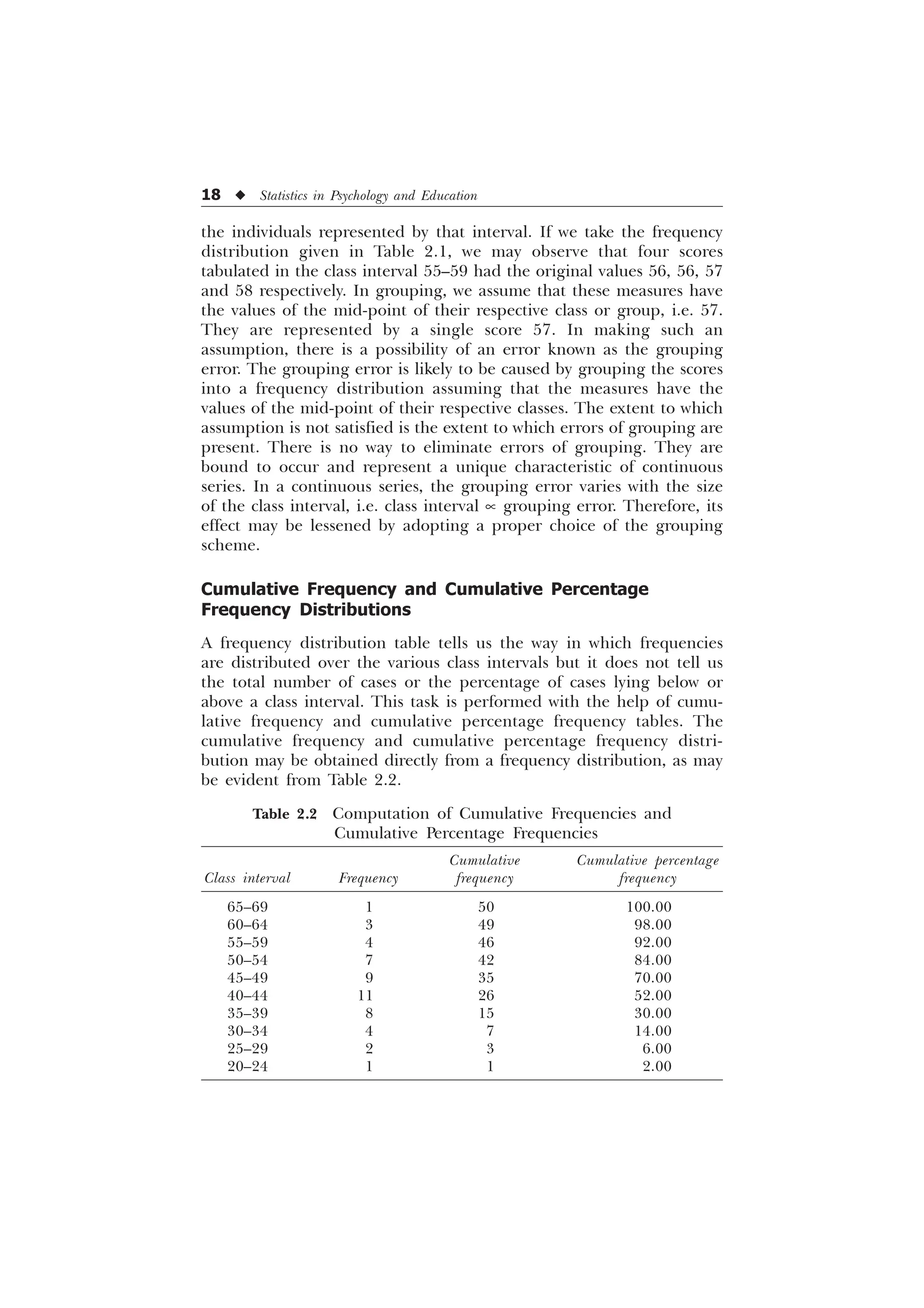

![44 u Statistics in Psychology and Education

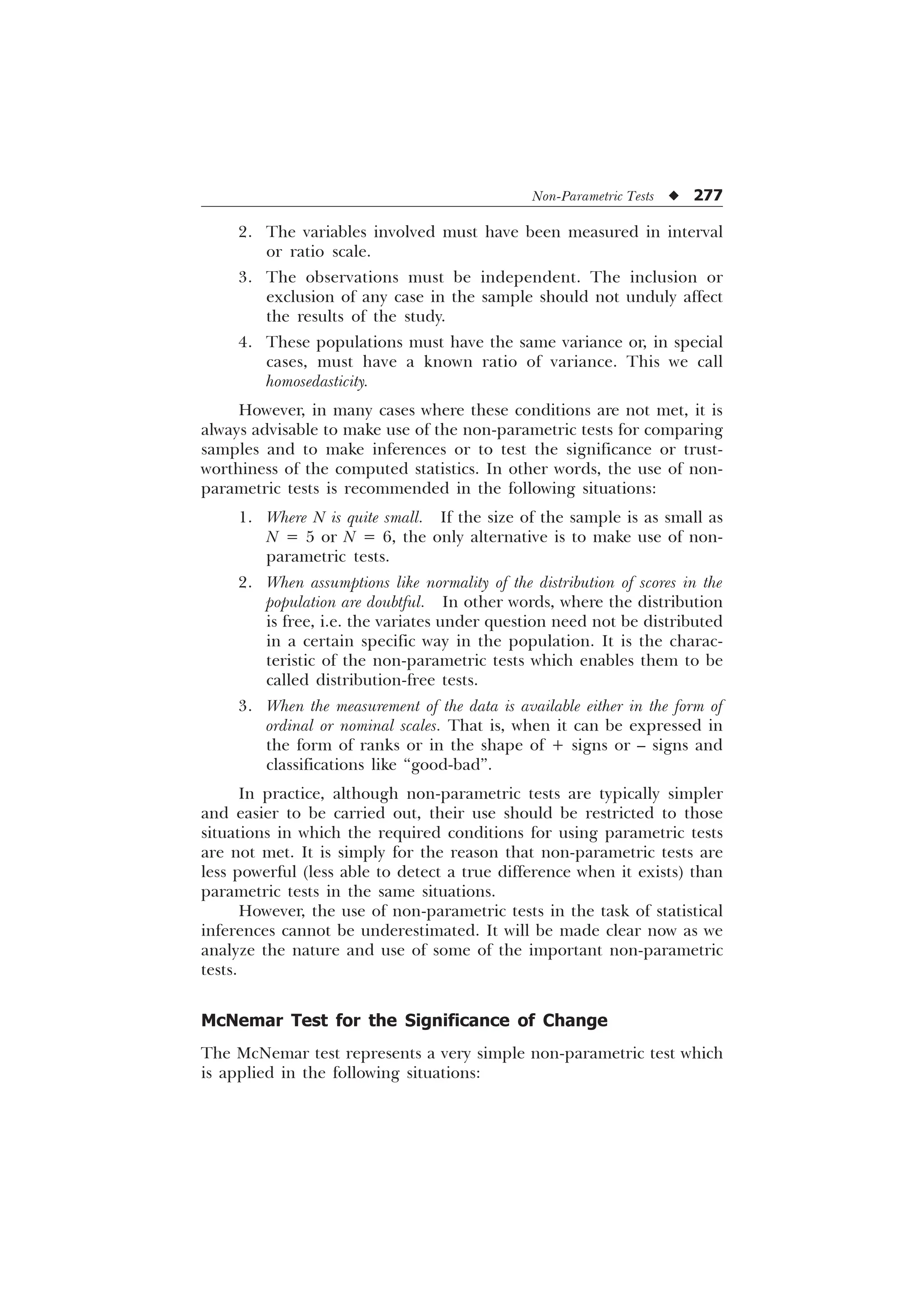

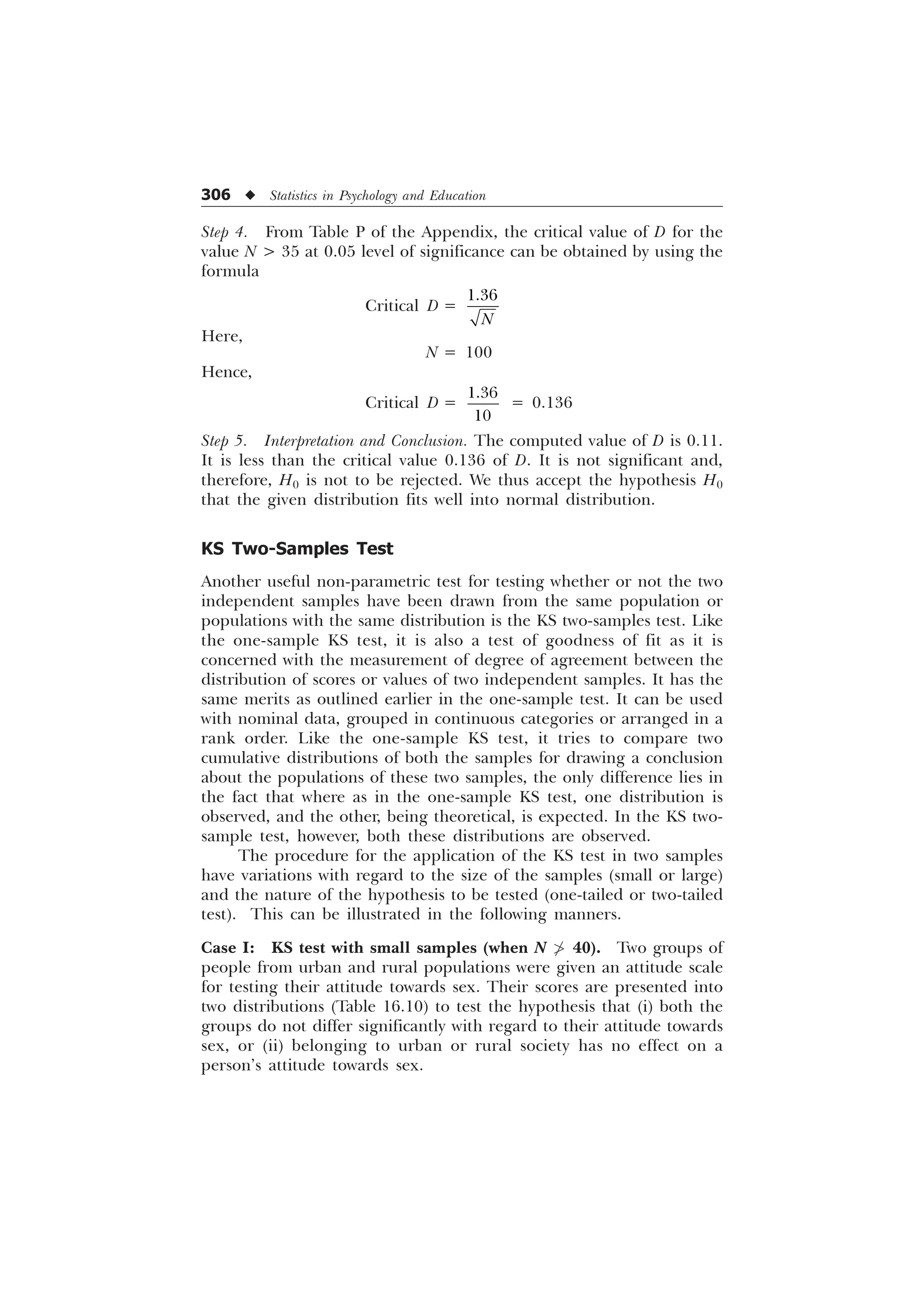

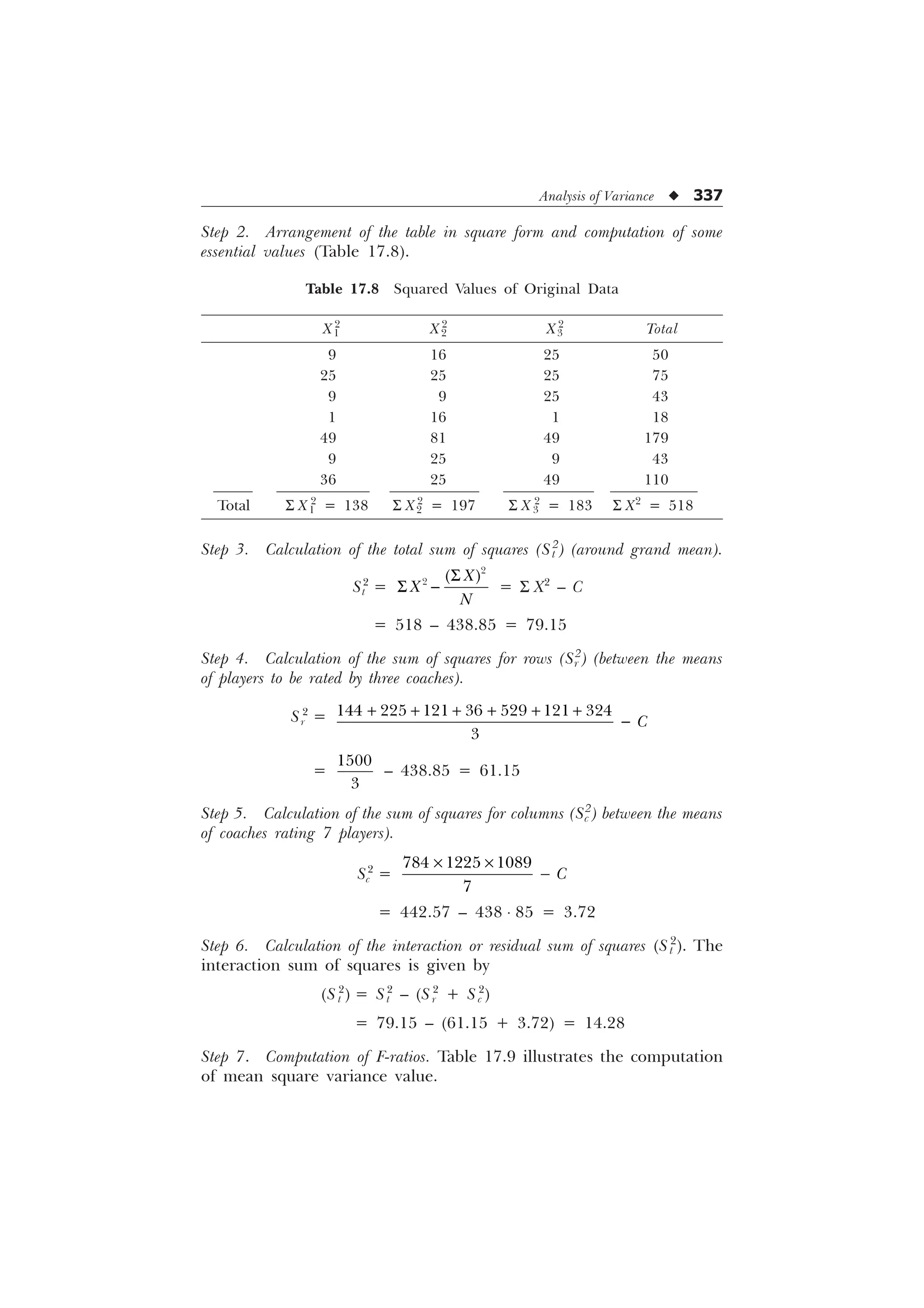

is termed as median. We may thus say that the median of a distribution

is the point on the score scale below which half (or 50%) of the scores

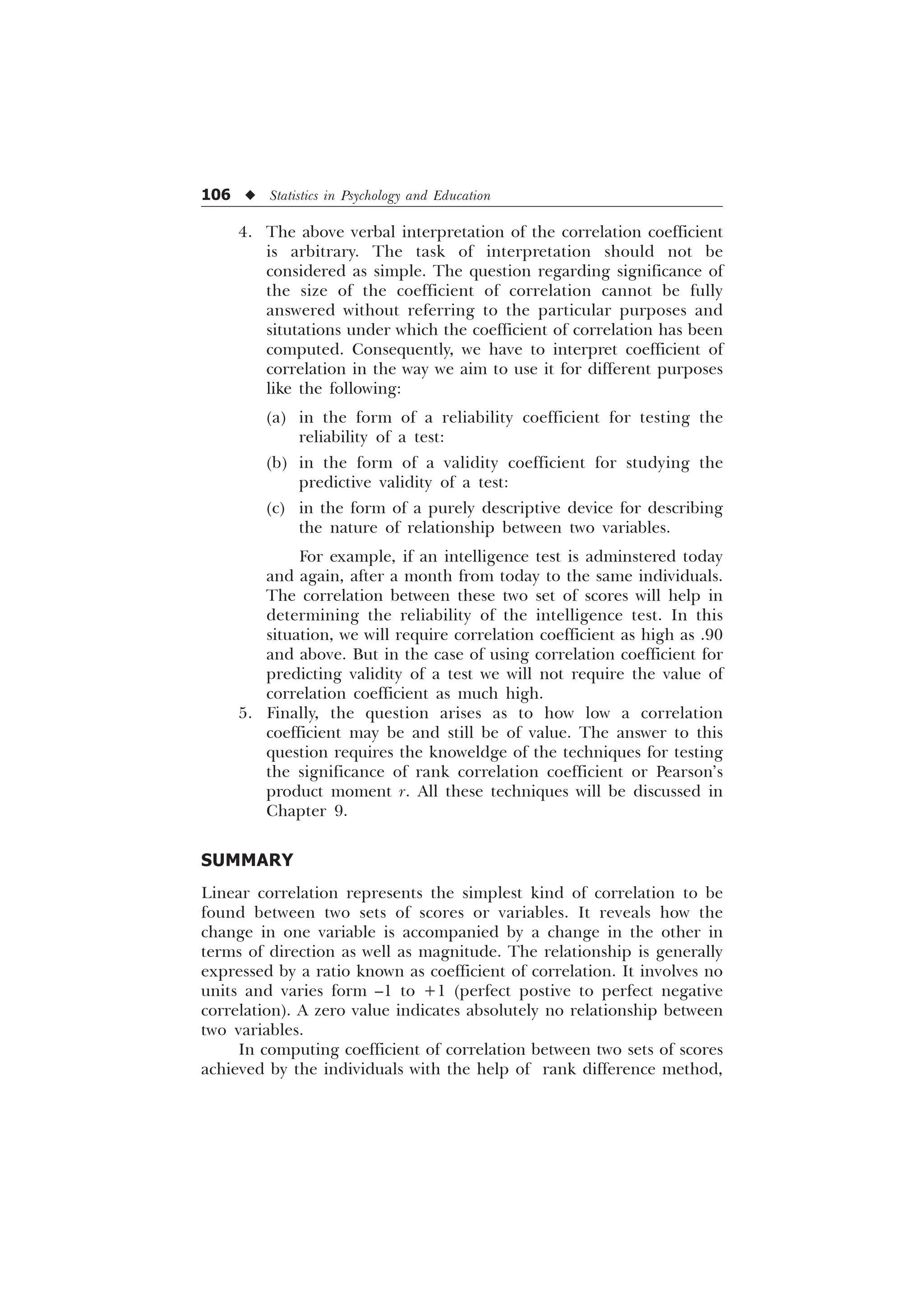

fall. Thus, median is the score or the value of that central item which

divides the series into two equal parts. It should therefore be

understood that the central item itself is not the median. It is only the

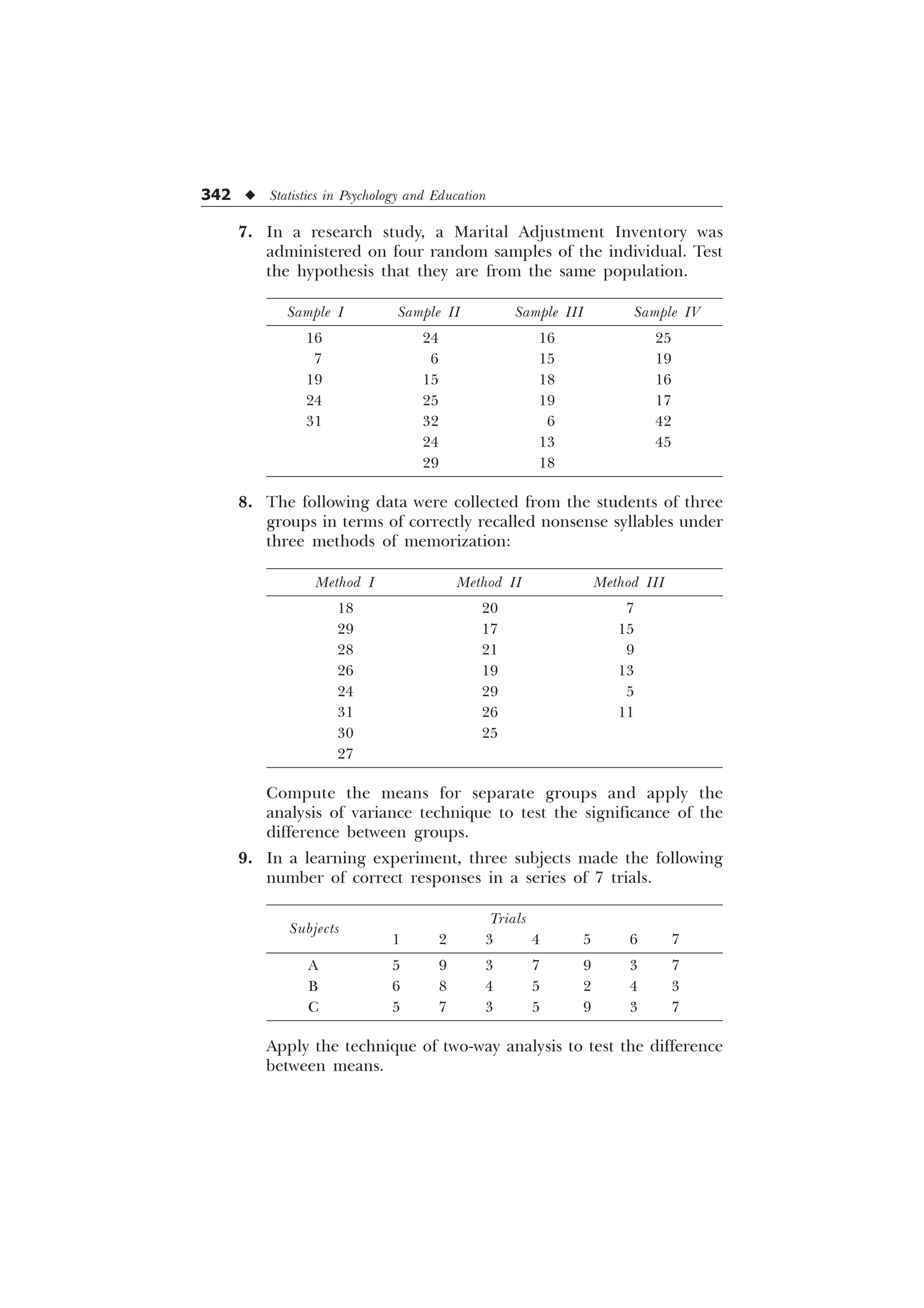

measure or value of the central item that is known as the median. For

example, if we arrange in ascending or descending order the marks of

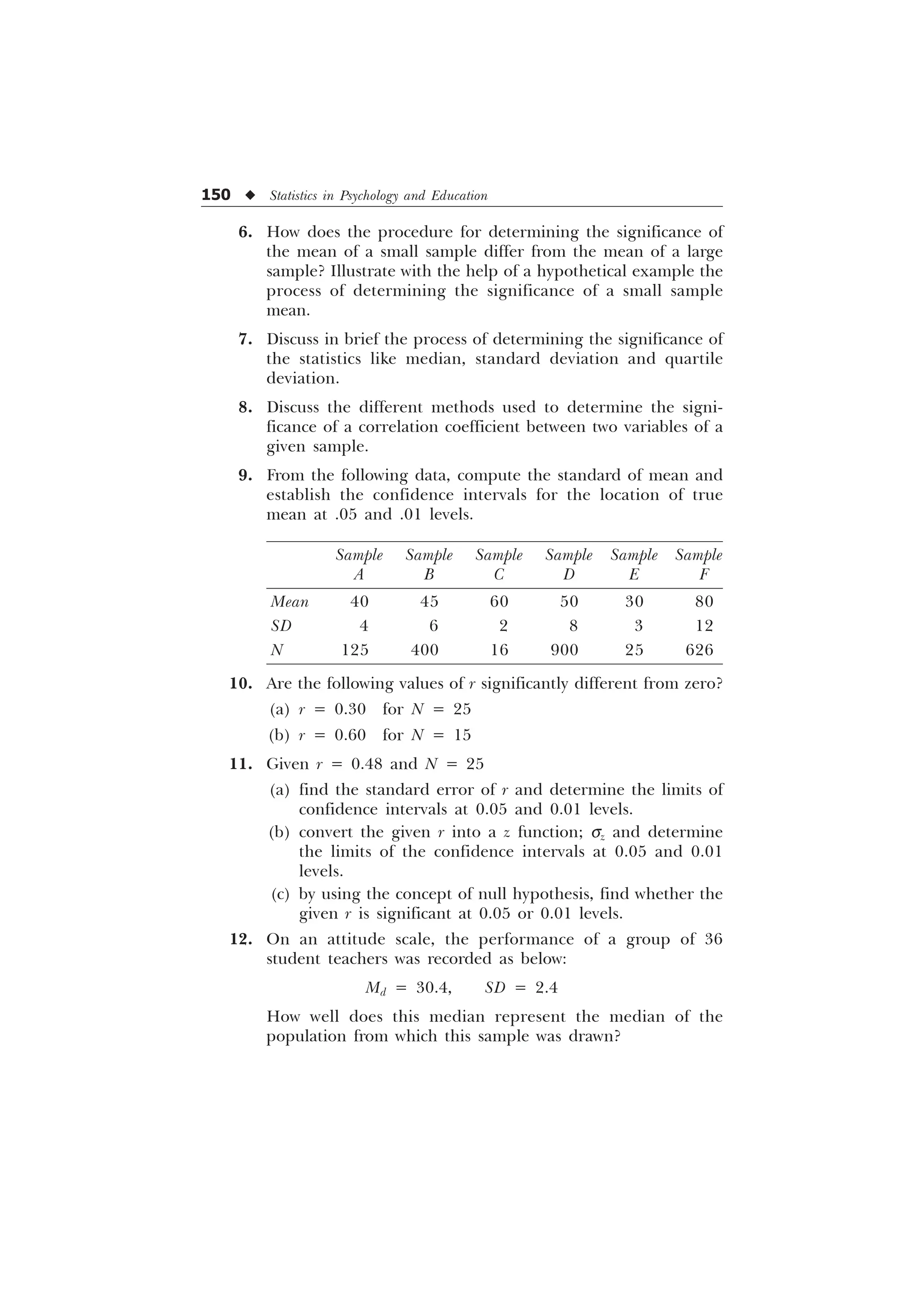

5 students, then the marks obtained by the 3rd student from either

side will be termed as the median of the scores of the group of students

under consideration.

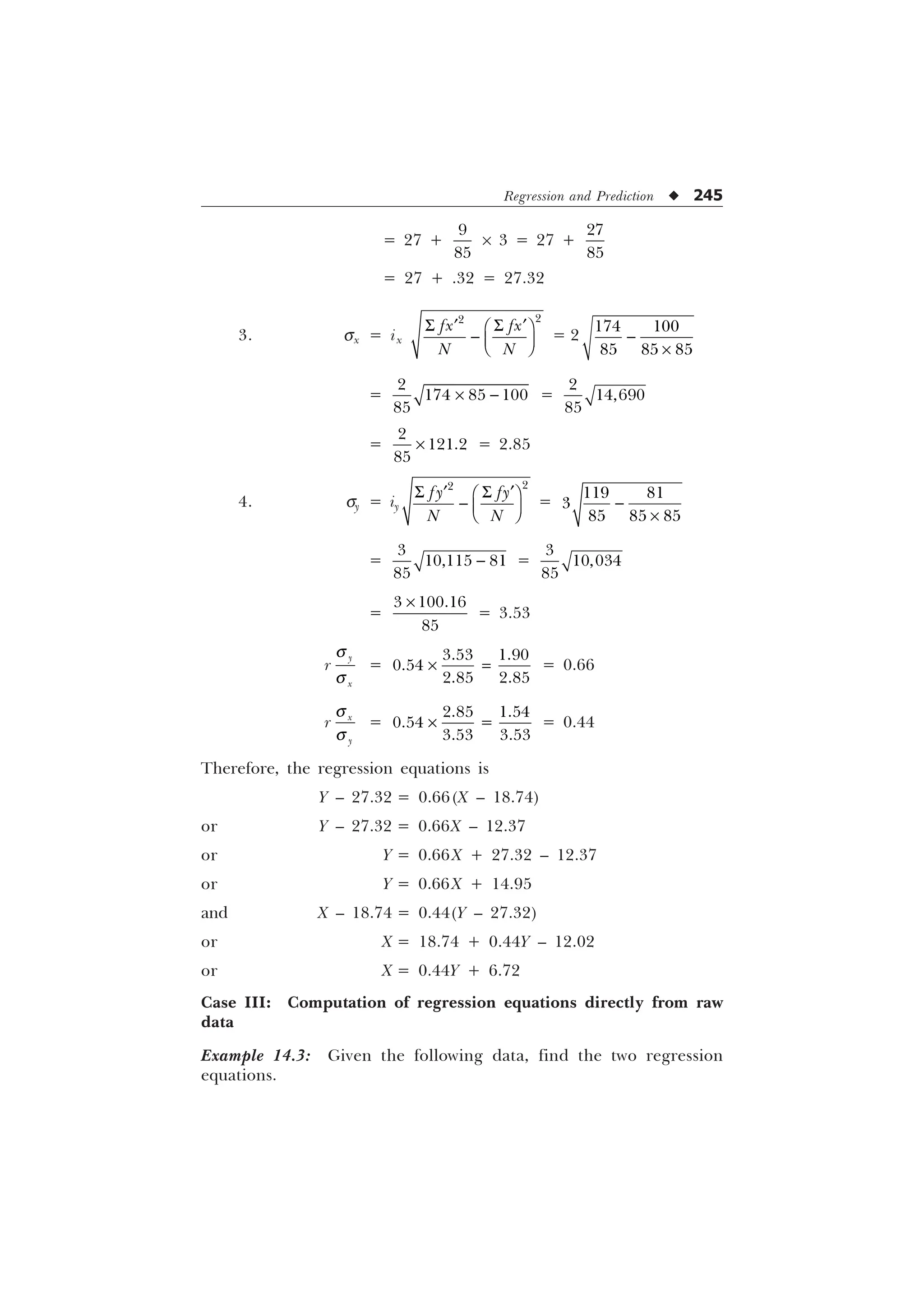

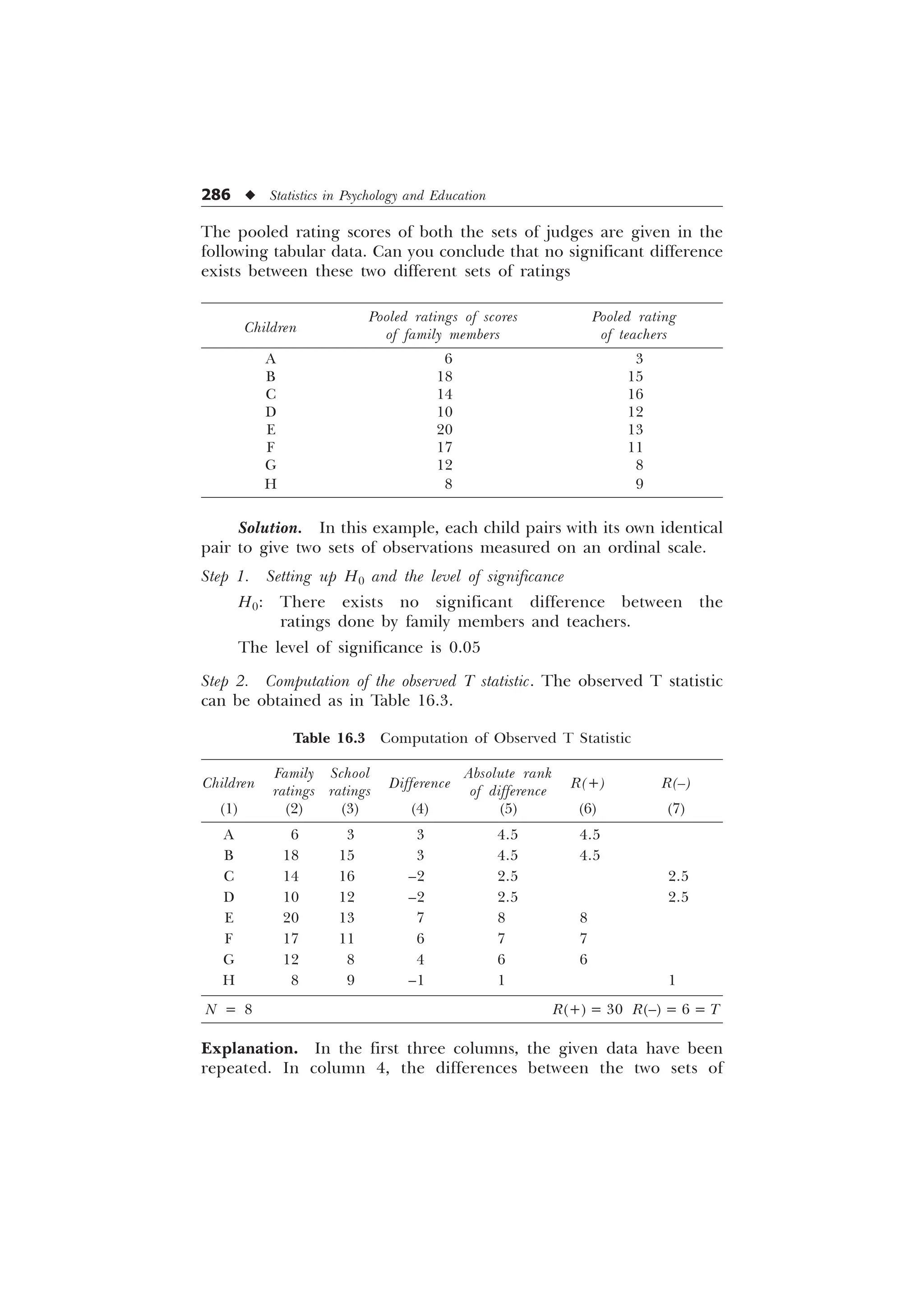

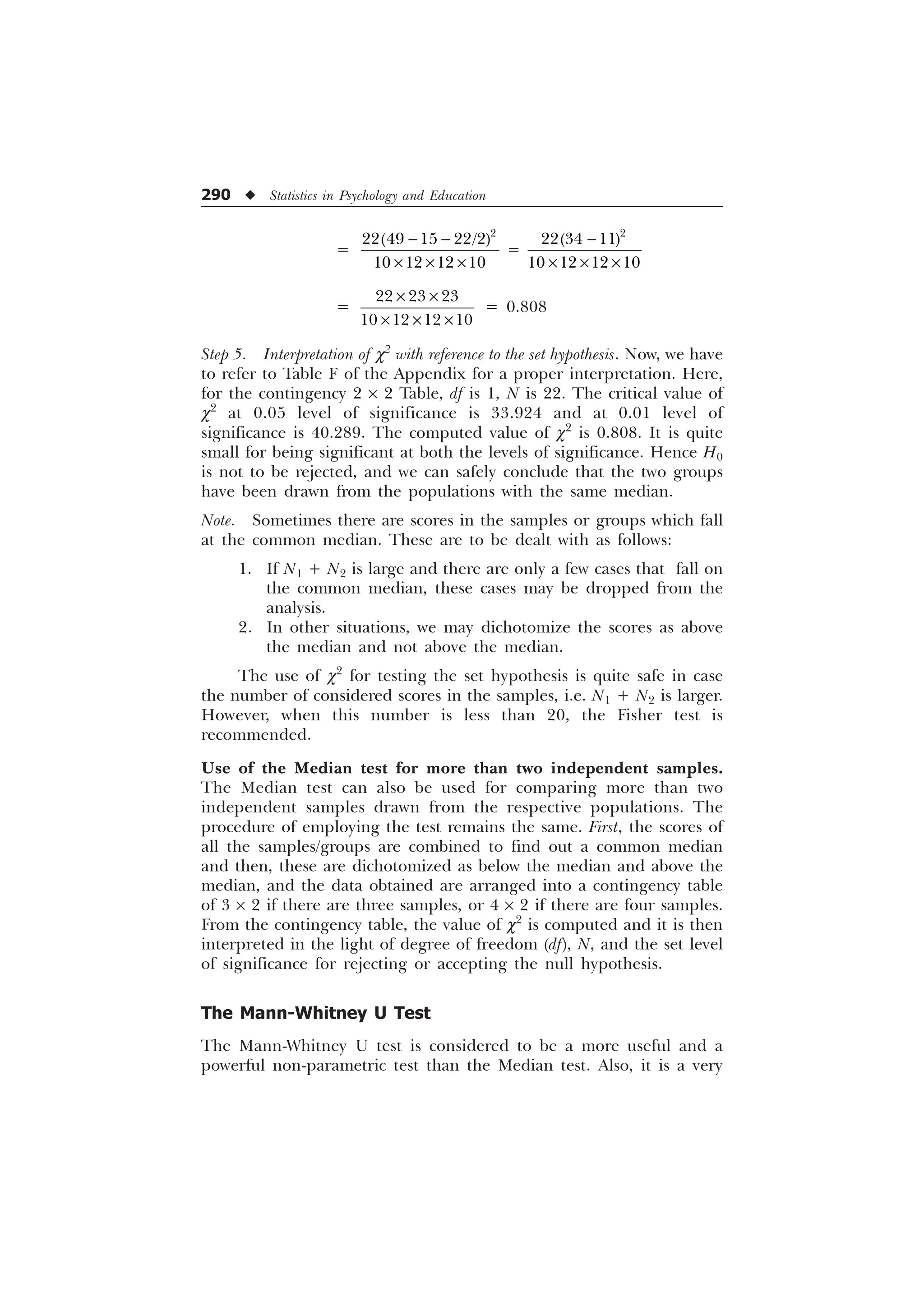

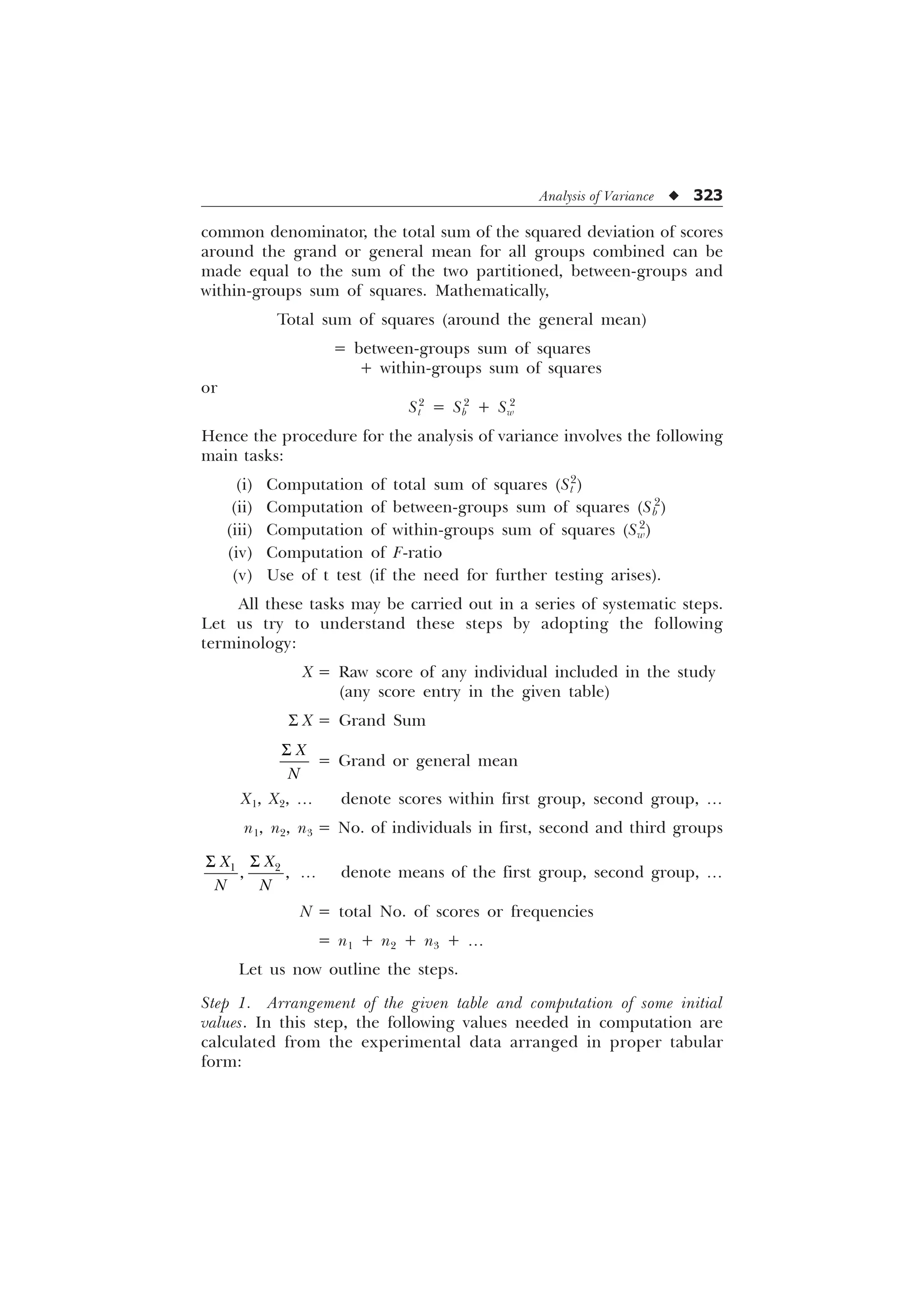

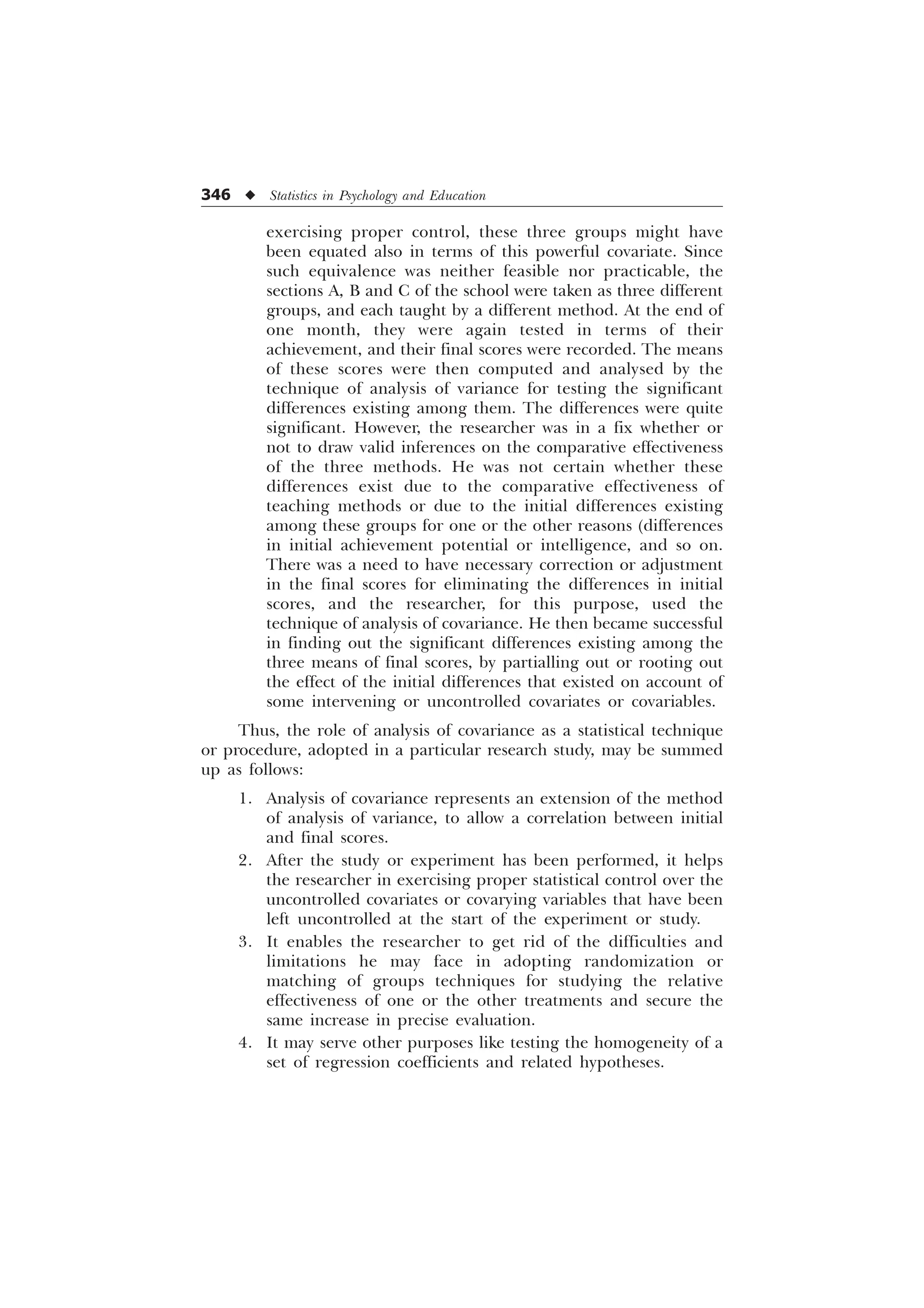

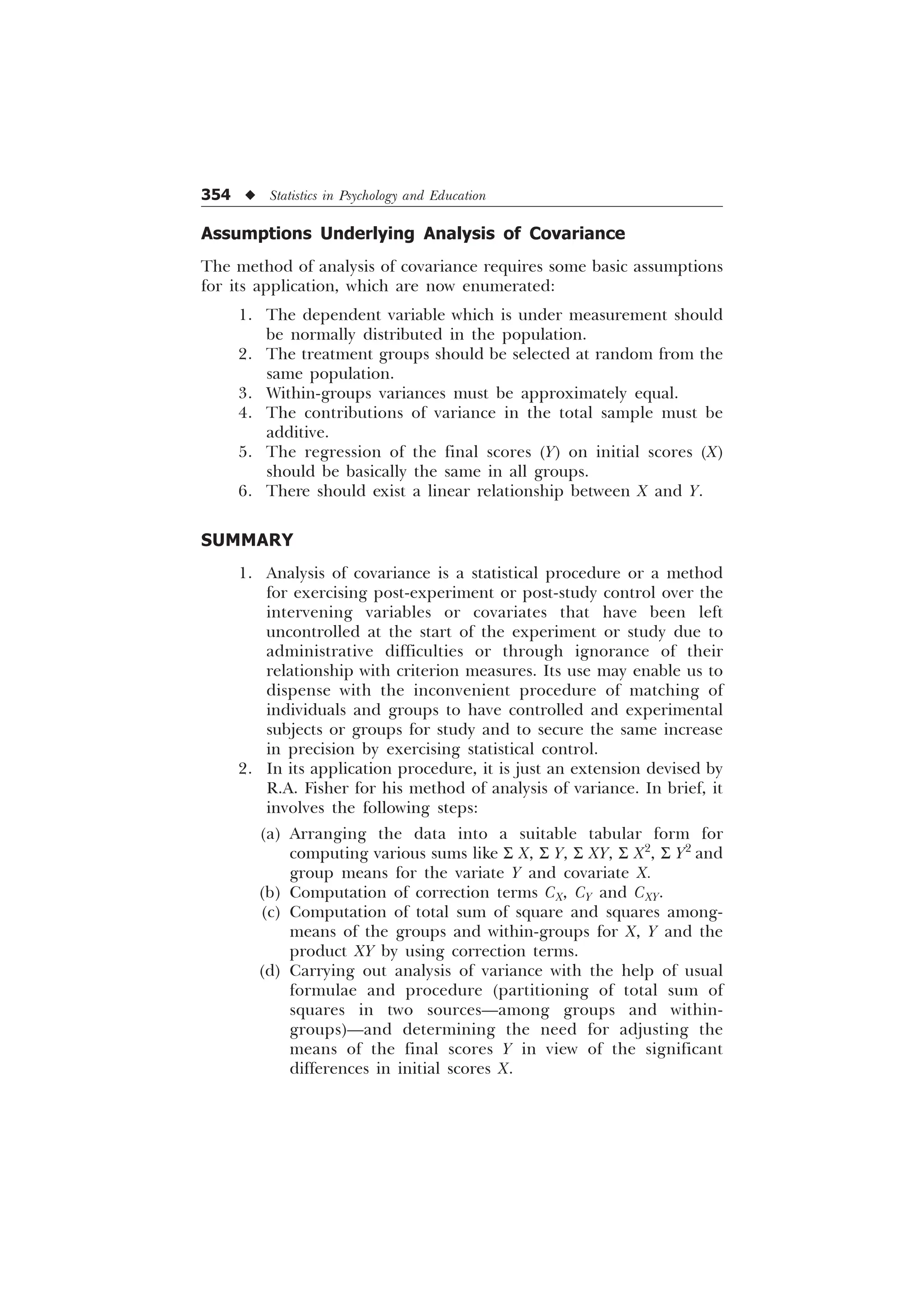

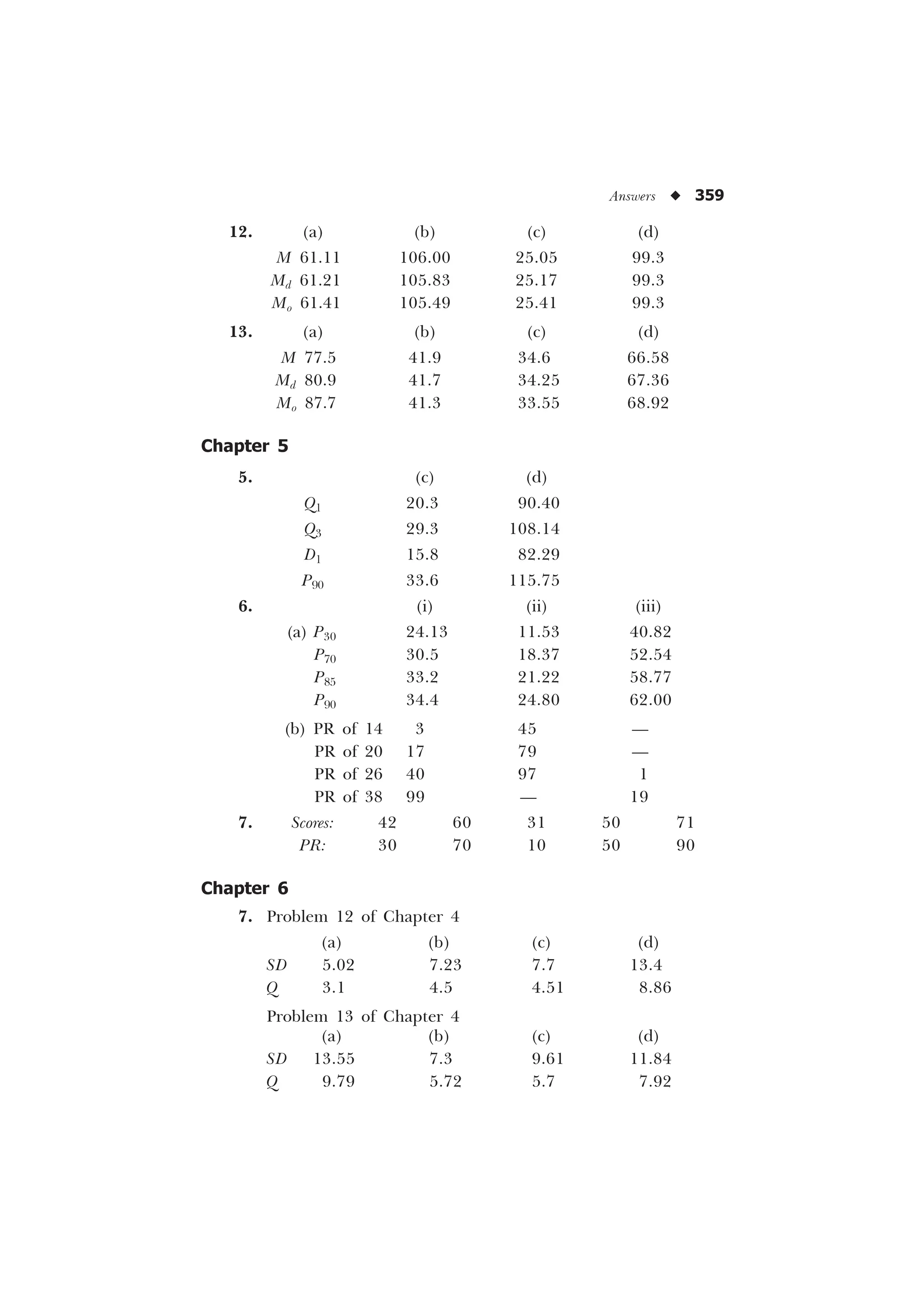

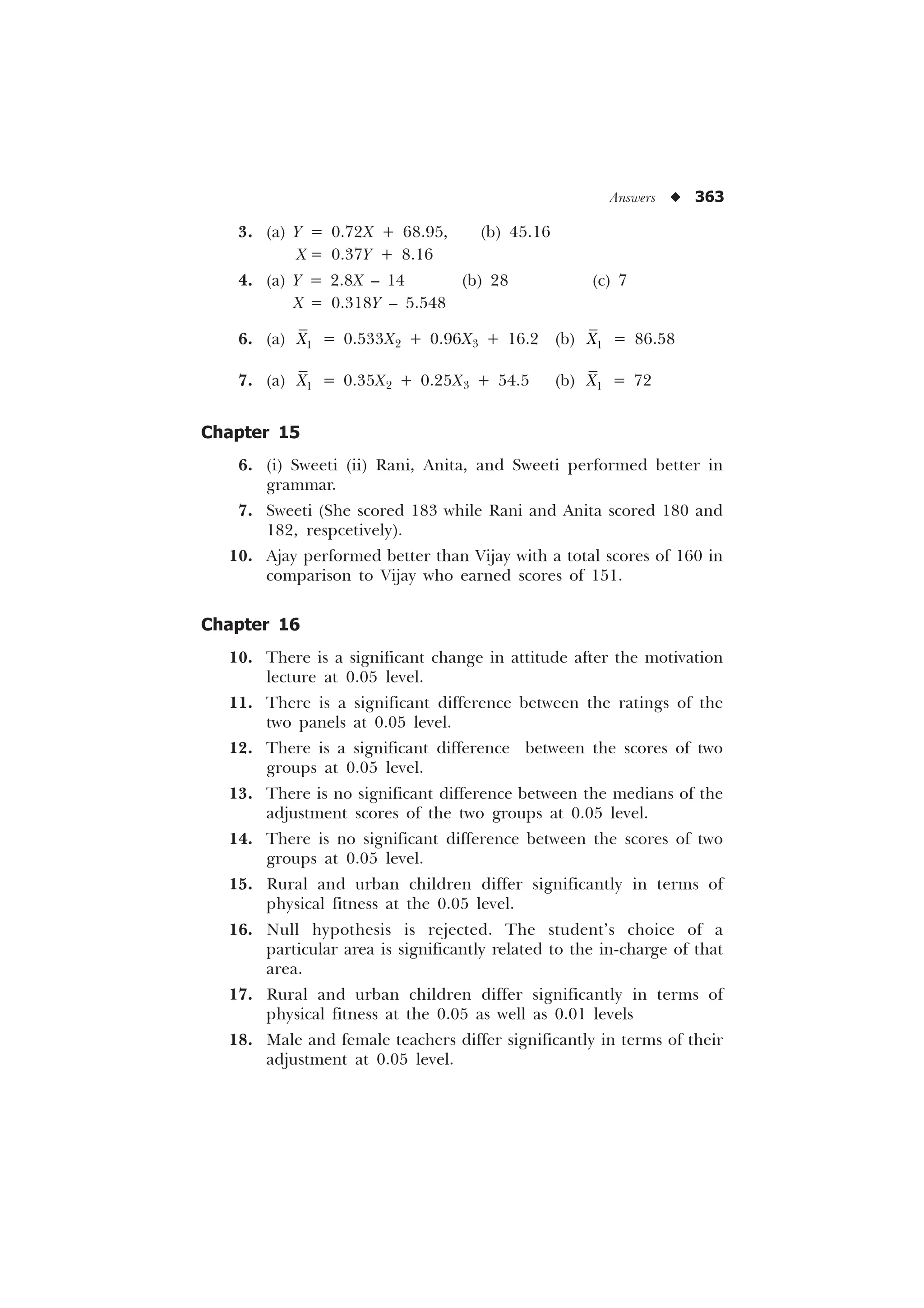

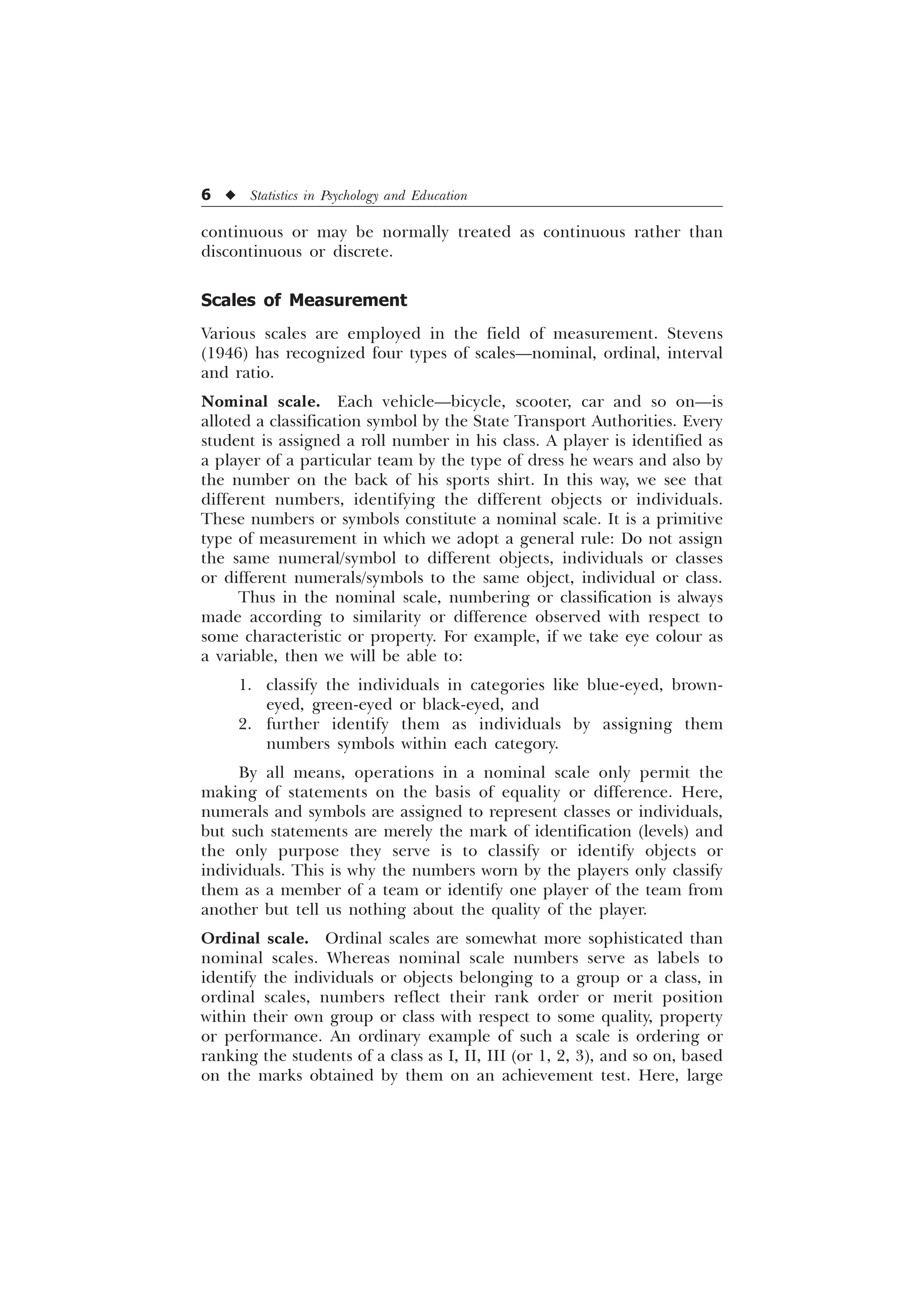

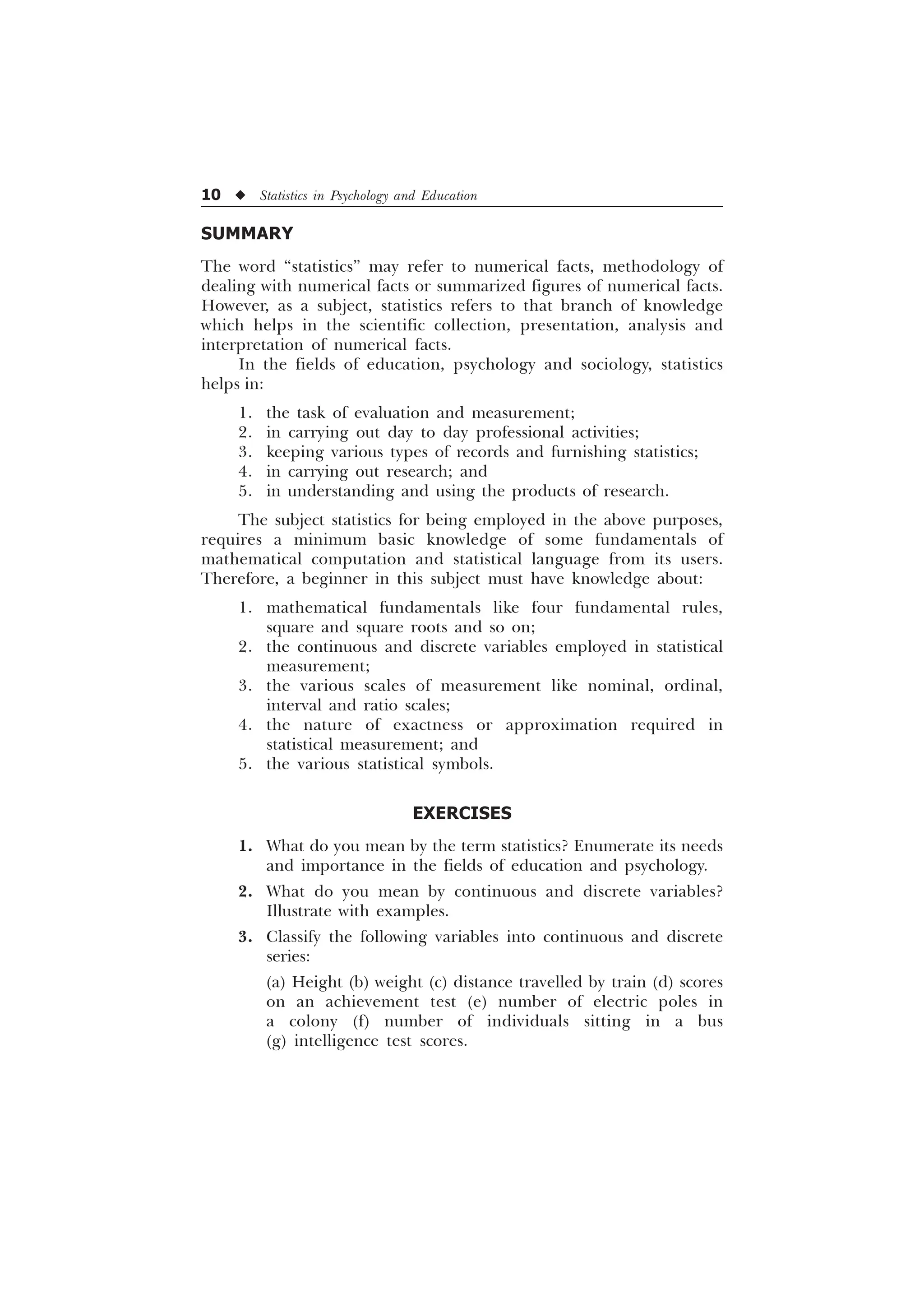

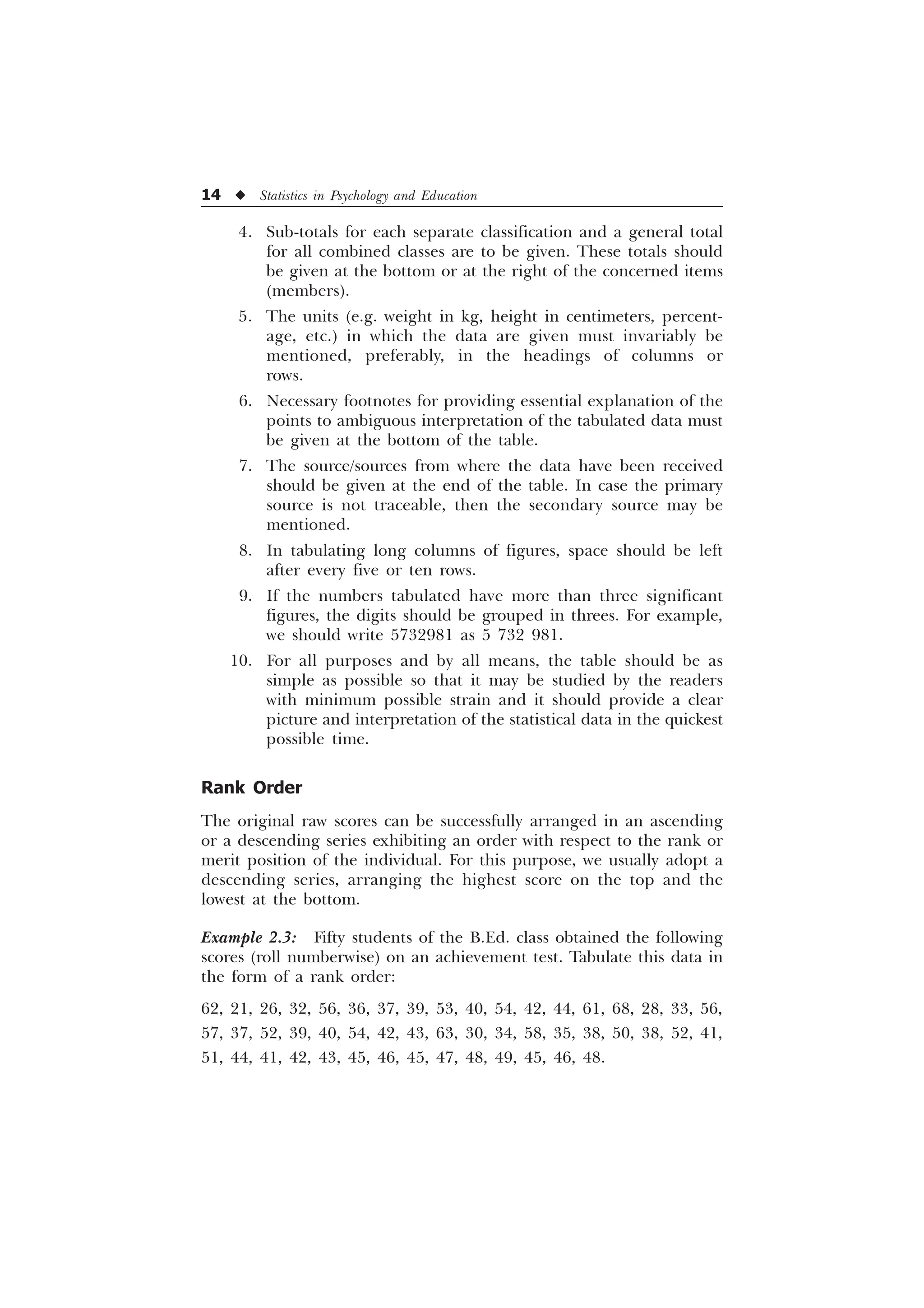

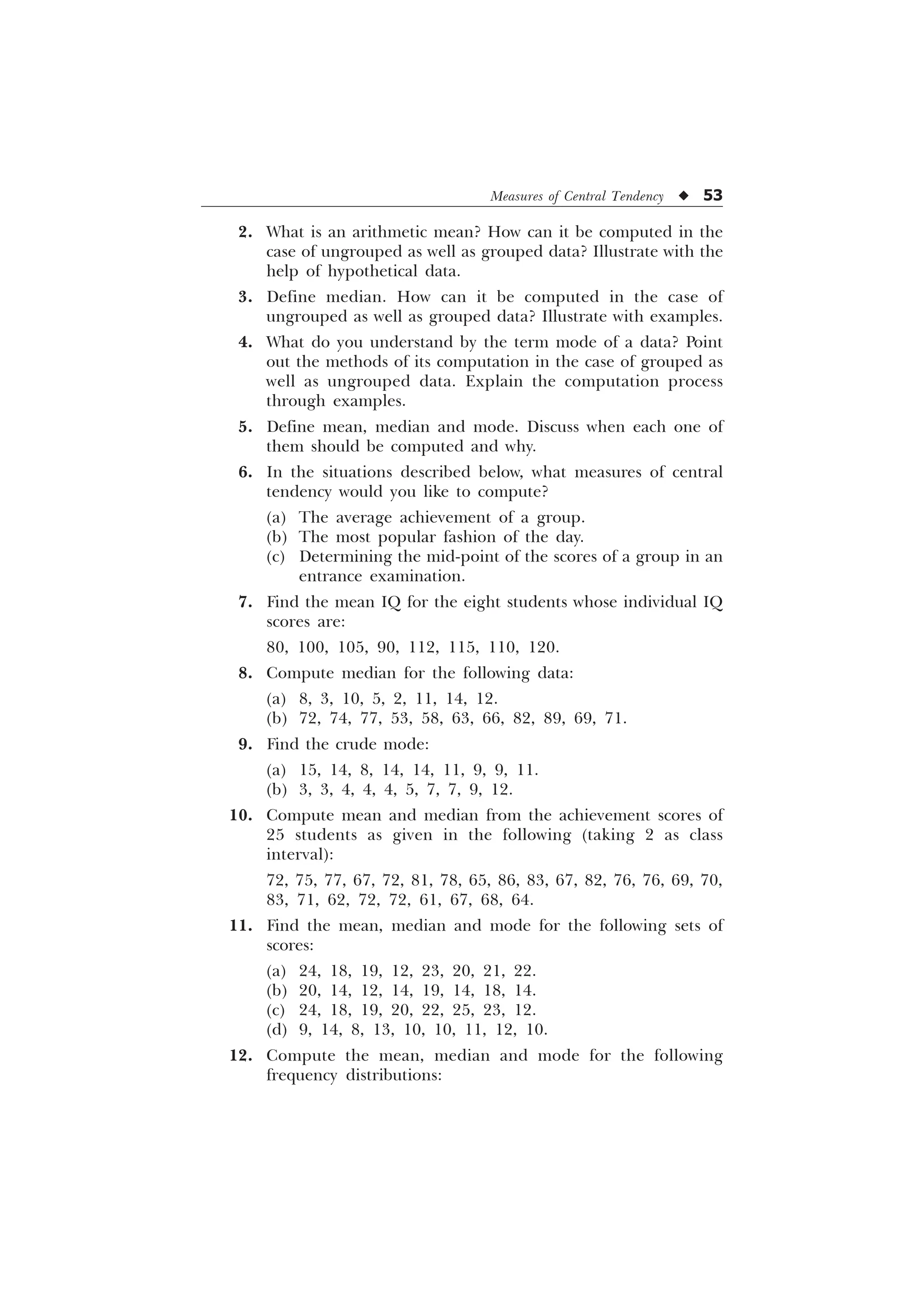

Computation of median for ungrouped data. The following two

situations could arise:

1. When N (No. of items in a series) is odd. In this case where N,

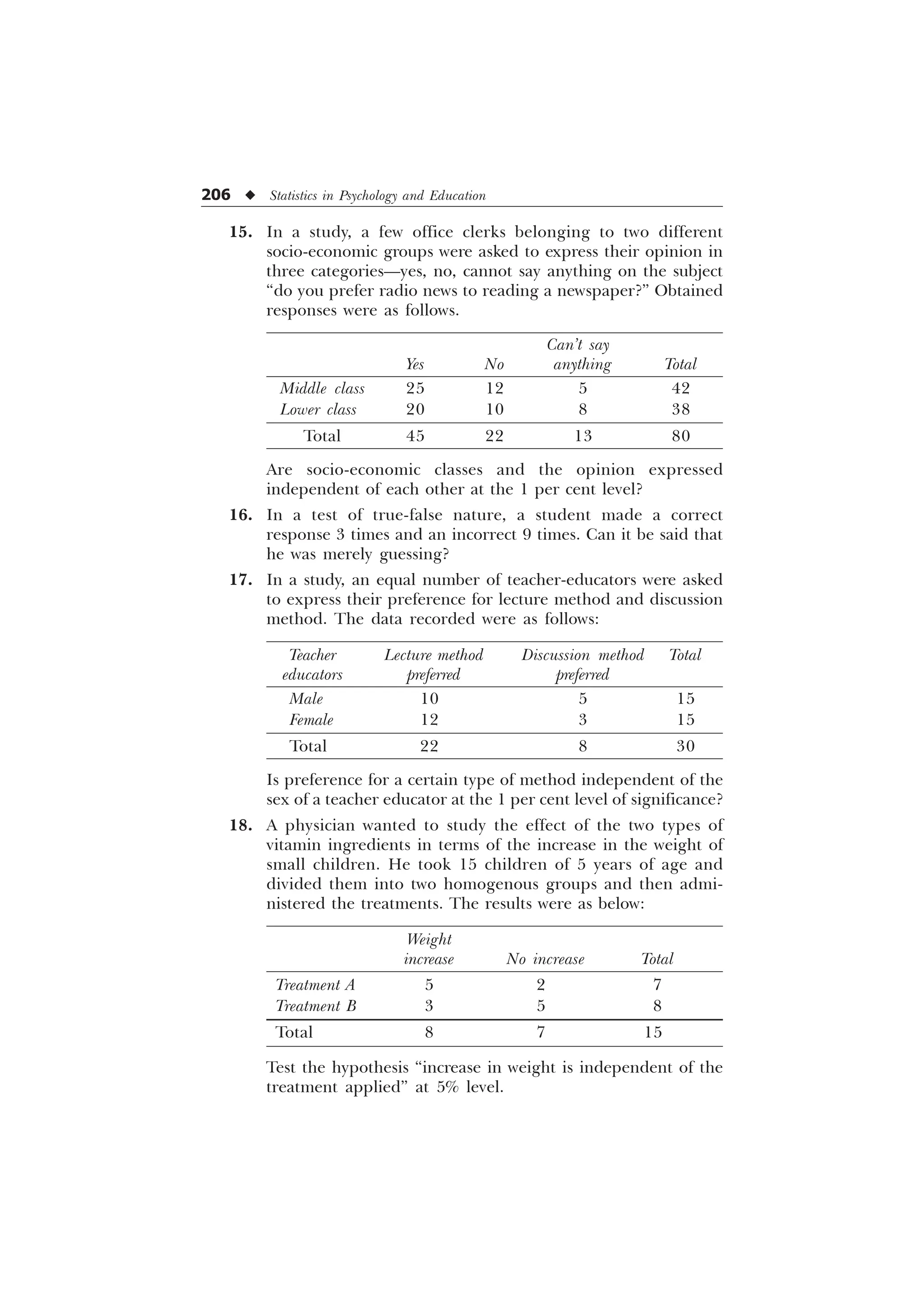

is odd (not divisible by 2), the median can be computed by the

formula Md = the measure or value of the (N +1)/2-th item.

Example 4.3: Let the scores obtained by 7 students on an

achievement test be 17, 47, 15, 35, 25, 39, 44. Then, first of all, for

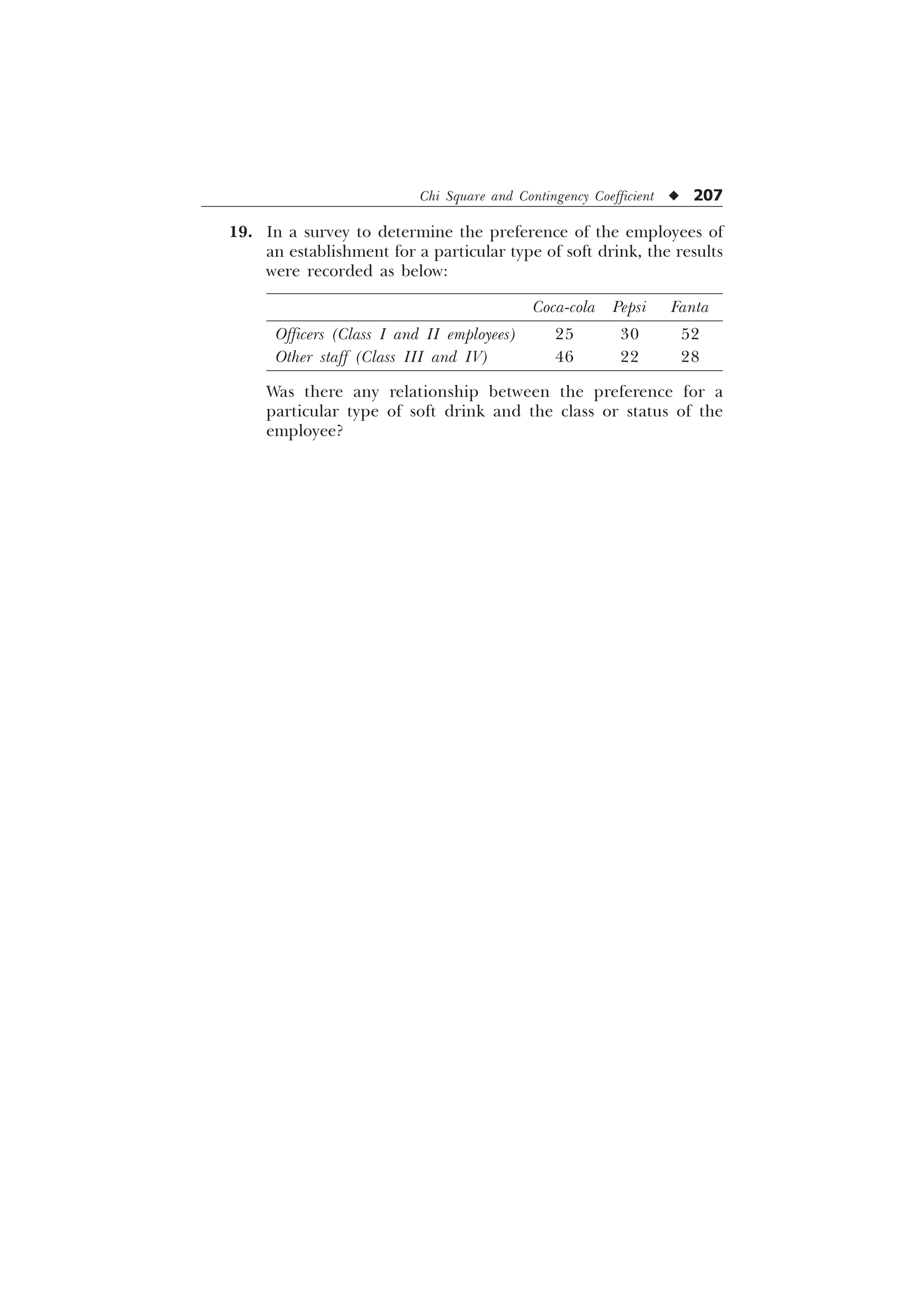

calculating median, we have to arrange the scores in ascending or

descending order: 15, 17, 25, 35, 39, 44, 47. Here N (= 7) is odd, and

therefore, the score of the (N + 1)/2-th item or 4th student, i.e. 35

will be the median of the given scores.

2. When N (No. of items in a series) is even. In the case where N

is even (divisible by 2), the median is determined by the

following formula:

WKH YDOXH RI WK LWHP WKH YDOXH RI @WK LWHP

G

1 1

0

Example 4.4: Let there be a group of 8 students whose scores in a test

are, 17, 47, 15, 35, 25, 39, 50, 44. For calculating mean of these scores

we proceed as follows:

Arrangement of scores in ascending series: 15, 17, 25, 35, 39,

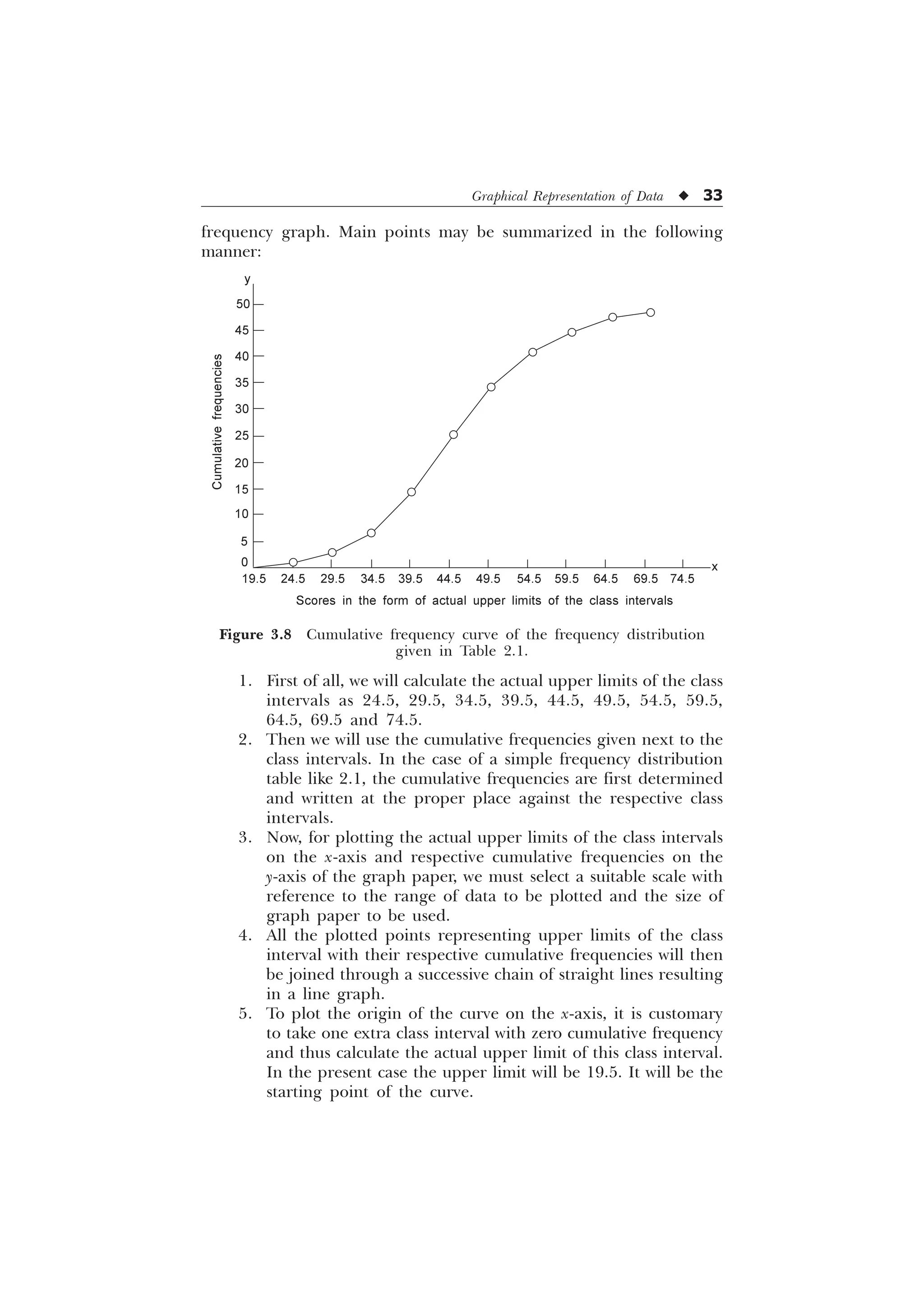

44, 47, 50

The score of the (N/2)th, i.e. 4th student = 35

The score of the [(N/2) + 1]th, i.e. 5th student = 39

Then,

Median =

= 37

Computation of median for grouped data (in the form of frequency

distribution). If the data is available in the form of a frequency

distribution like below, then calculation of median first requires the

location of median class.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/stats-s-241206101830-e3d4cc67/75/Stats-S-K-Mangal-statistics-textook-in-pdf-56-2048.jpg)

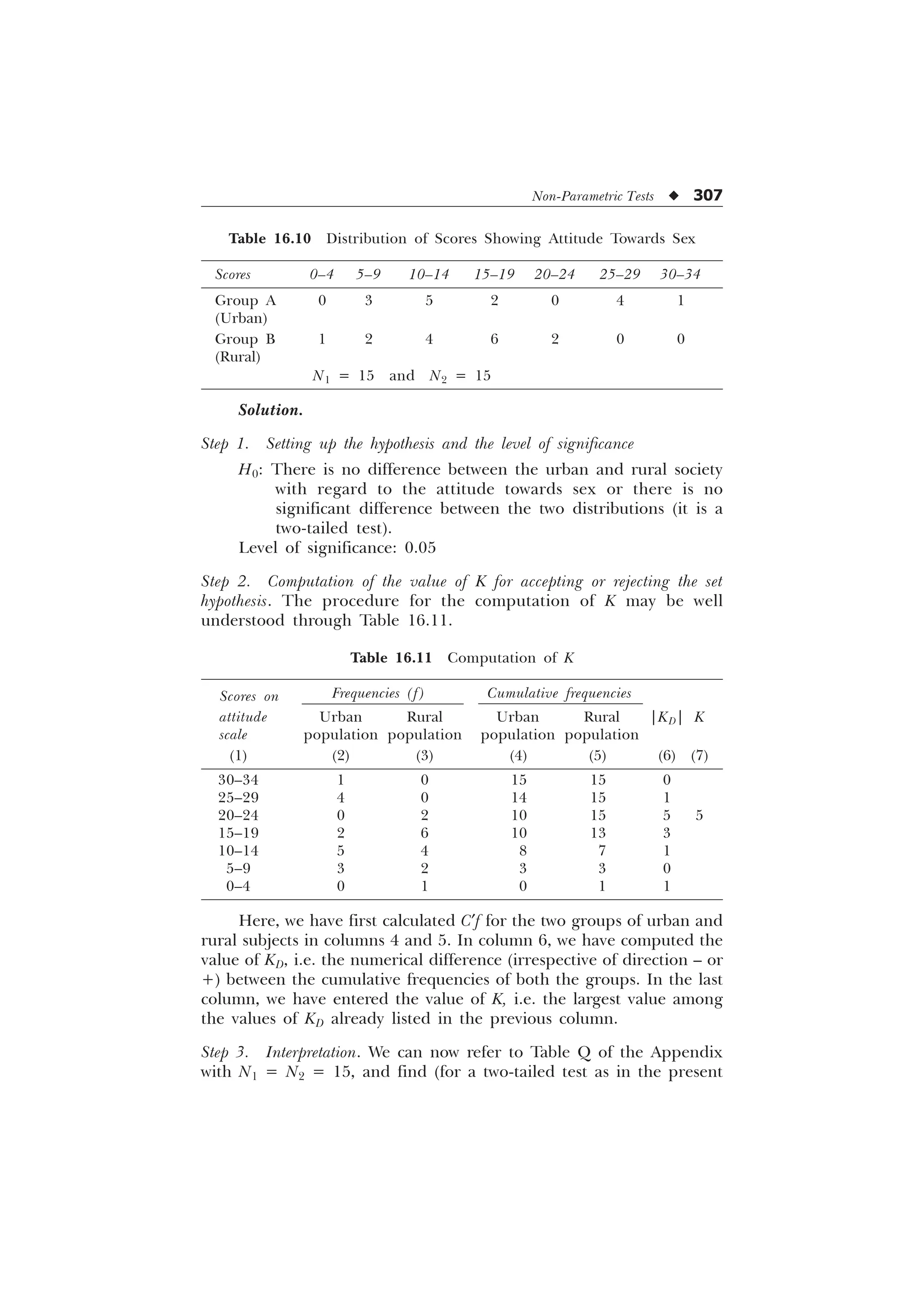

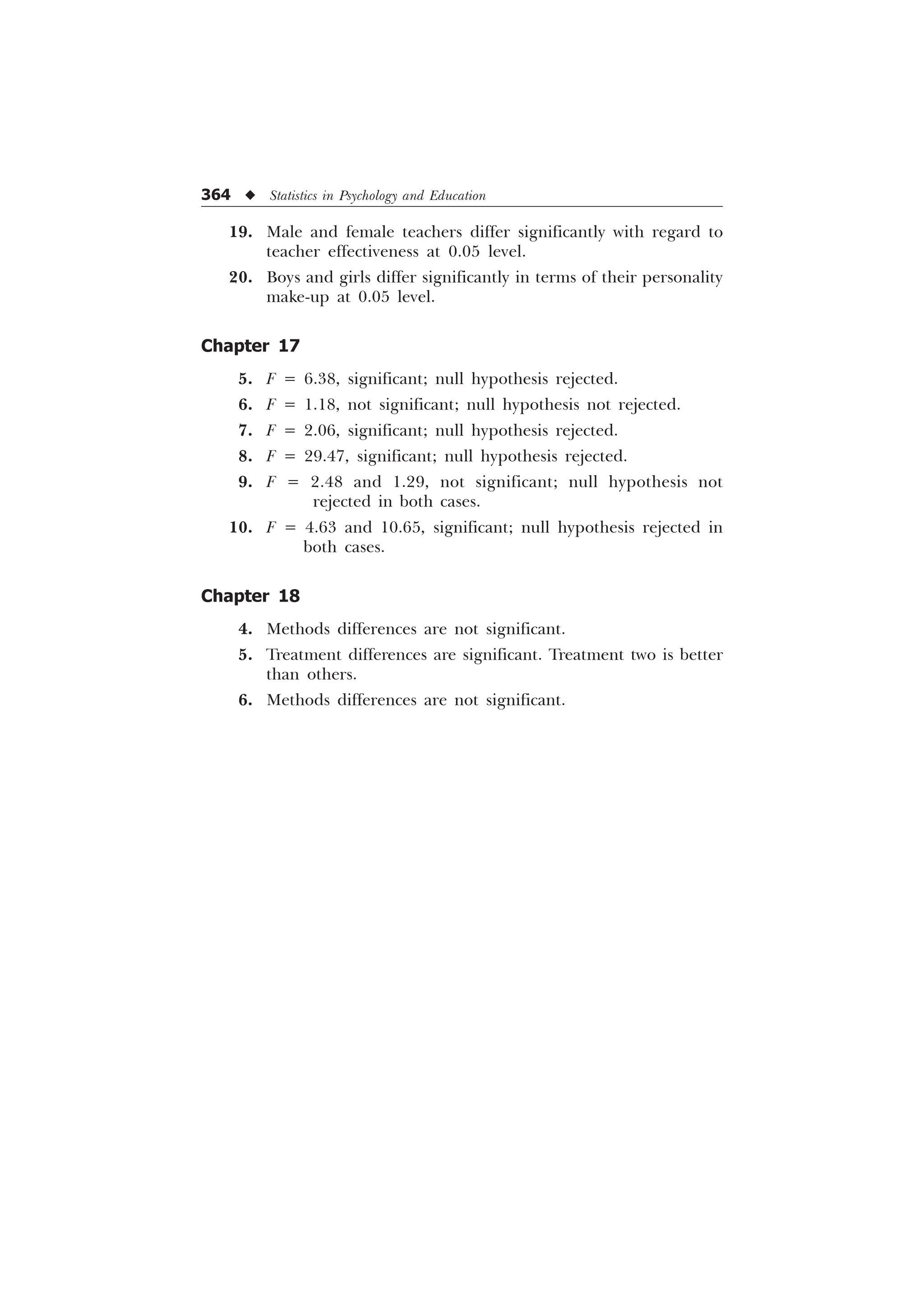

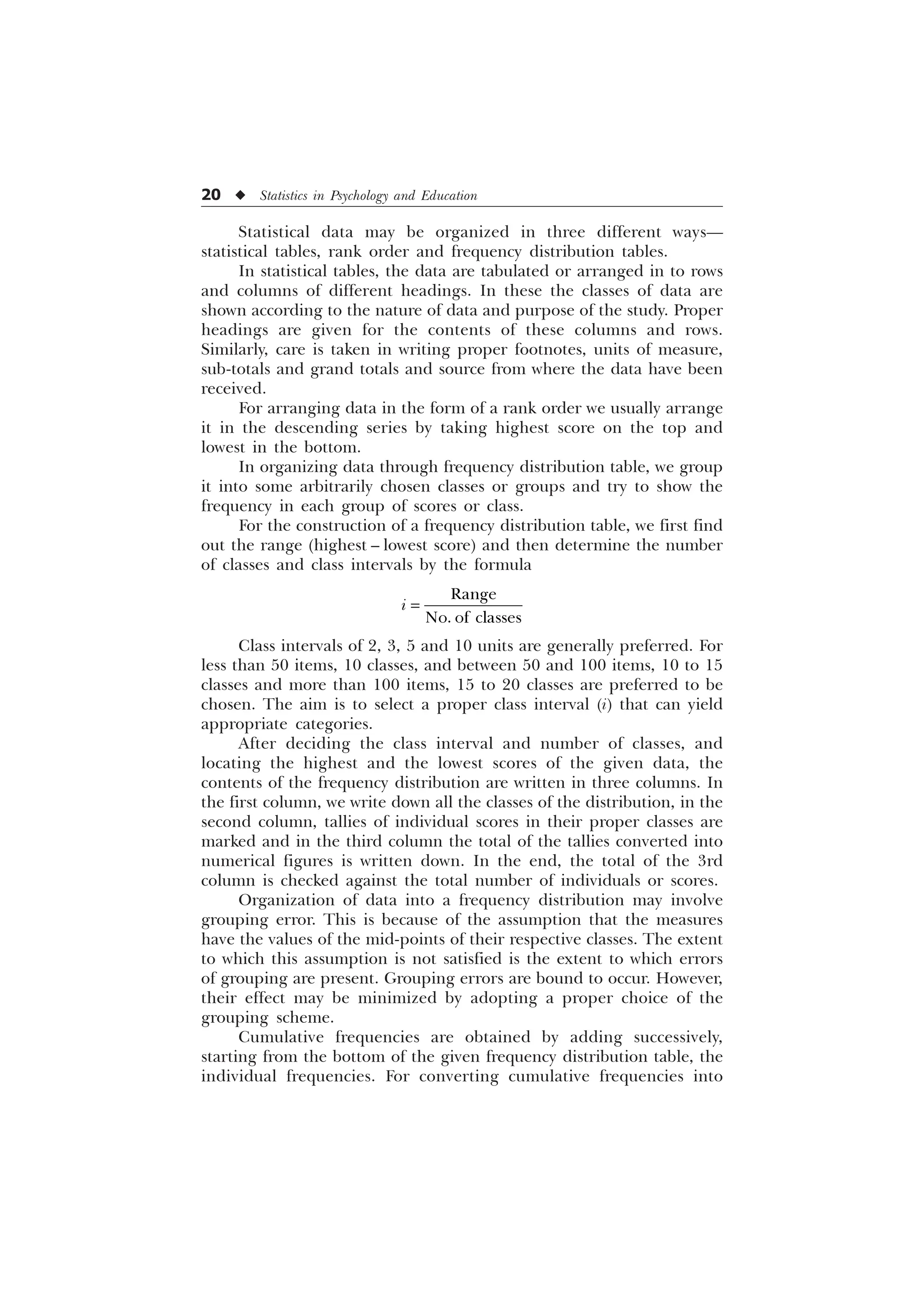

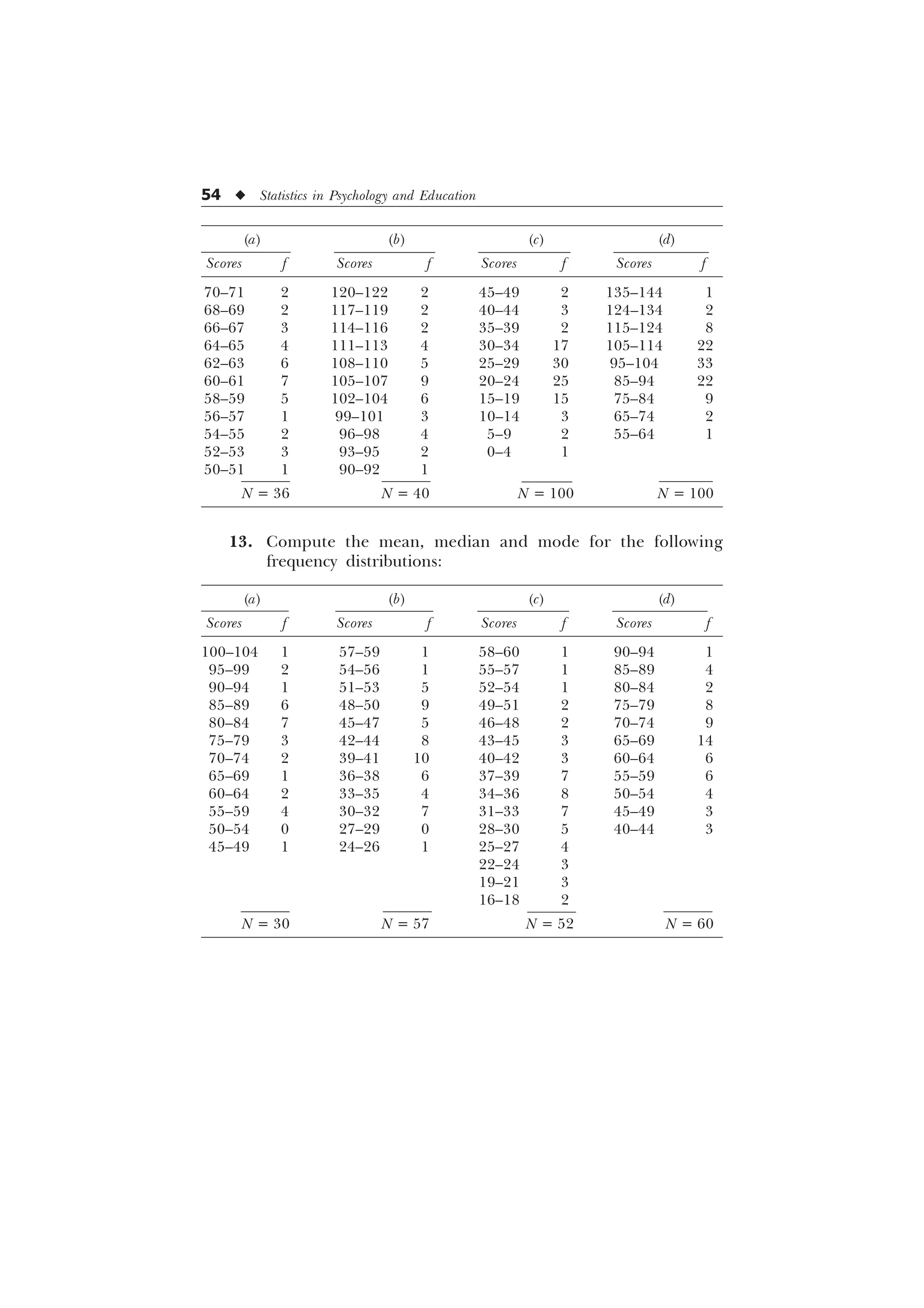

![Measures of Central Tendency u 51

2. Mode is that value of the item which occurs most frequently

or is repeated maximum number of times in a given series.

Therefore, when we need to know the most often recurring

score or value of the item in a series, we compute mode. On

account of this characteristic, mode has unique importance in

the large scale manufacturing of consumer goods. In finding

the sizes of shoes and readymade garments which fit most men

or women, the manufacturers make use of the average

indicated by mode.

3. Mode can be computed from the histogram and other

frequency curves. Therefore, when we already have a graph-

ical representation of the distribution in the form of such

figures, it is appropriate to compute mode instead of mean.

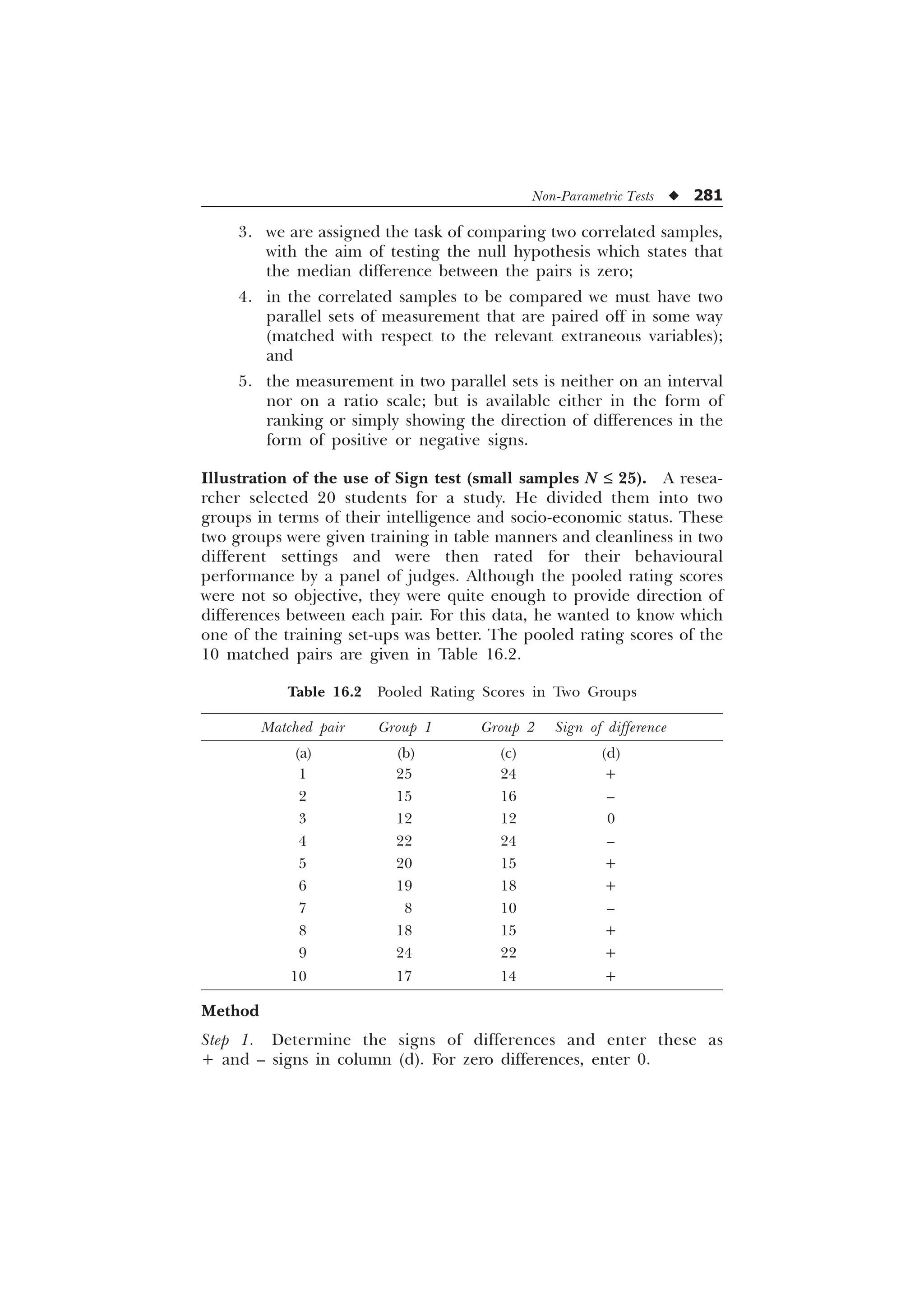

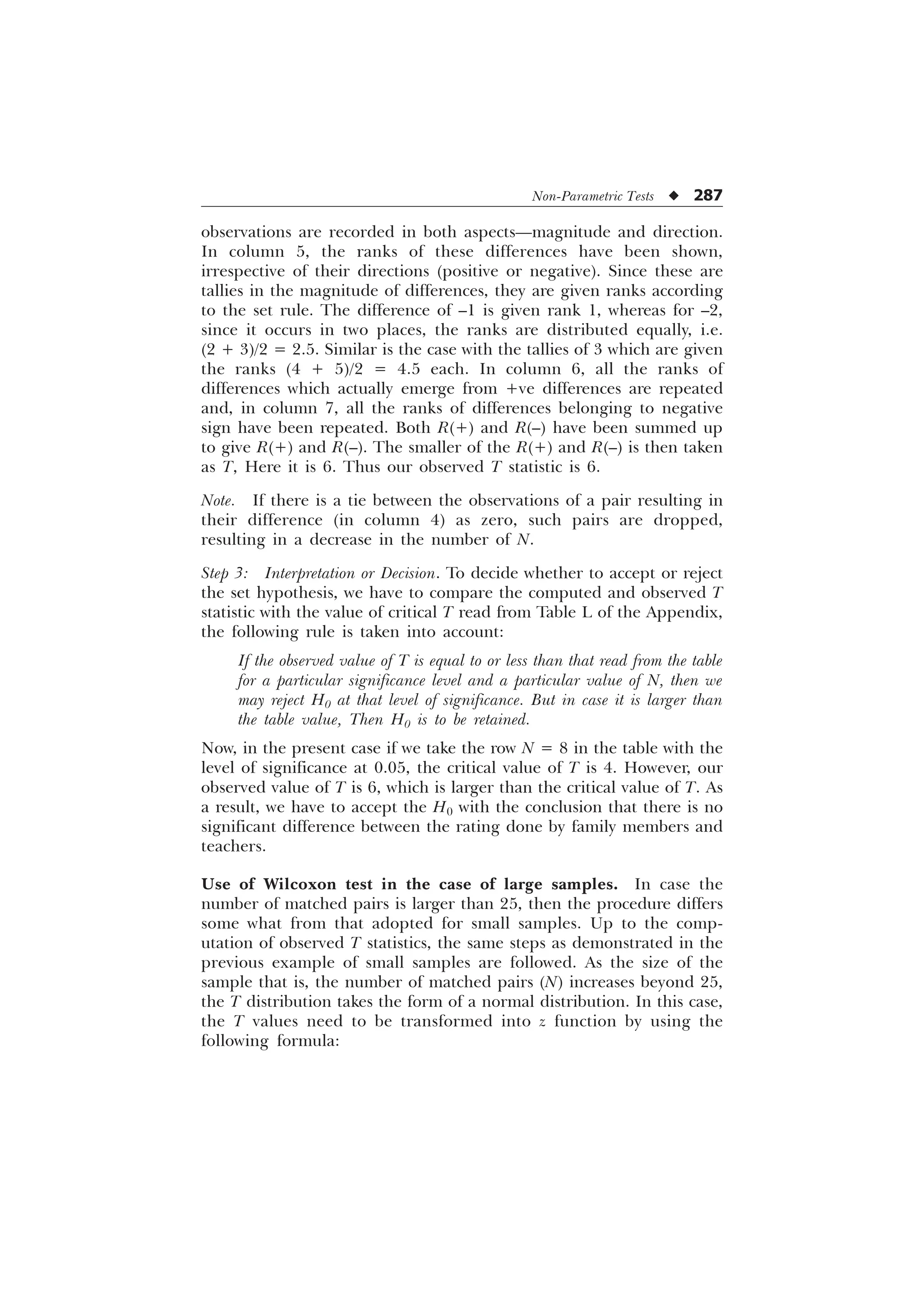

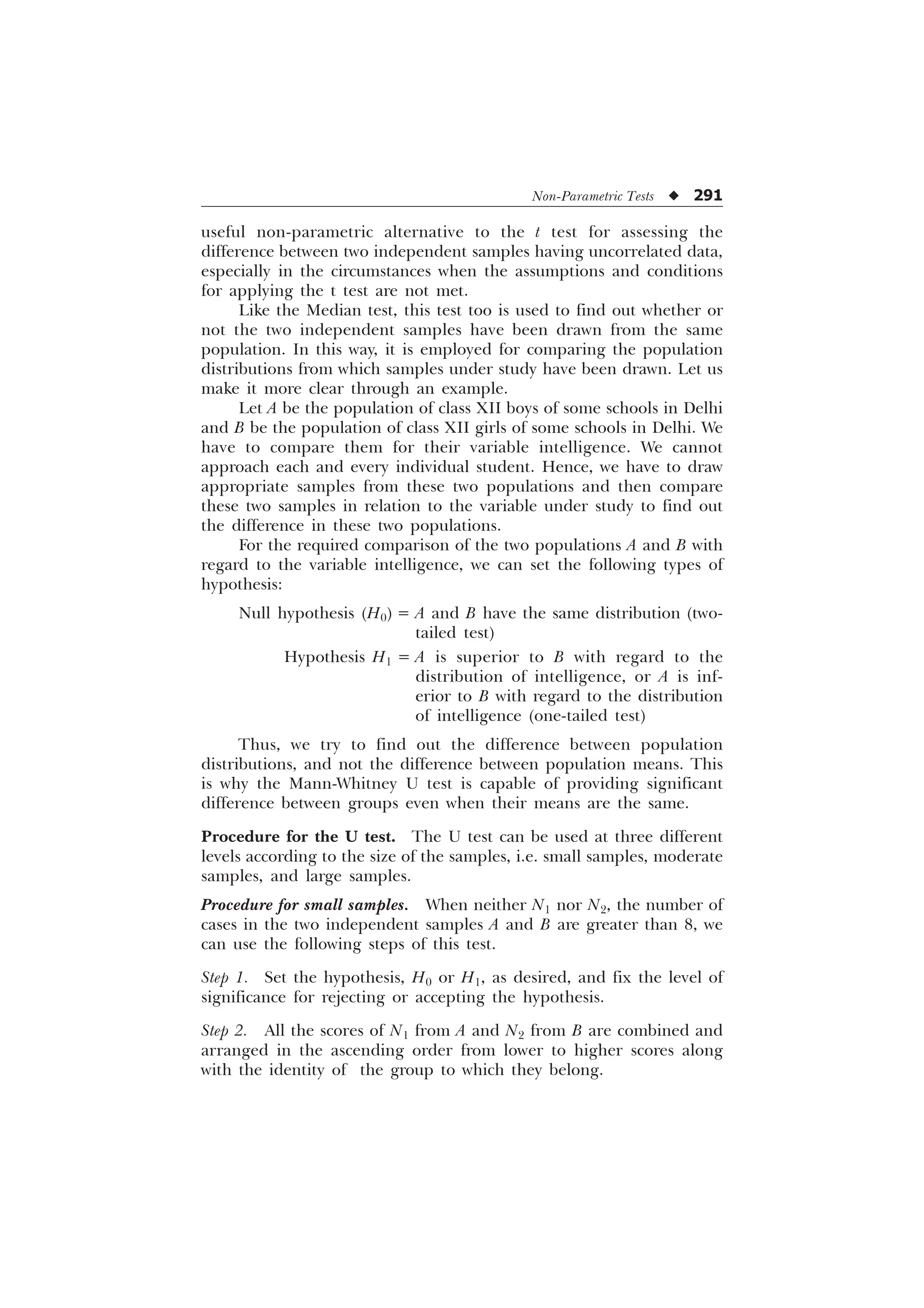

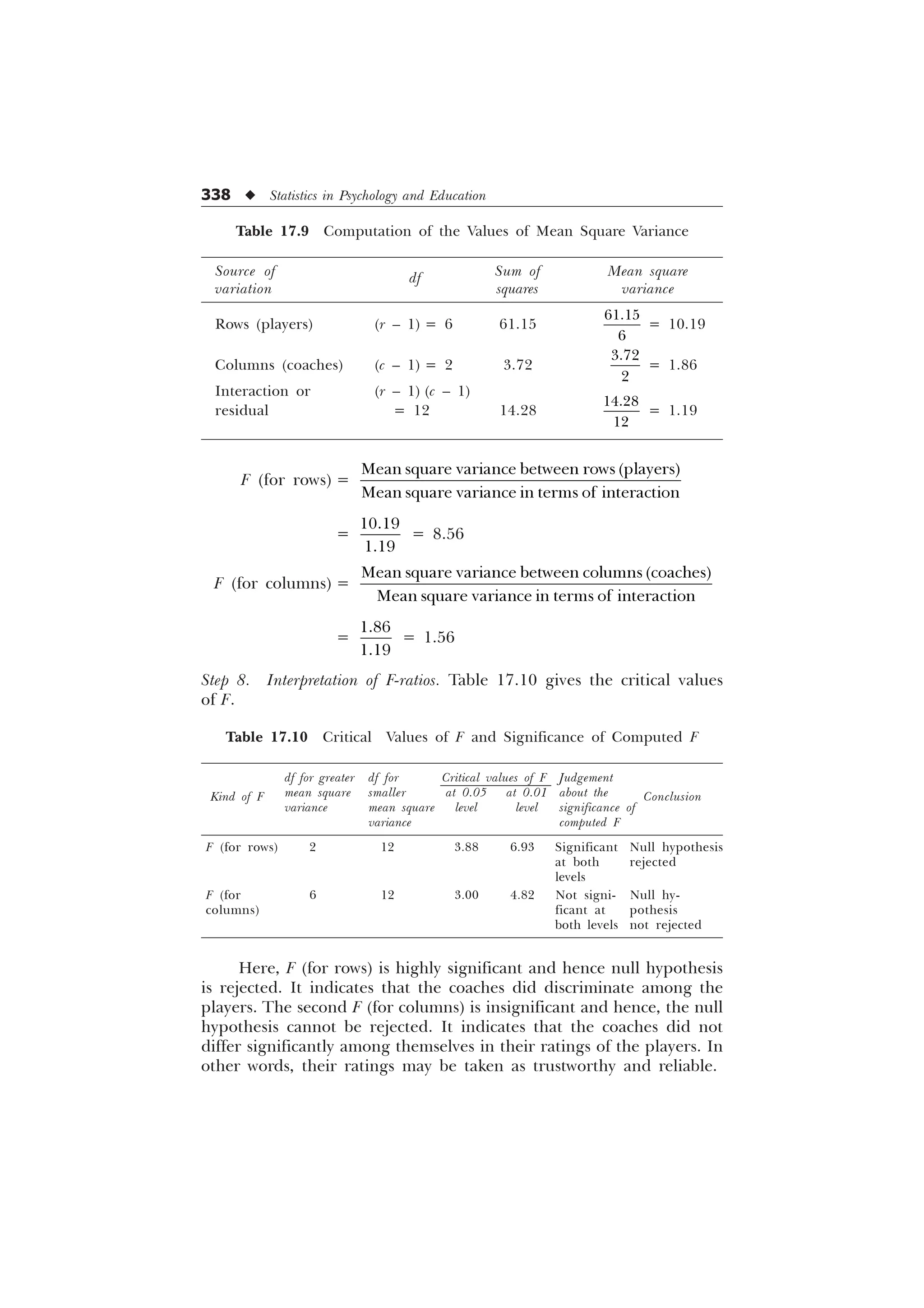

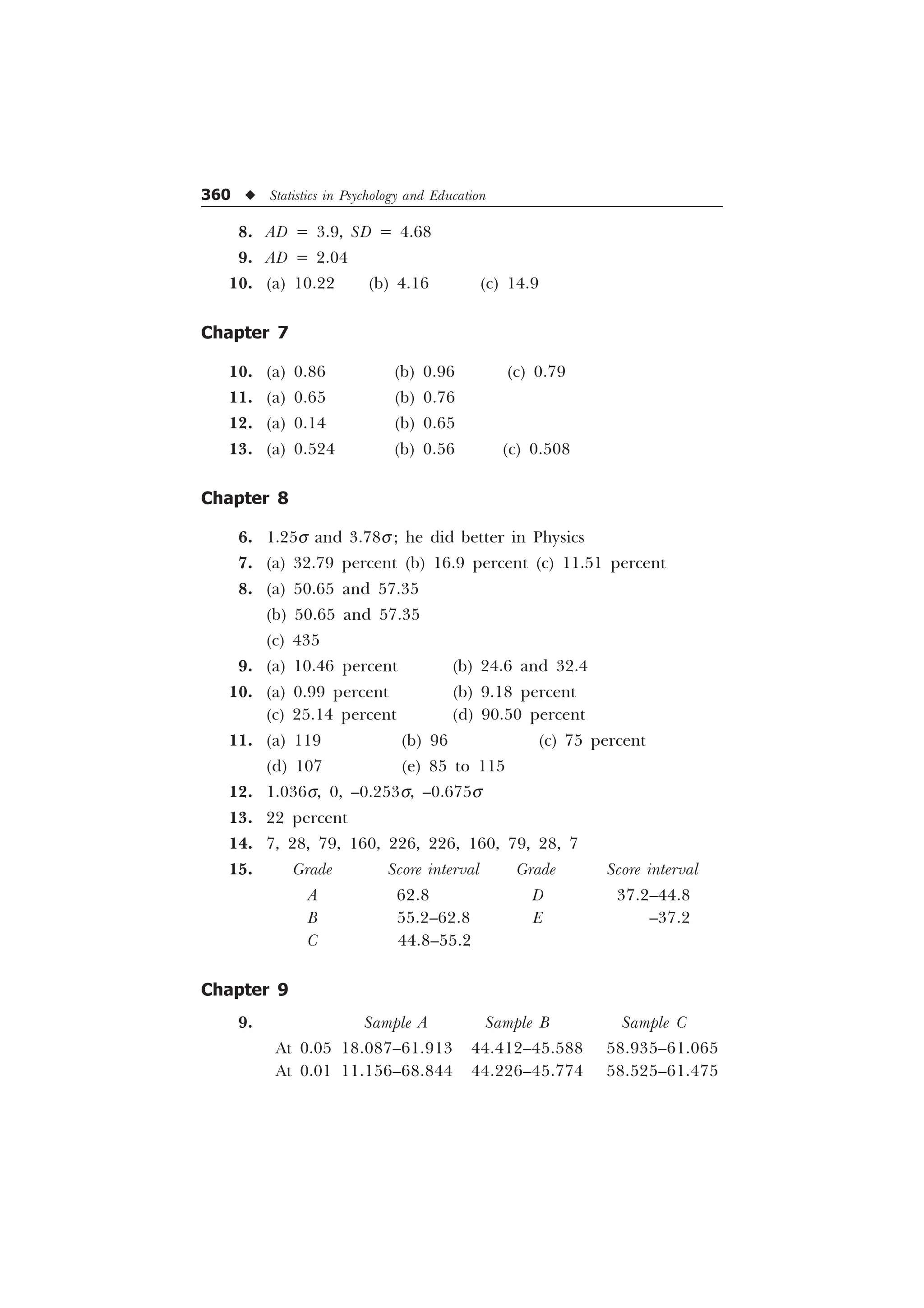

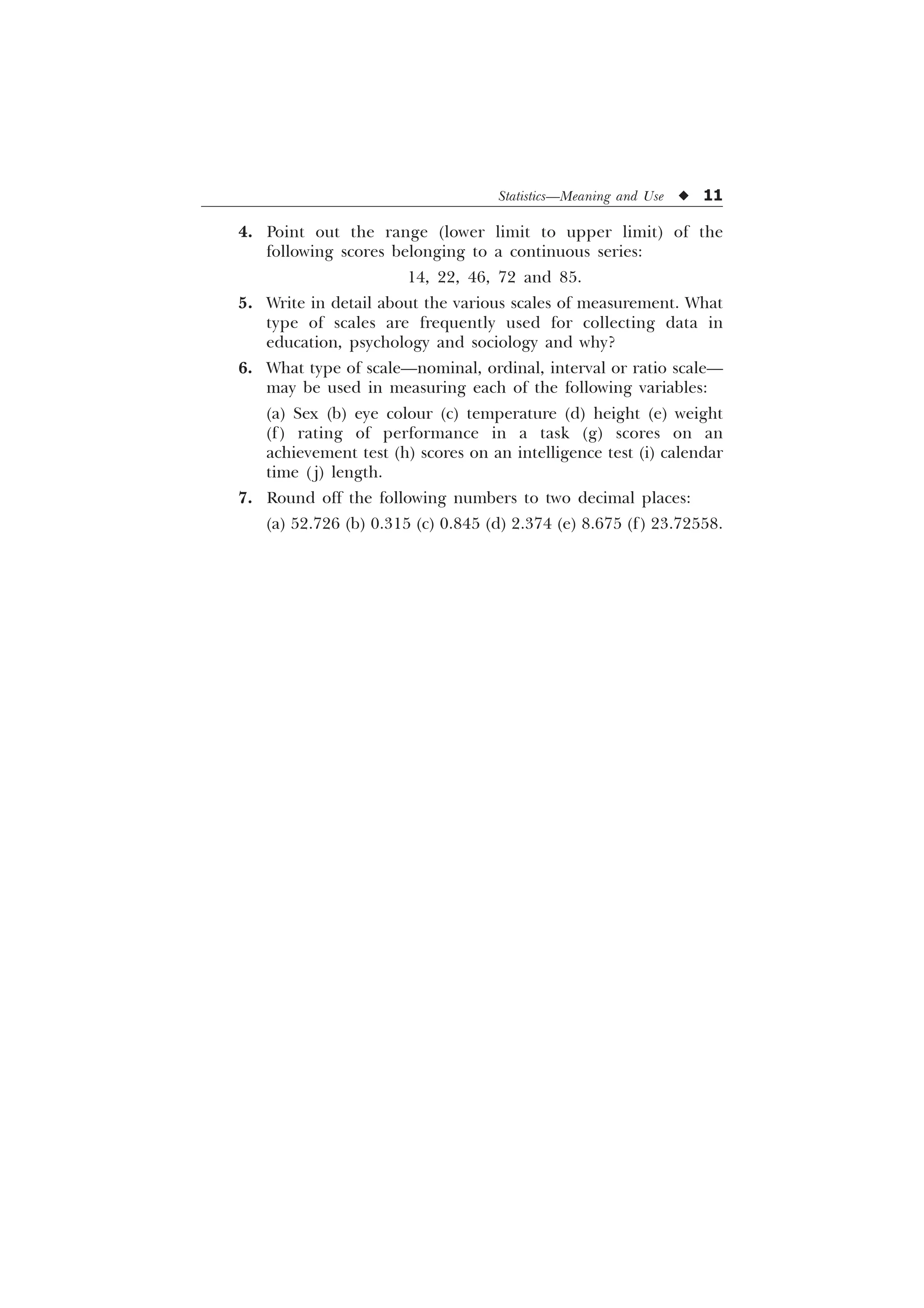

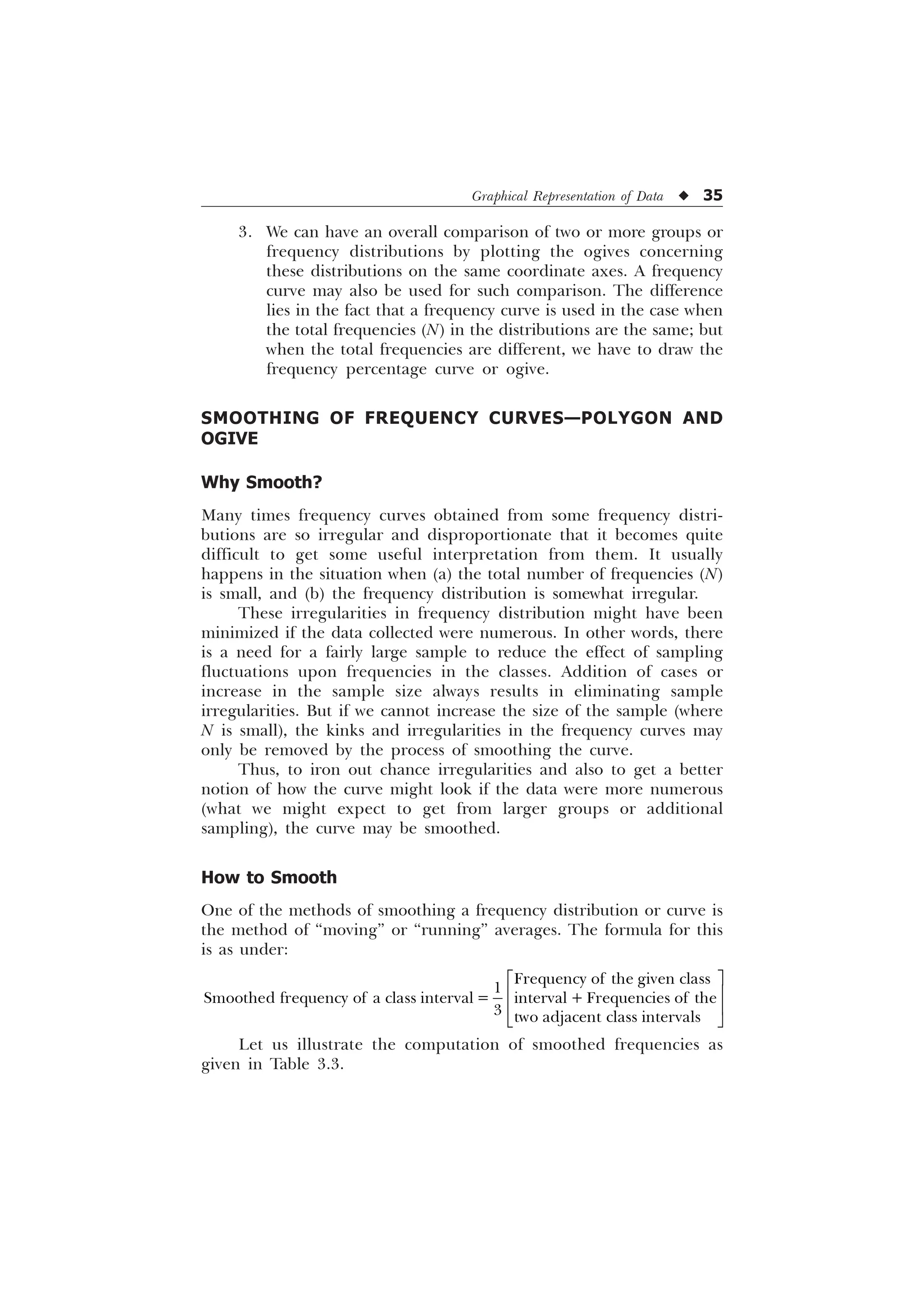

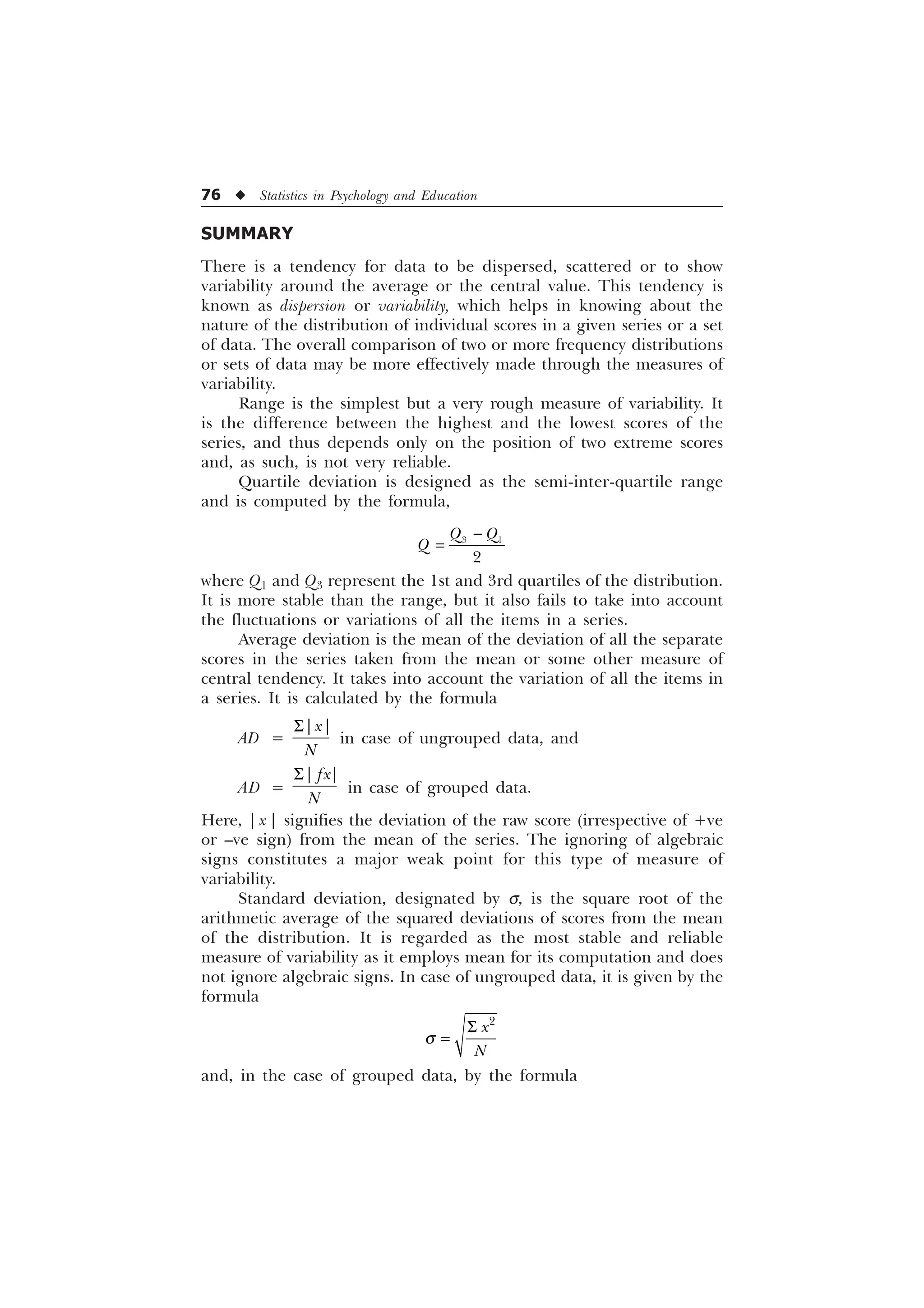

SUMMARY

The statistics, mean, median and mode, are known to be the most

common measures of central tendency. A measure of central tendency

is a sort of average or a typical value of the item in the series or some

characteristics of the members of a group. Each of these measures of

the central tendency provides a single value to represent the

characteristics of the whole group in its own way.

Mean represents the ‘average’ for an ungrouped data, the sum of

the scores divided by the total number of scores gives the value of the

mean. The mean, in the case of a grouped data is best computed with

the help of a short-cut method using the following formula:

I [

0 $ L

1

6 „

–

where A is the assumed mean,

; $

[

L

„ ,

X is the mid-point of the class interval, i the class interval, and N the

total frequencies of the distribution. Median is the score or value of

that central item which divides the series into two equal parts. Hence

when N is odd (N + 1)/2-th measure, and when N is even, the average

of (N/2)-th and [(N/2) + 1]-th item’s measure provides the value of the

median. In the case of grouped data, it is computed by the formula

–

G

1 )

0 / L

I

where L represents the lower limit of the median class, F, the total of

all frequencies before the median class, and f, the frequency of the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/stats-s-241206101830-e3d4cc67/75/Stats-S-K-Mangal-statistics-textook-in-pdf-63-2048.jpg)

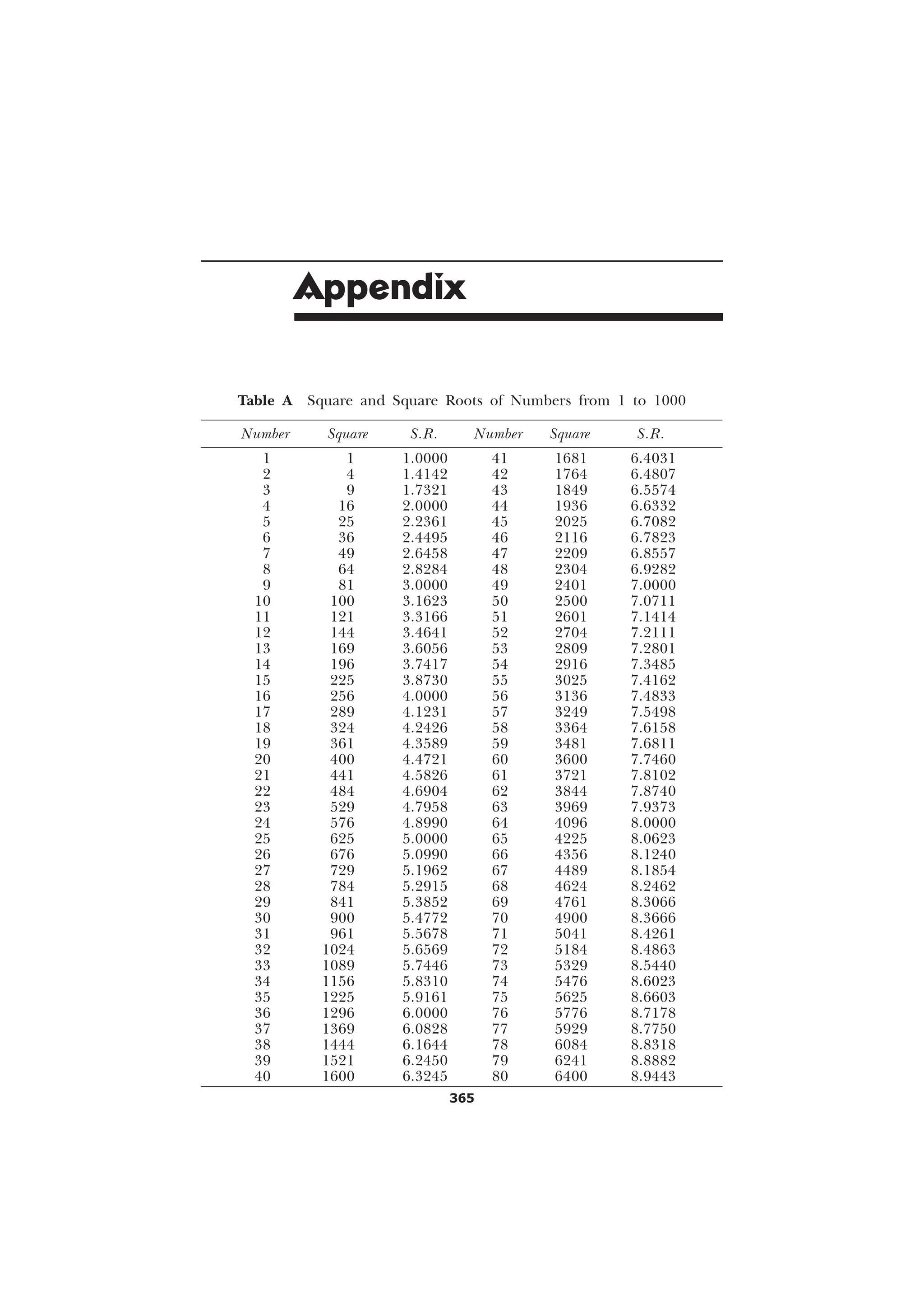

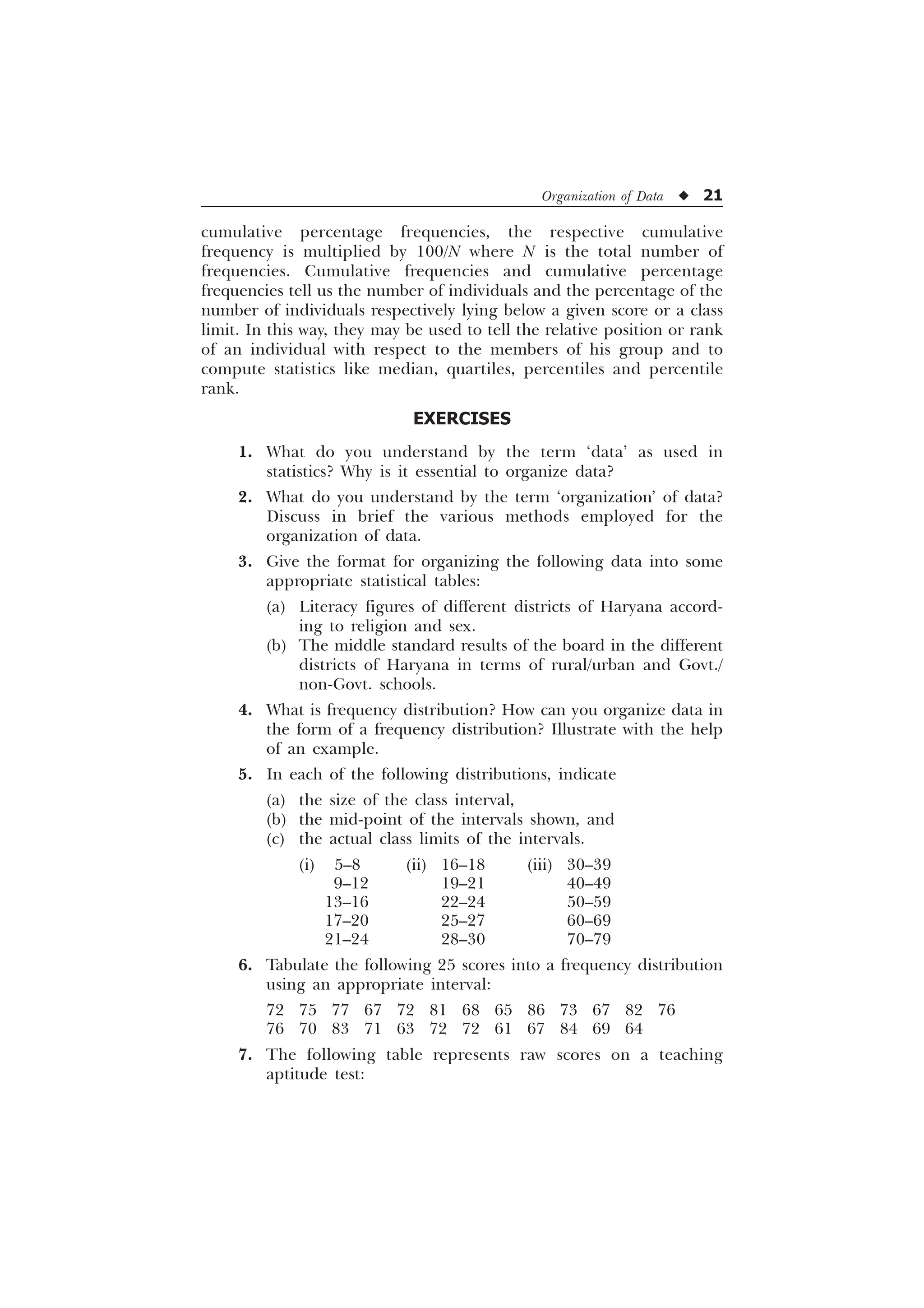

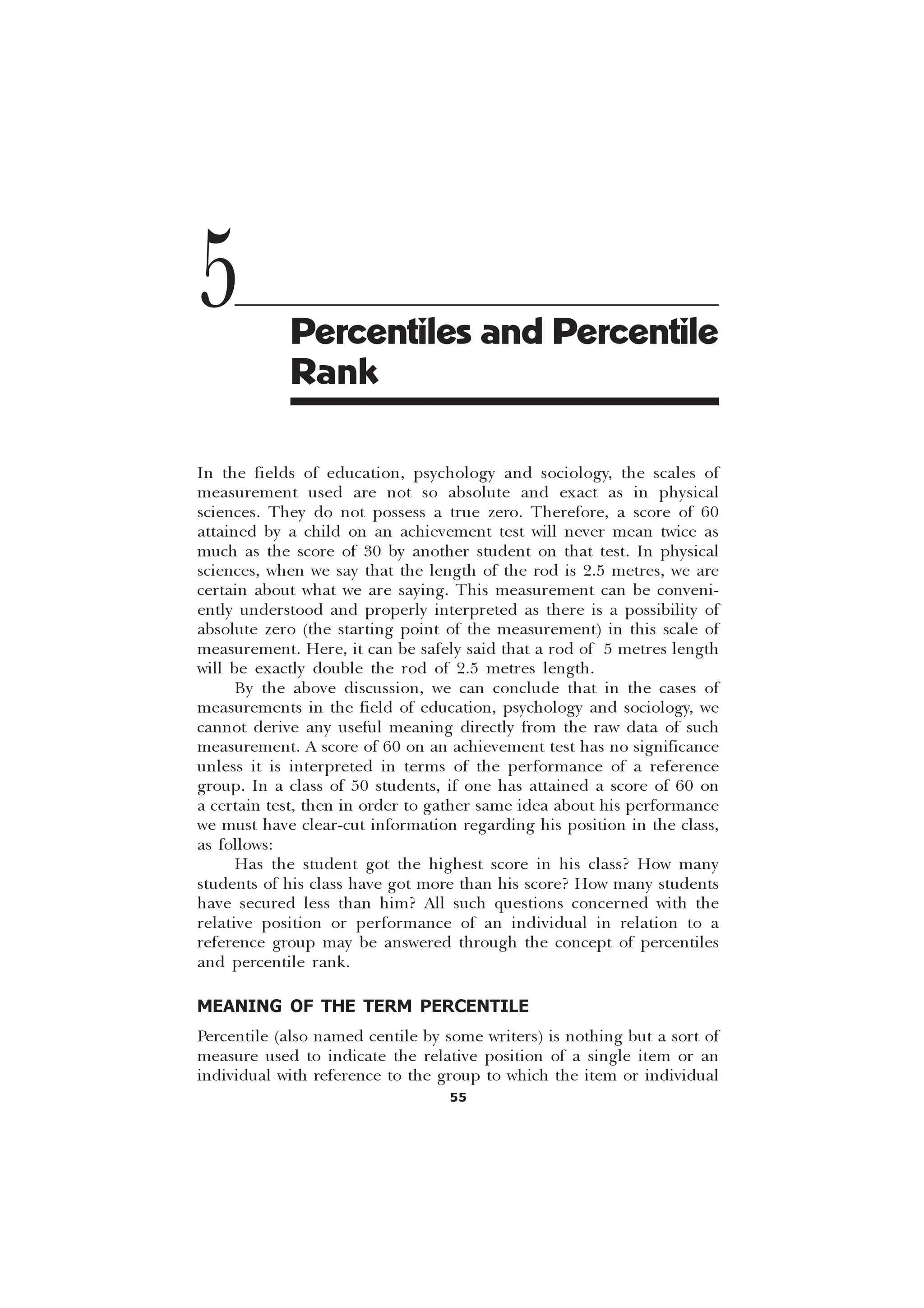

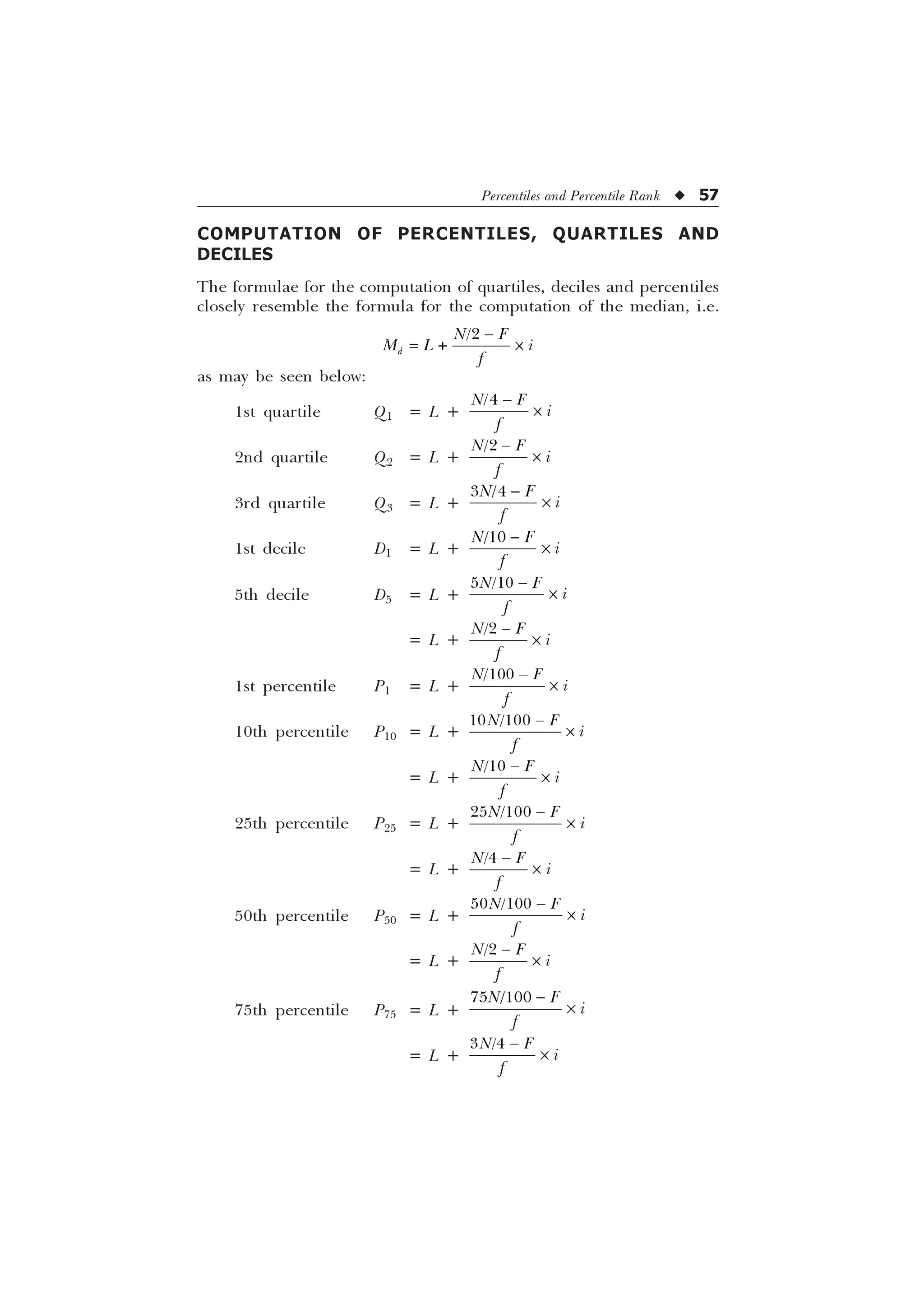

![62 u Statistics in Psychology and Education

Here, rank R of the desired score 17 is 14 and N is given as 20.

Putting these figures into the formula, we get

PR= 100 –

–

= 100 –

= 100 – 67.5 =32.5 or 32

[Ans. The percentile rank of the score 17 is 32.]

Example 5.3: In an entrance examination, a candidate ranks 35 out

of 150 candidates; find out his percentile rank.

Solution. The percentile rank is given by the formula

PR = 100 –

5

1

In this case,

R = 35 and N = 150

Hence

PR = 100 –

–

= 100 –

= 100 – 23 = 77

[Ans. Percentile rank is 77.]

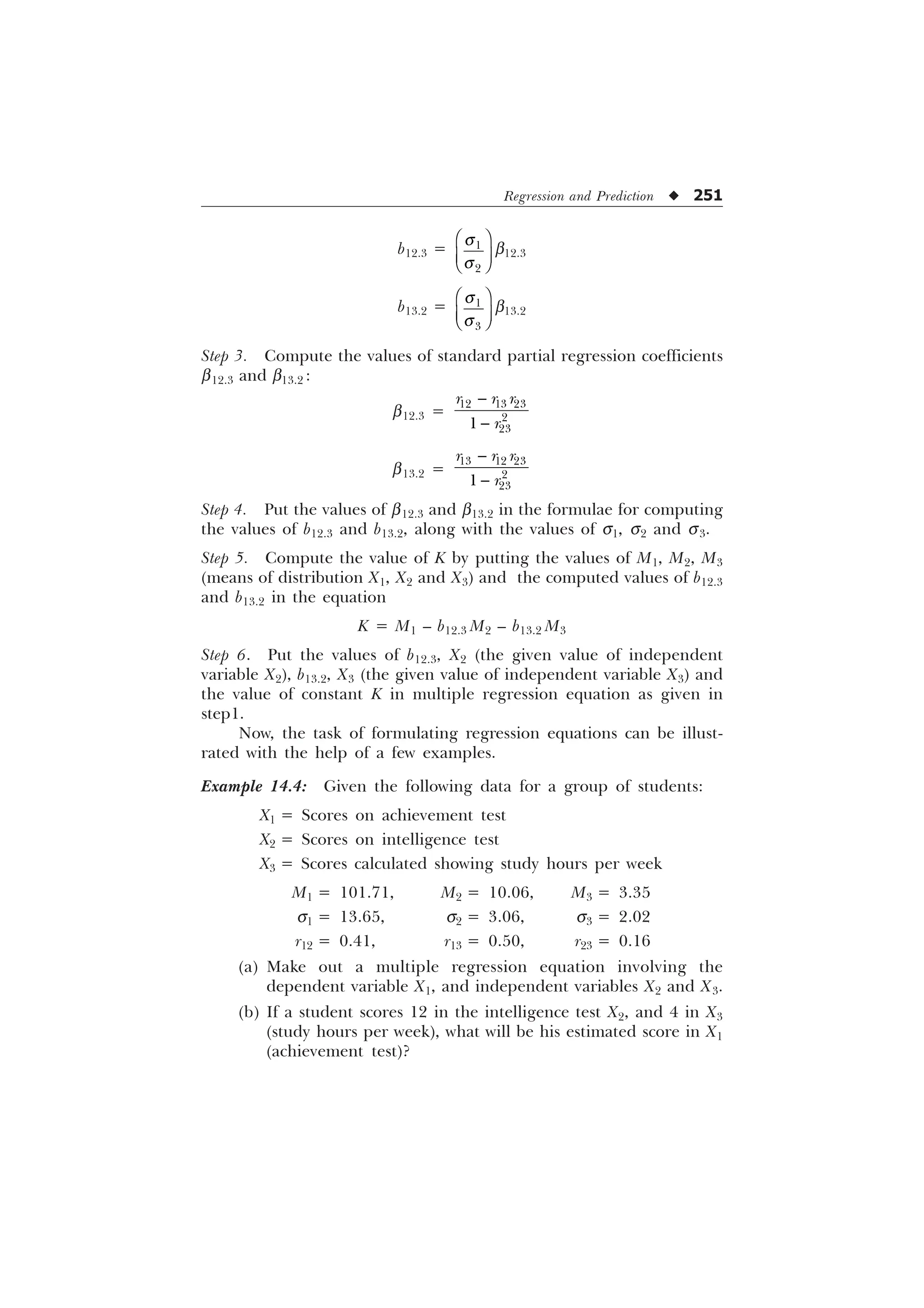

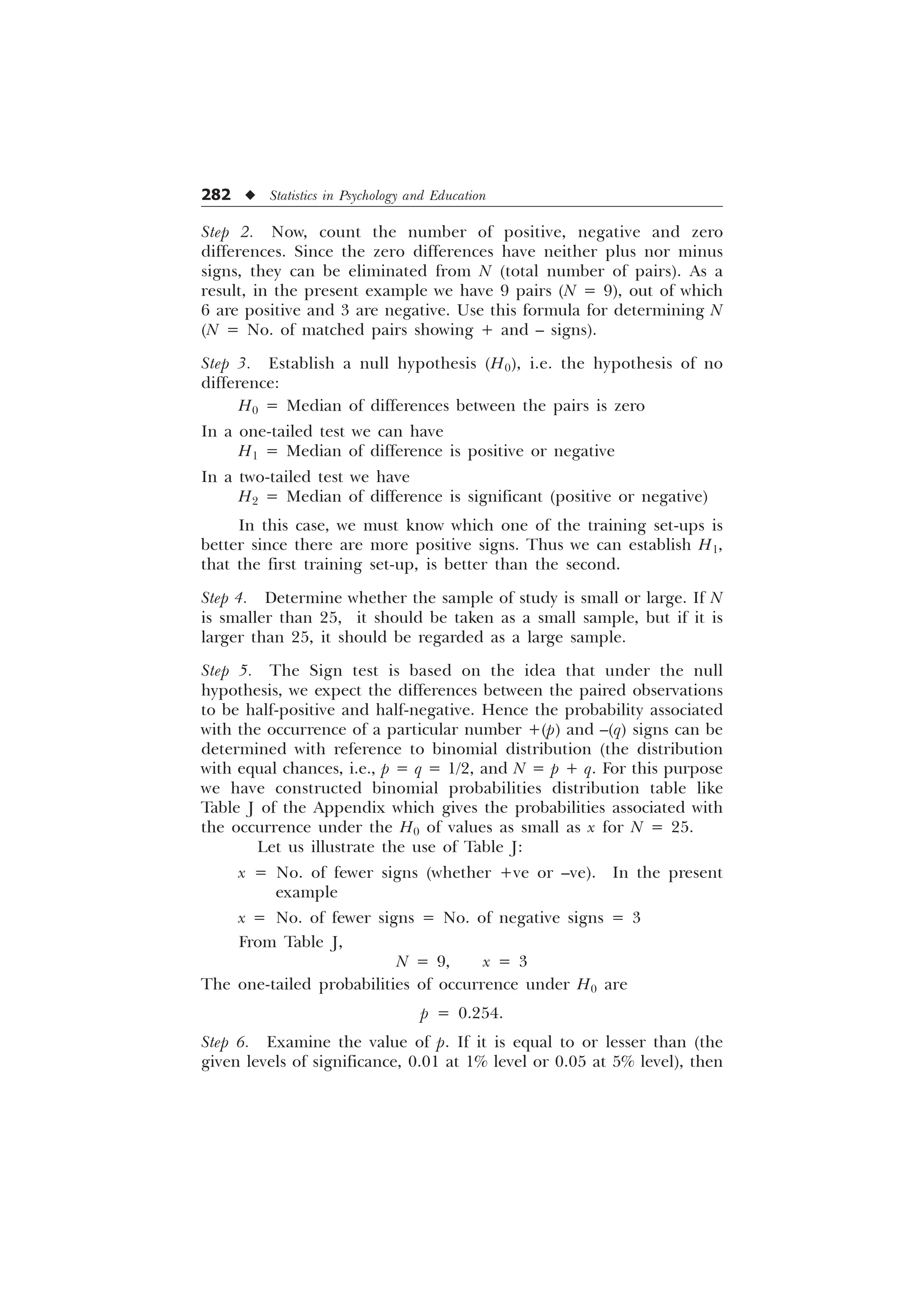

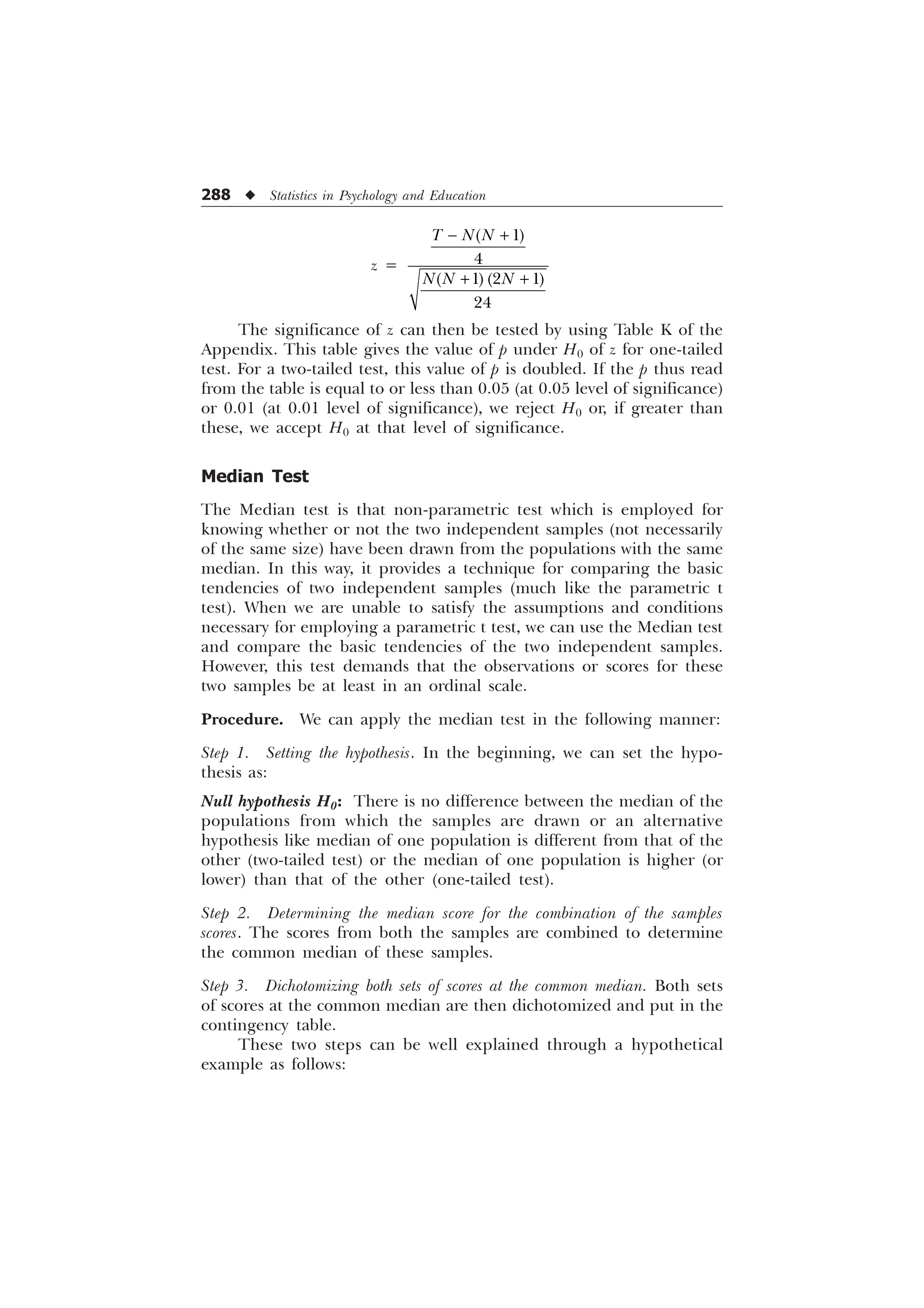

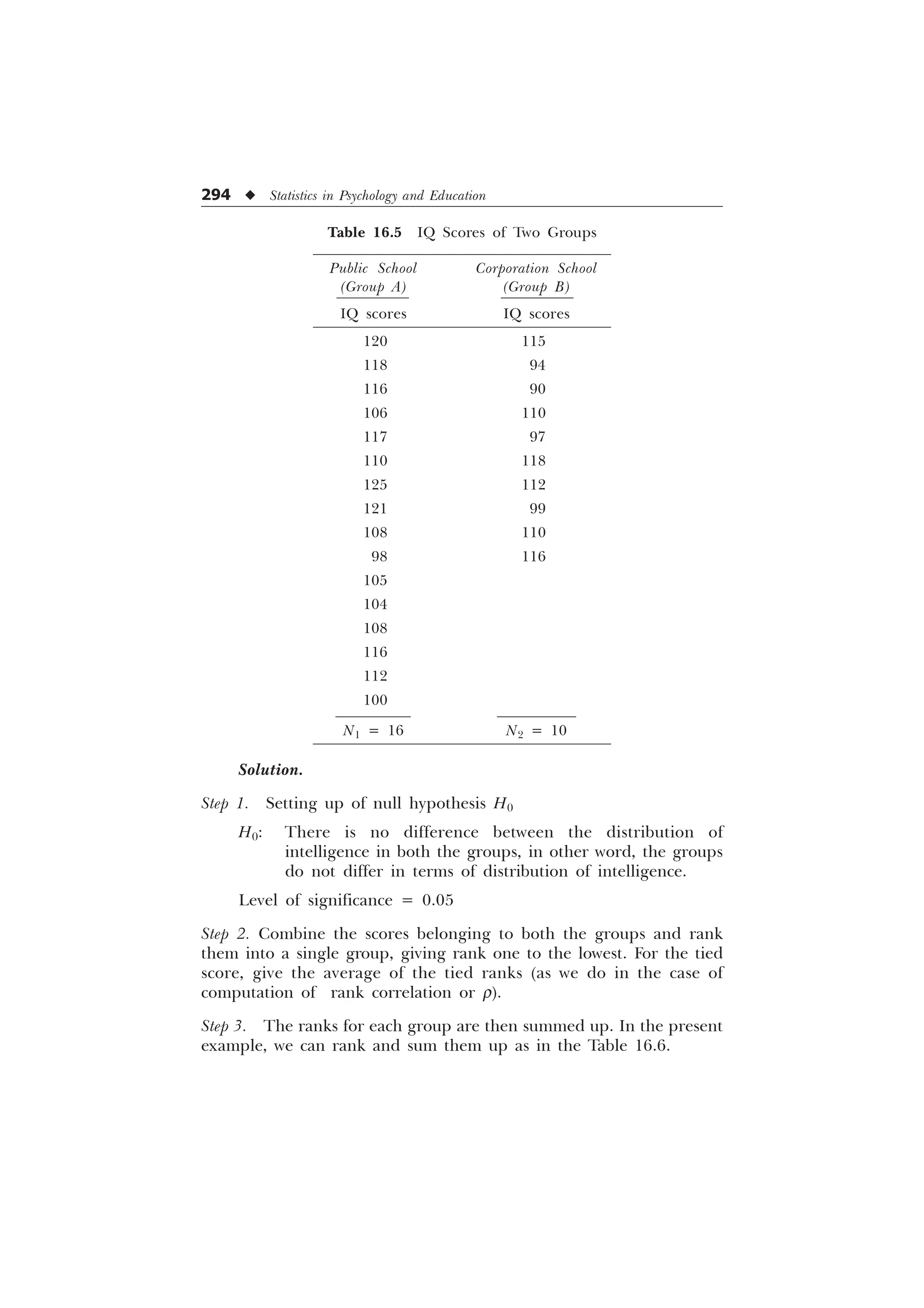

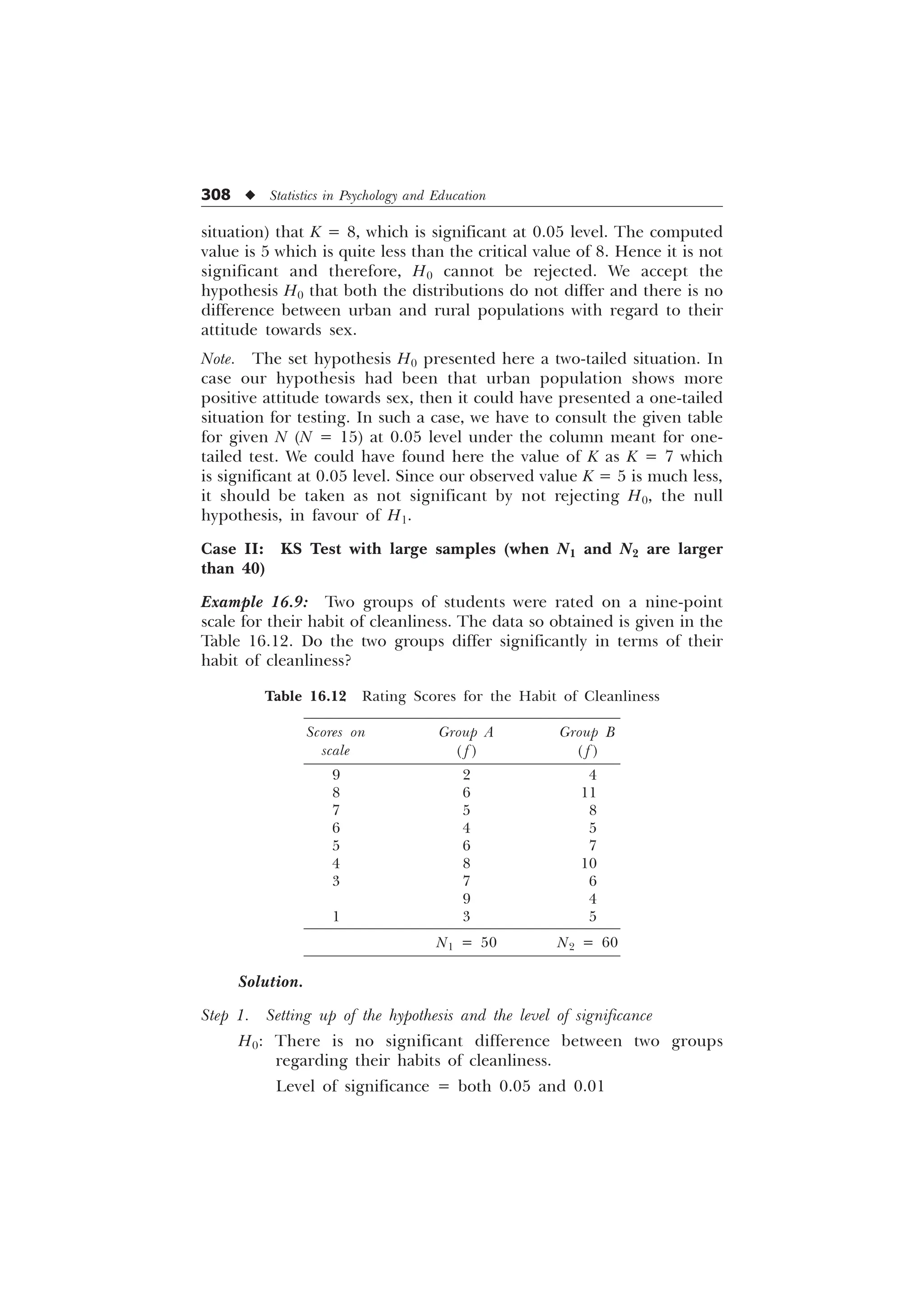

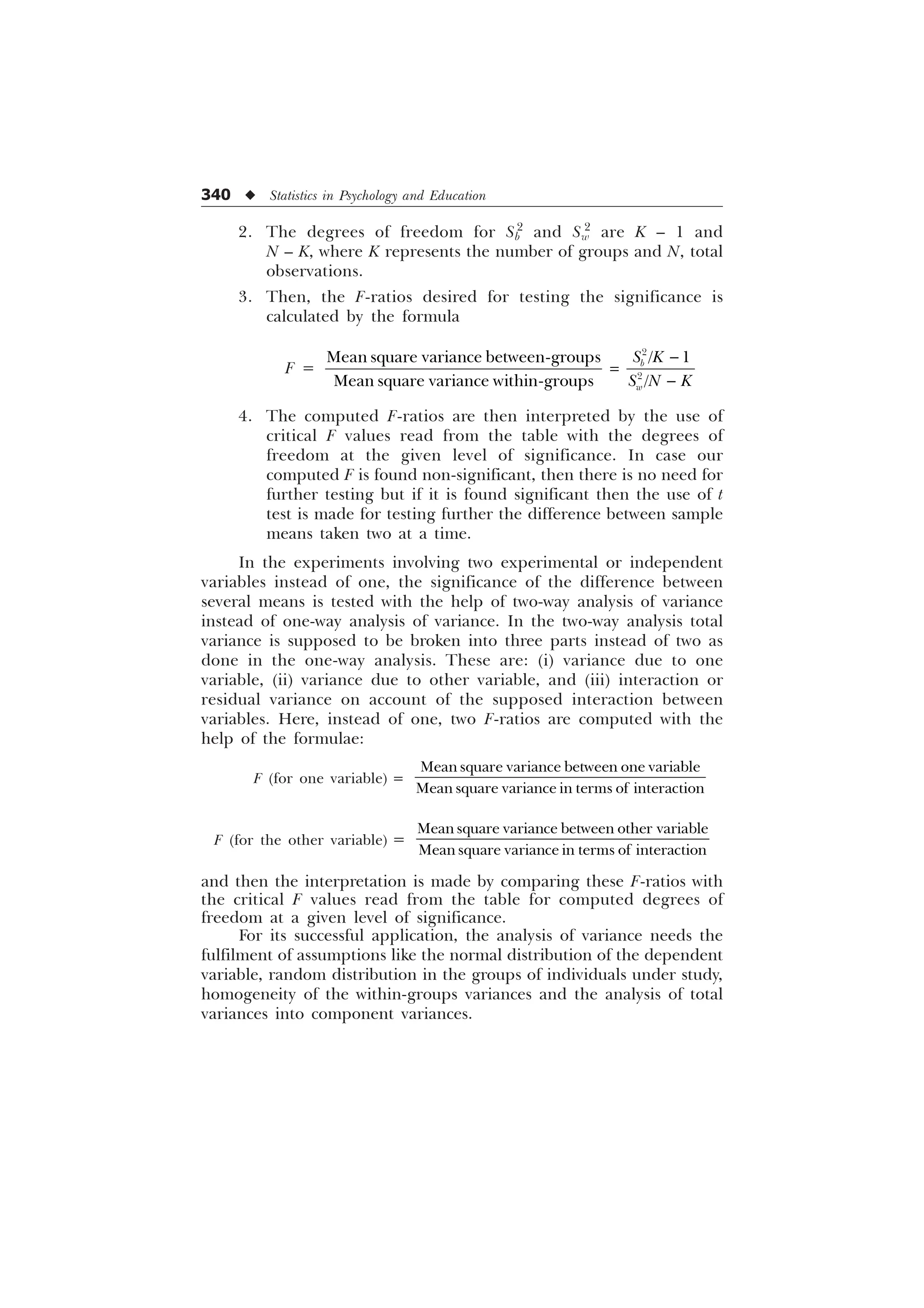

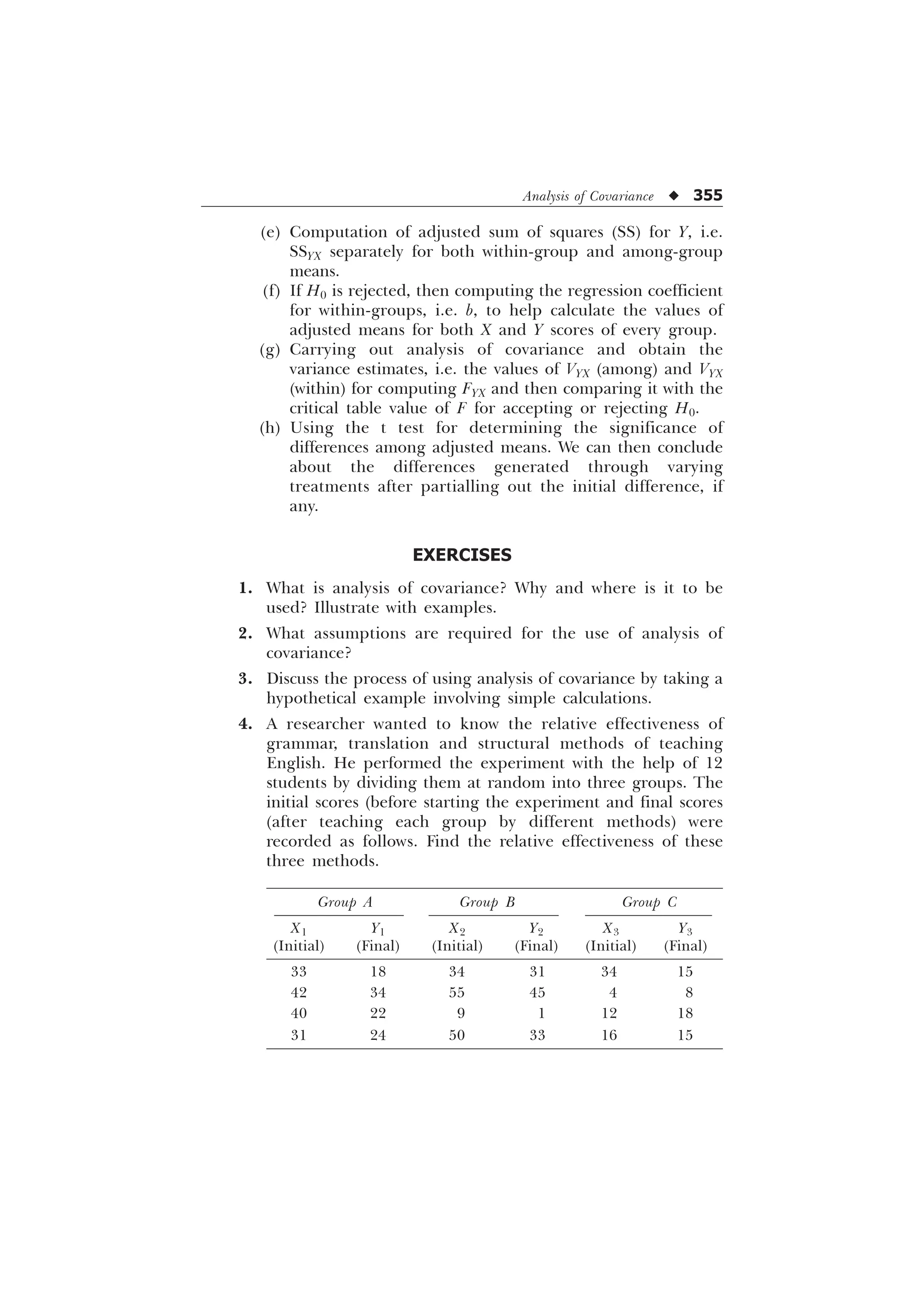

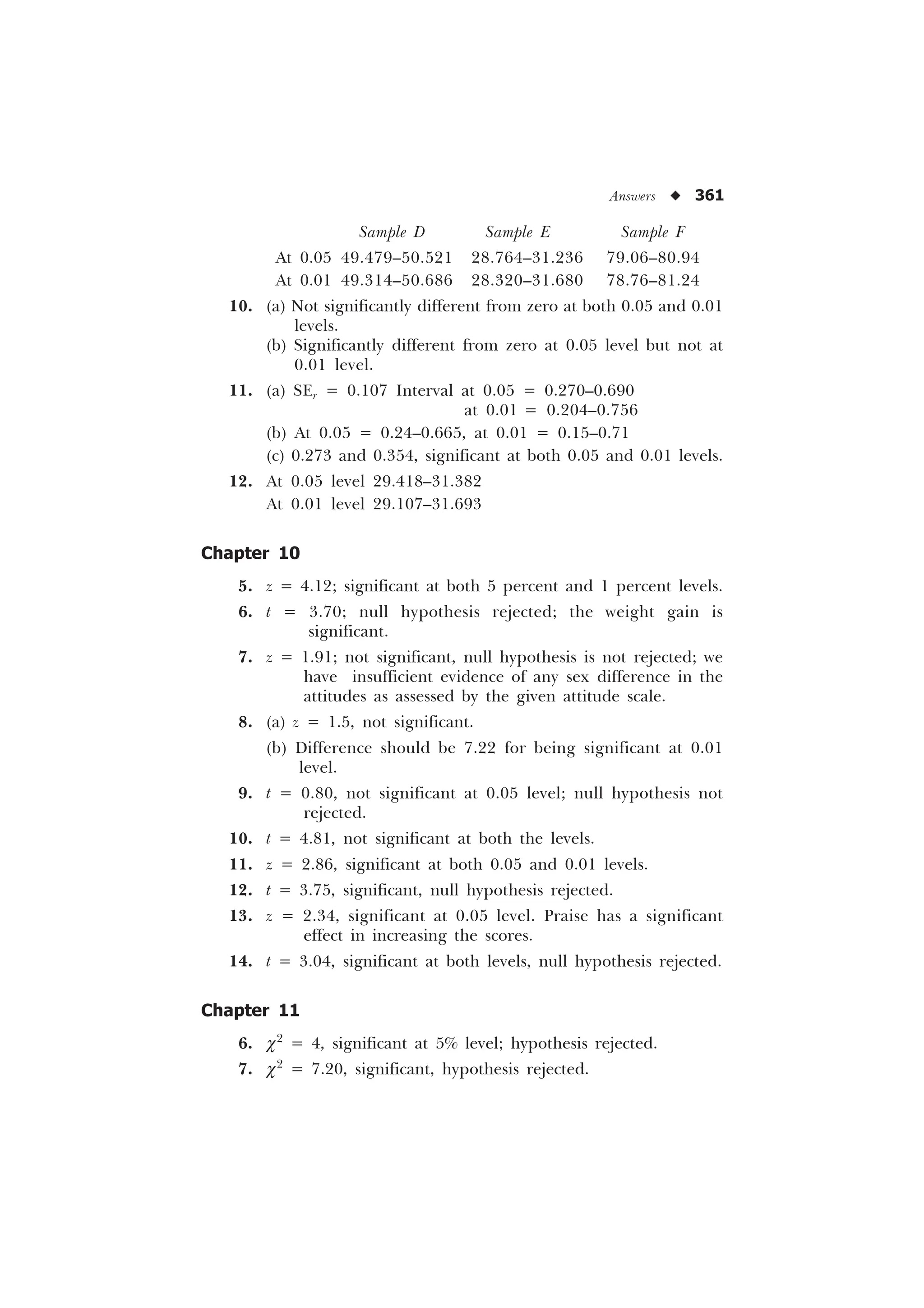

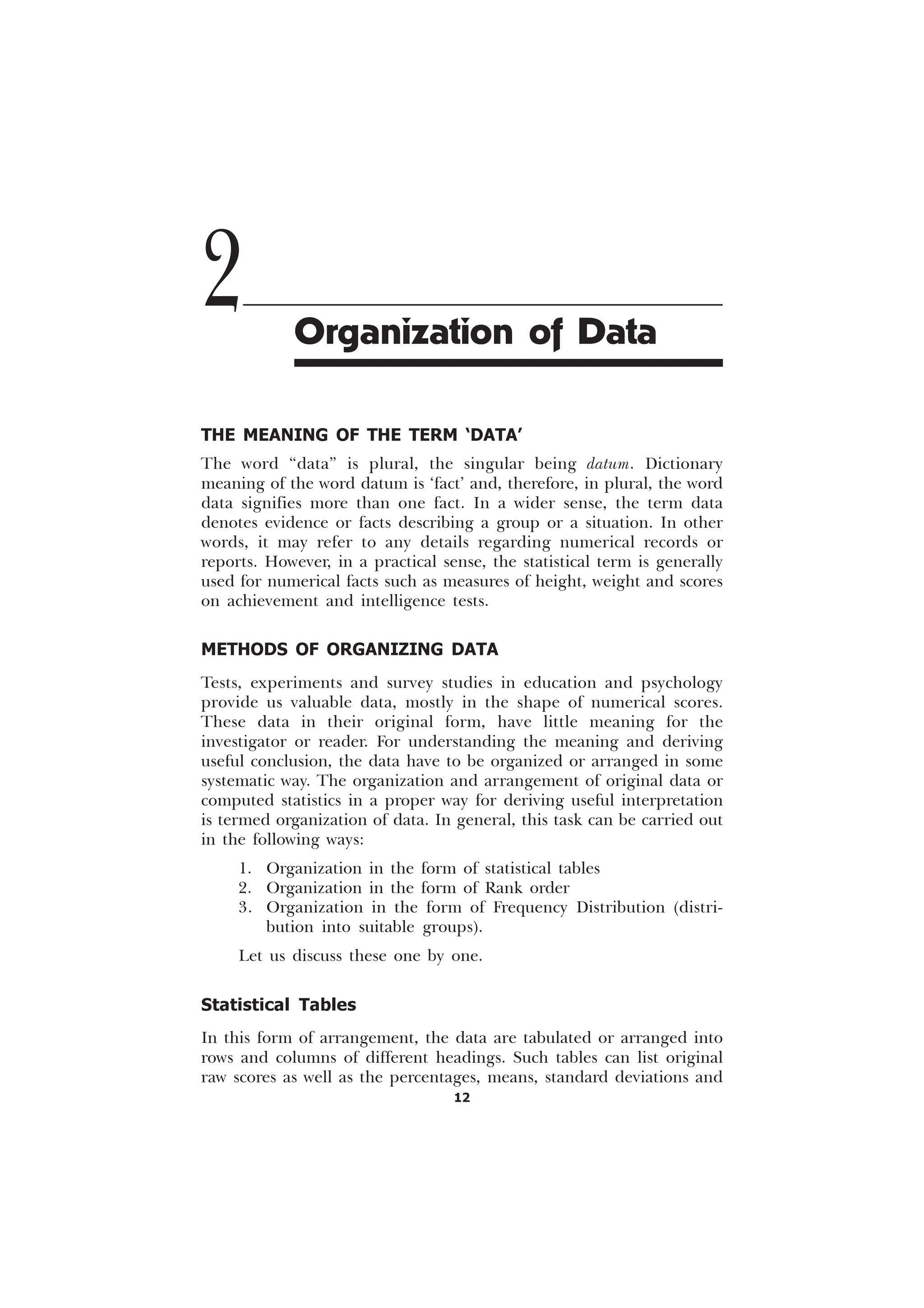

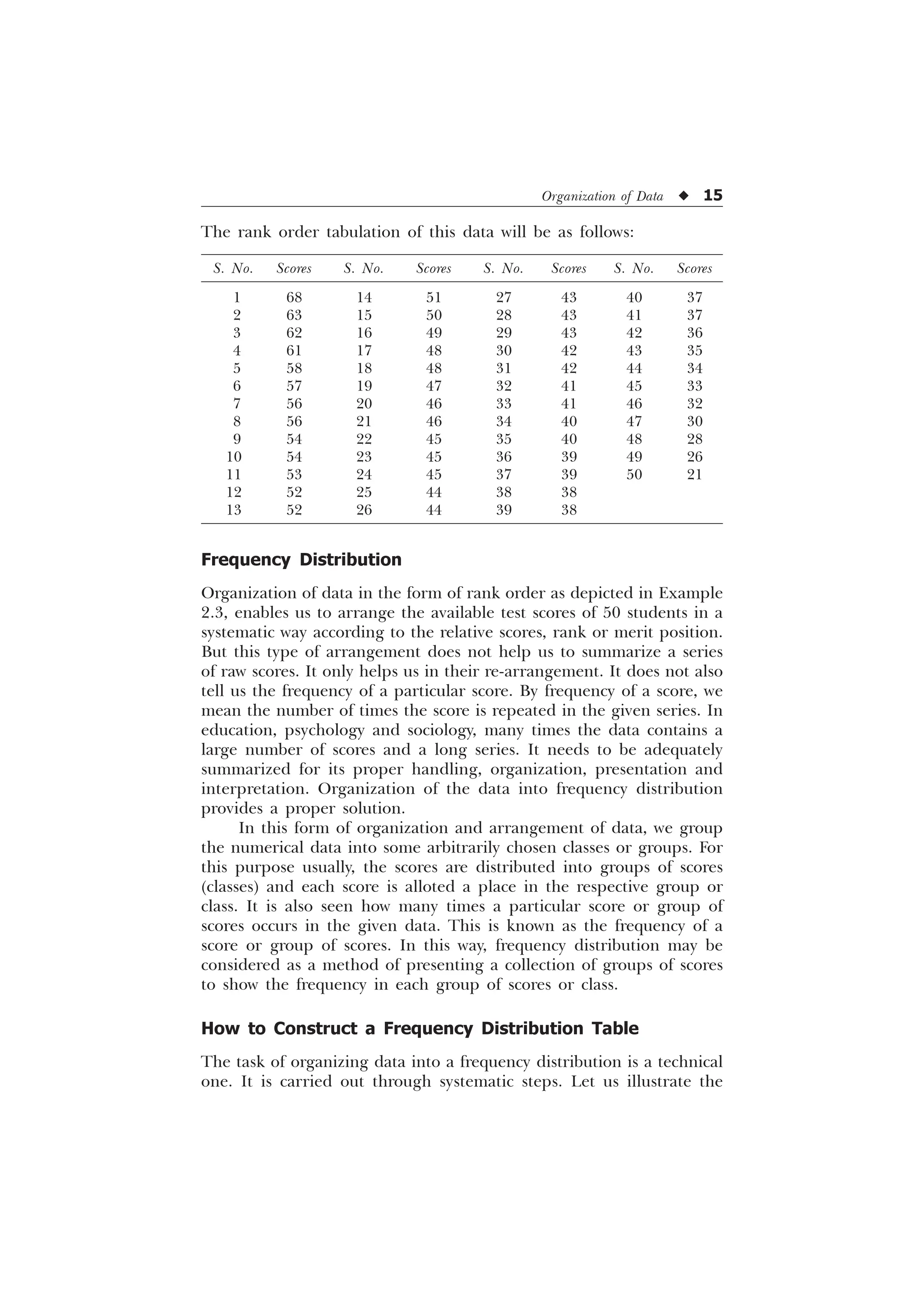

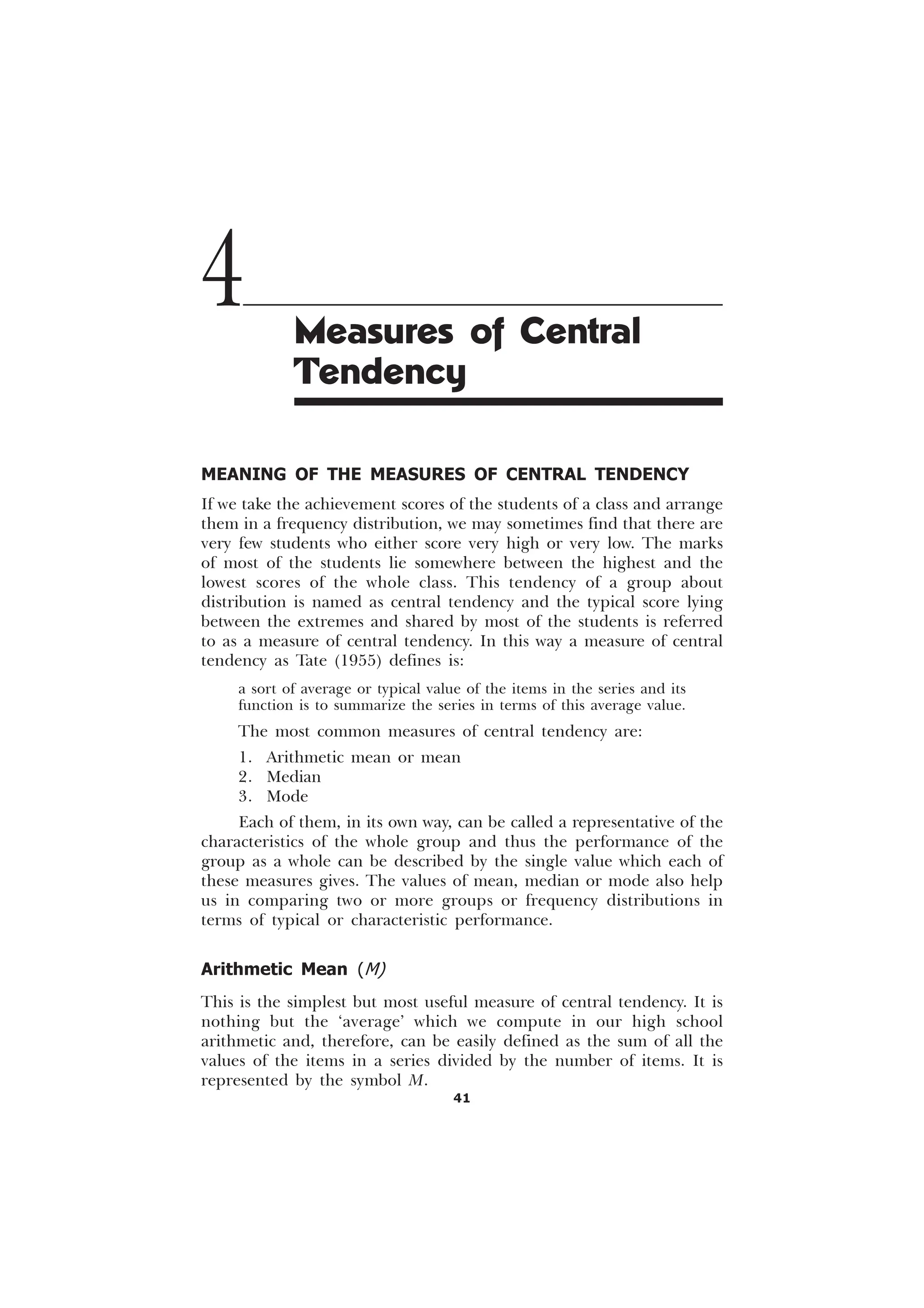

From grouped data or frequency distribution

1st Method. (Direct method not needing any formula). For illus-

trating the working of this method, let us take the following

distribution (same as taken for the computation of quartiles, deciles

and percentiles) and calculate the percentile rank of the score 22.

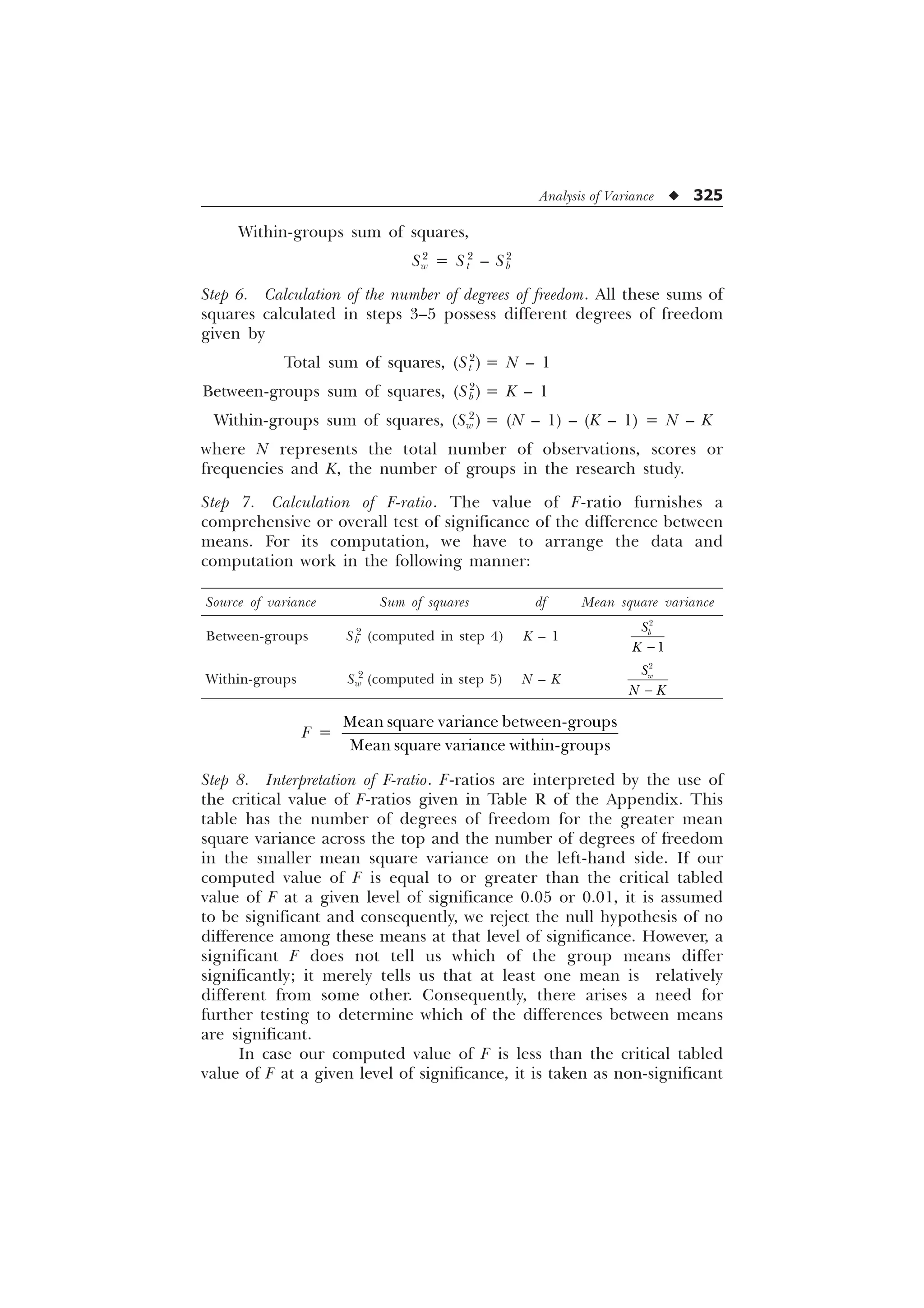

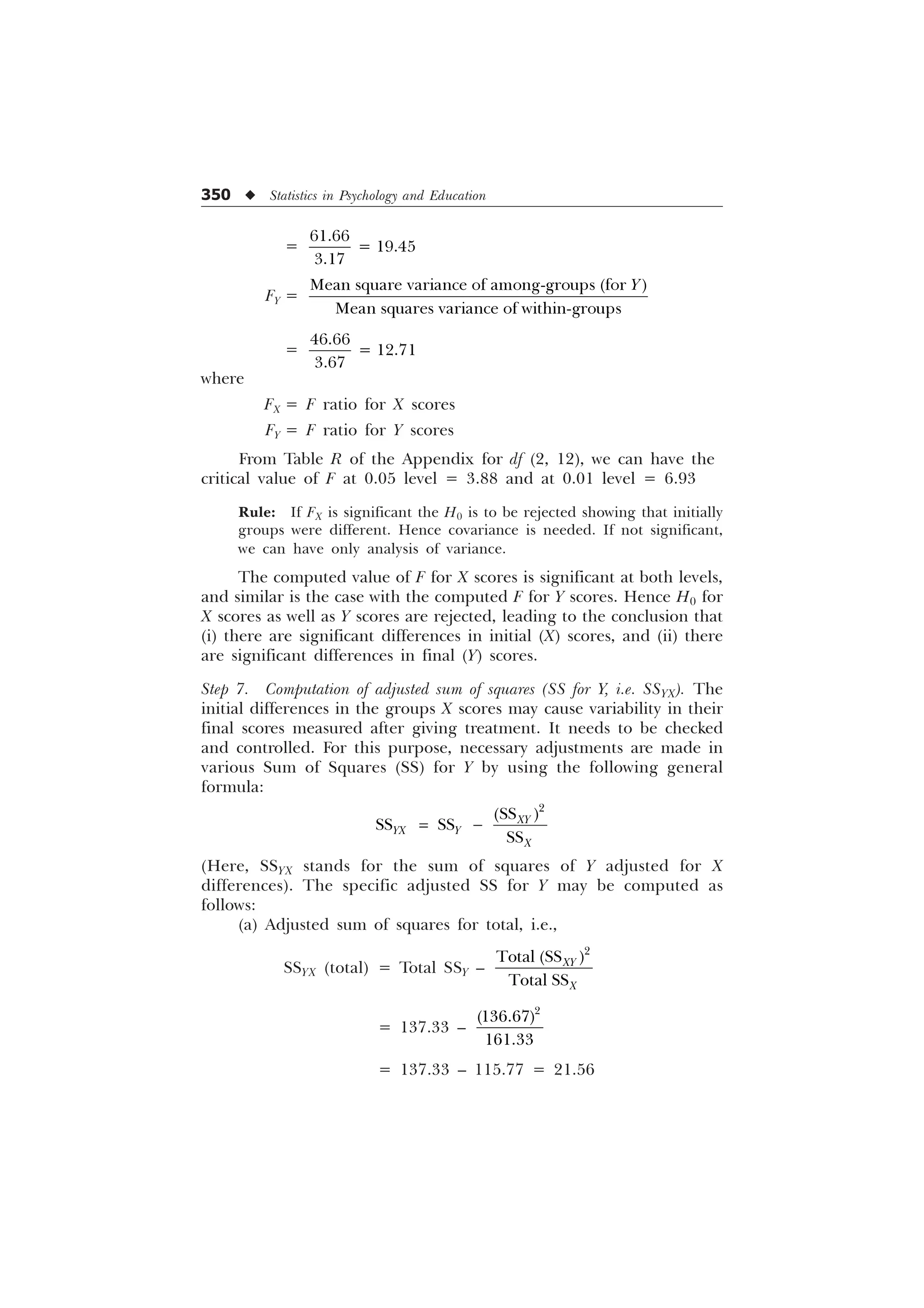

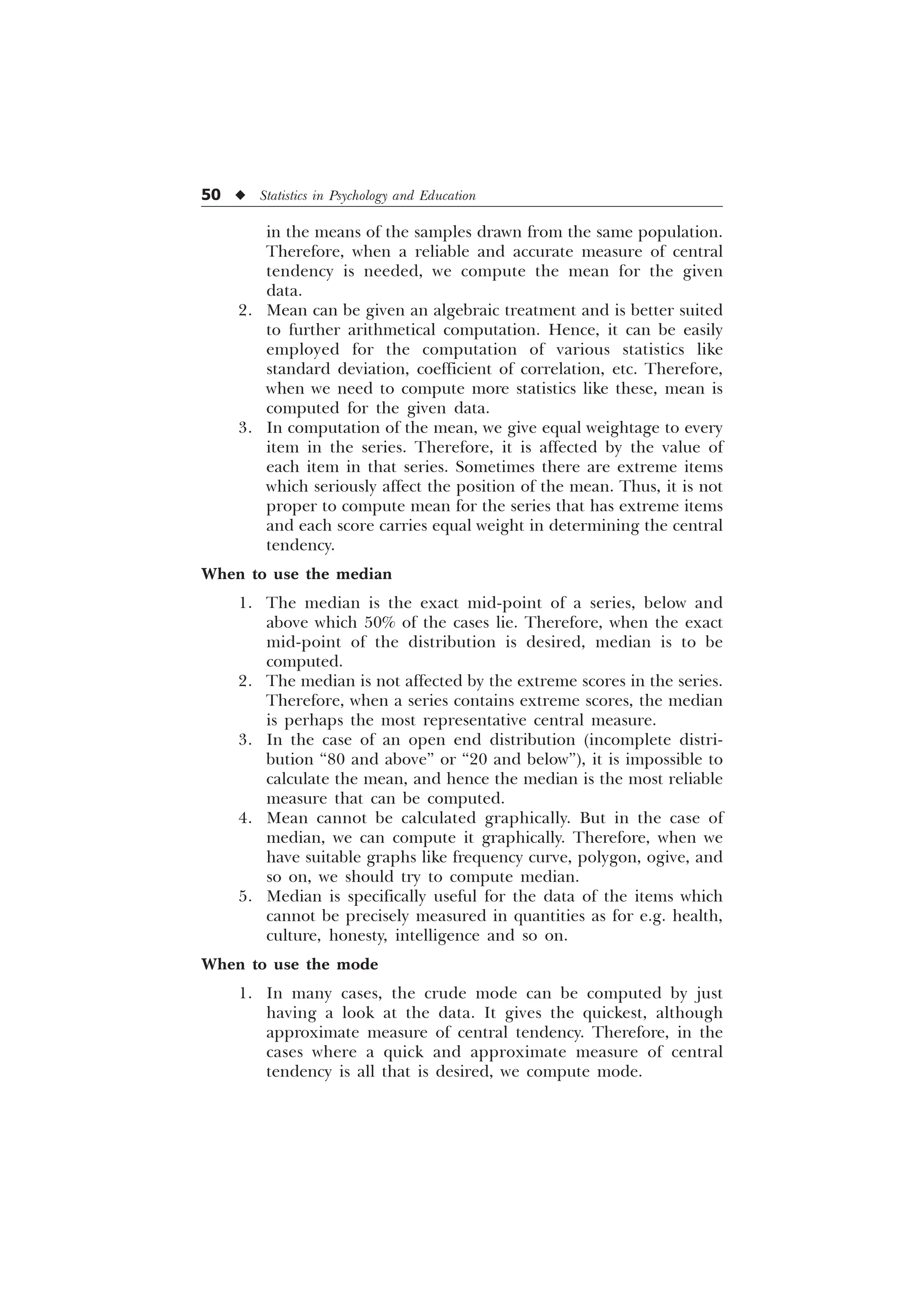

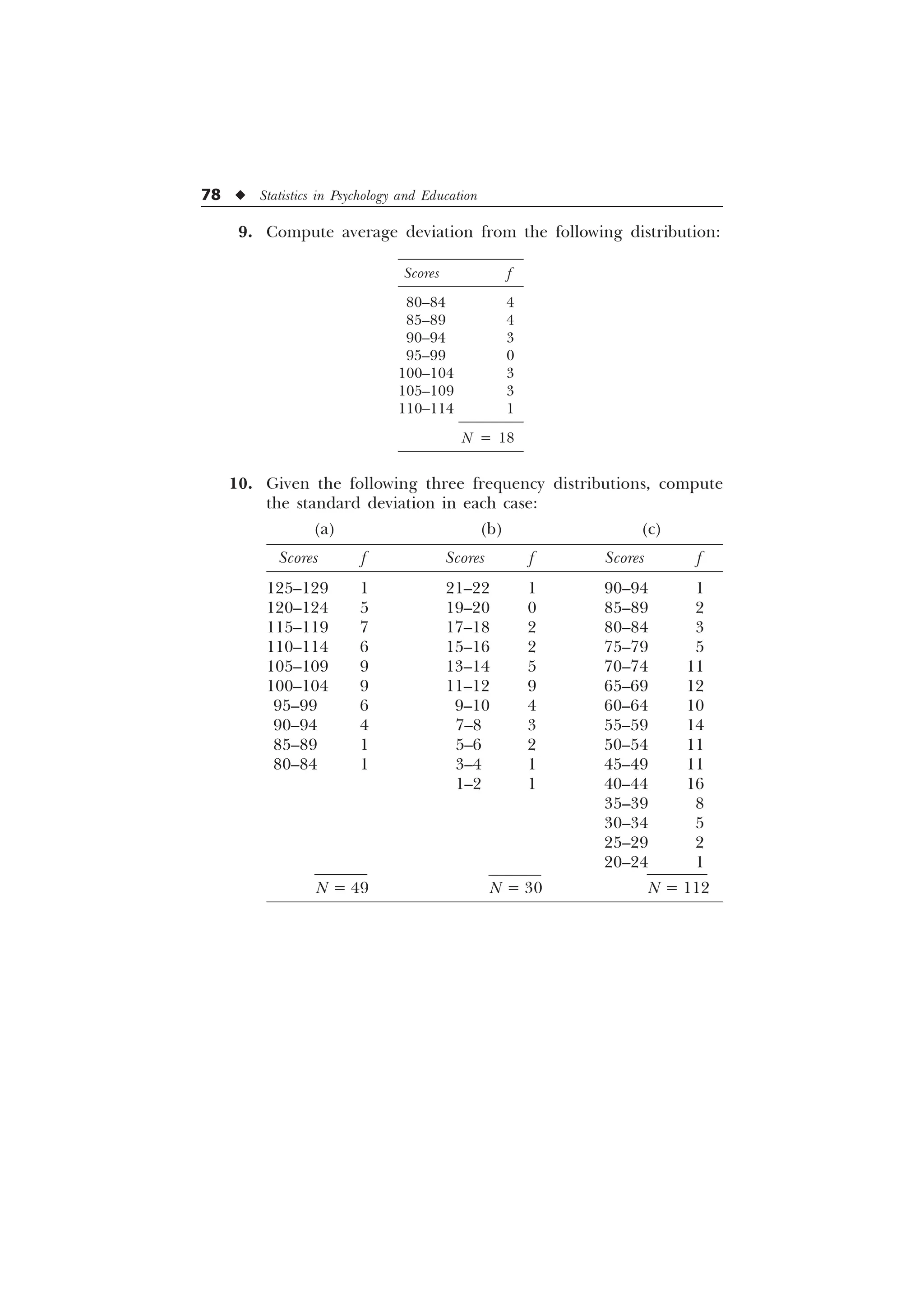

Example 5.4

Scores f

70–79 3

60–69 2

50–59 2

40–49 3

30–39 5

20–29 4

10–19 3

0–9 2

N = 24](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/stats-s-241206101830-e3d4cc67/75/Stats-S-K-Mangal-statistics-textook-in-pdf-74-2048.jpg)

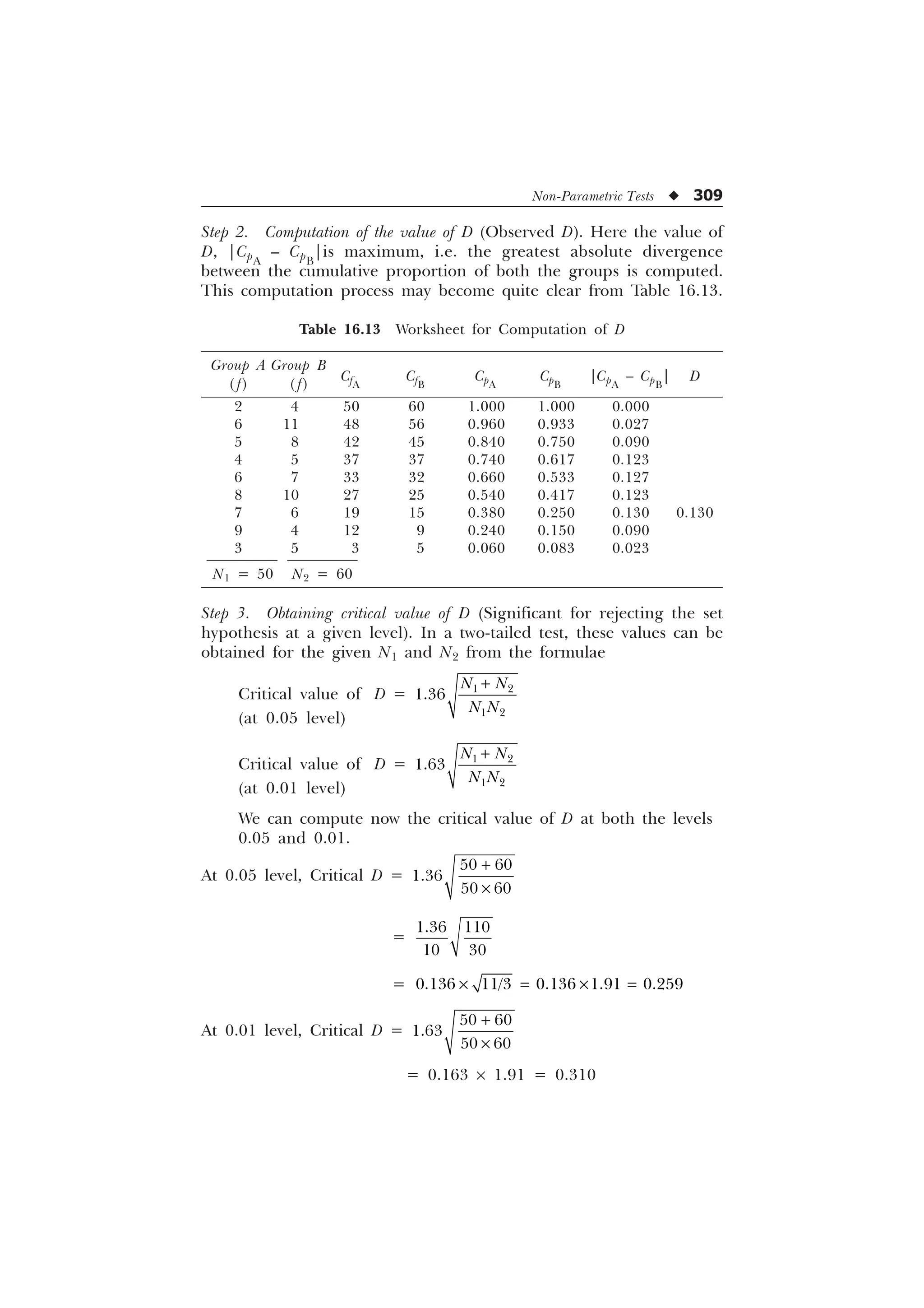

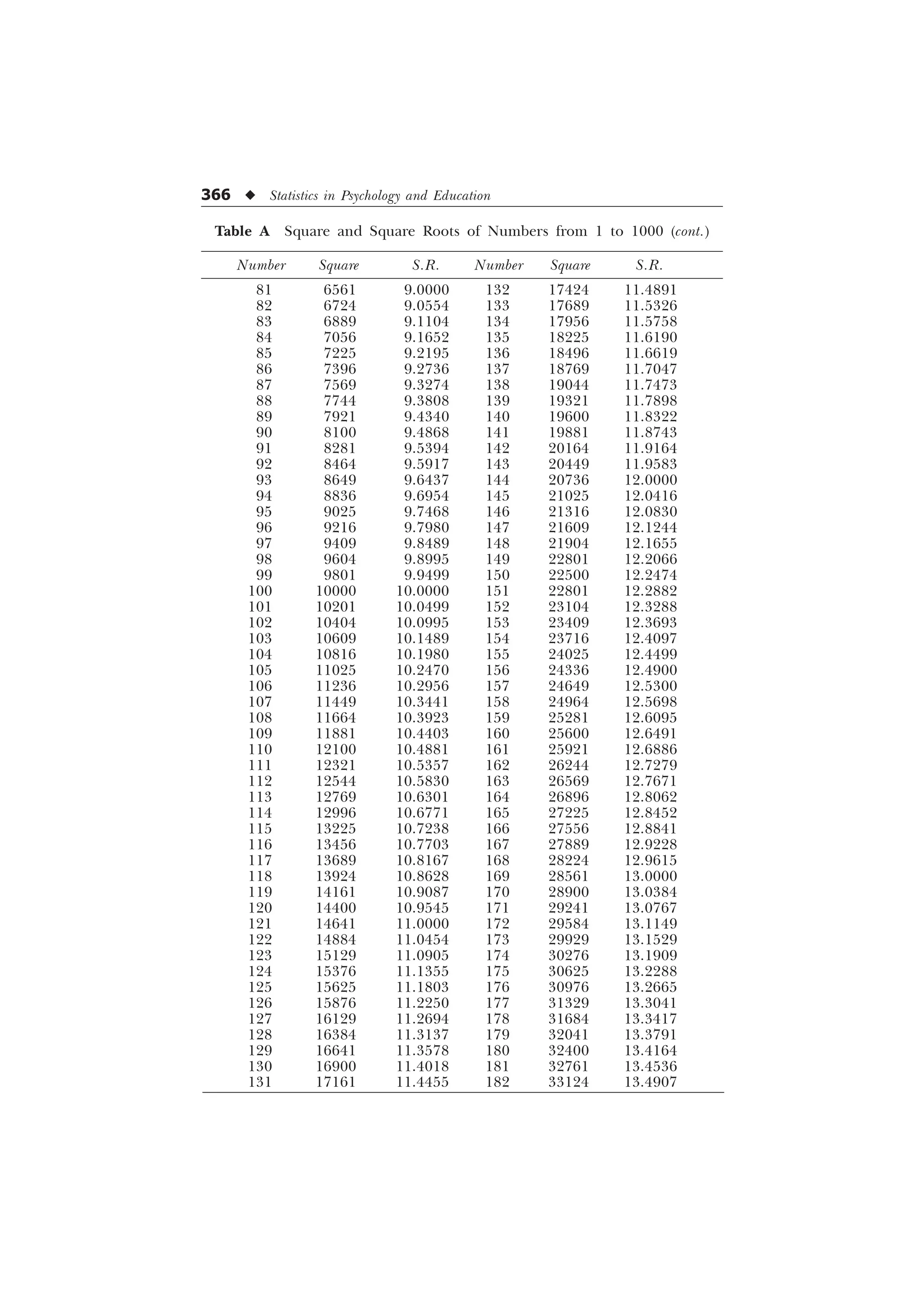

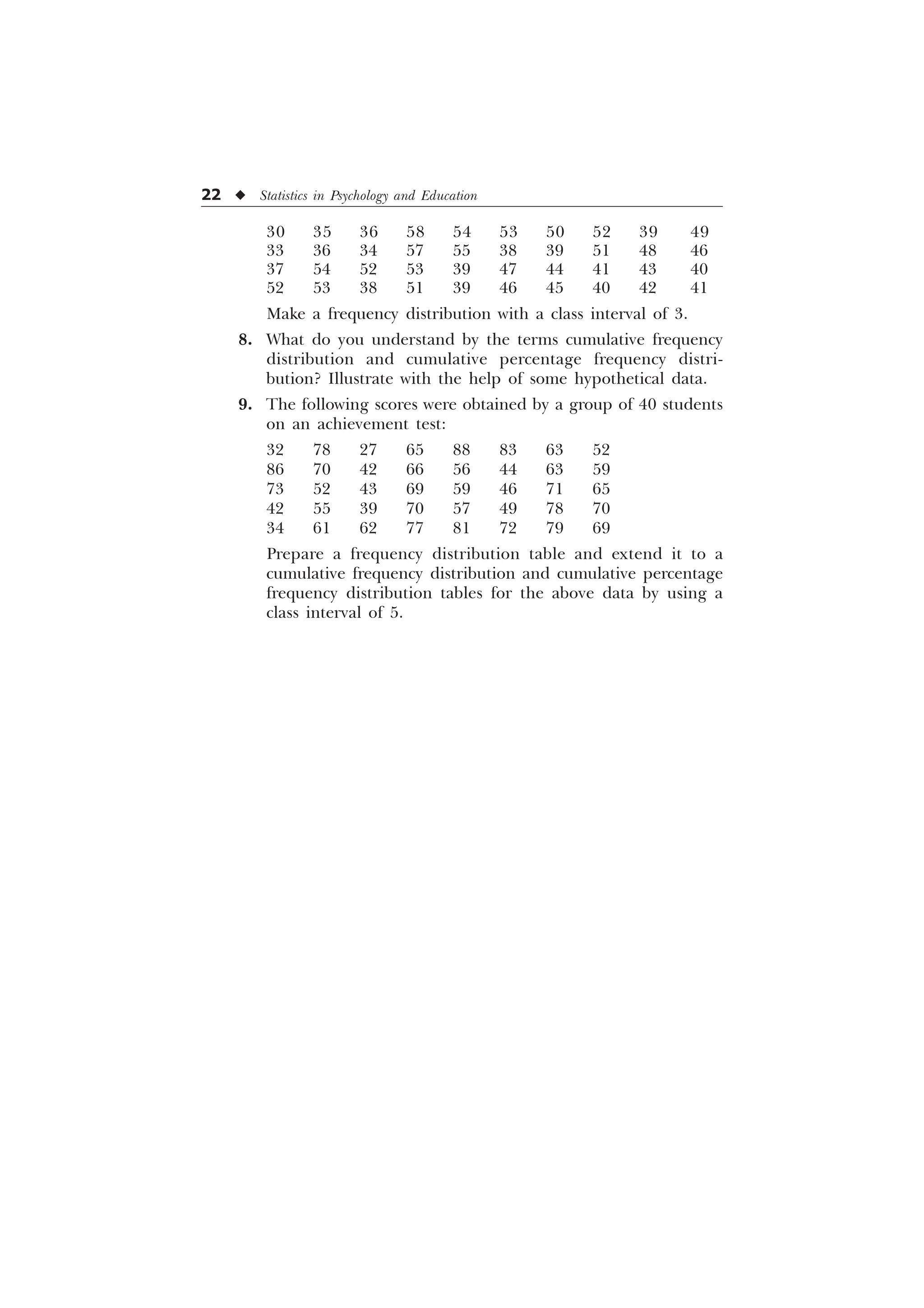

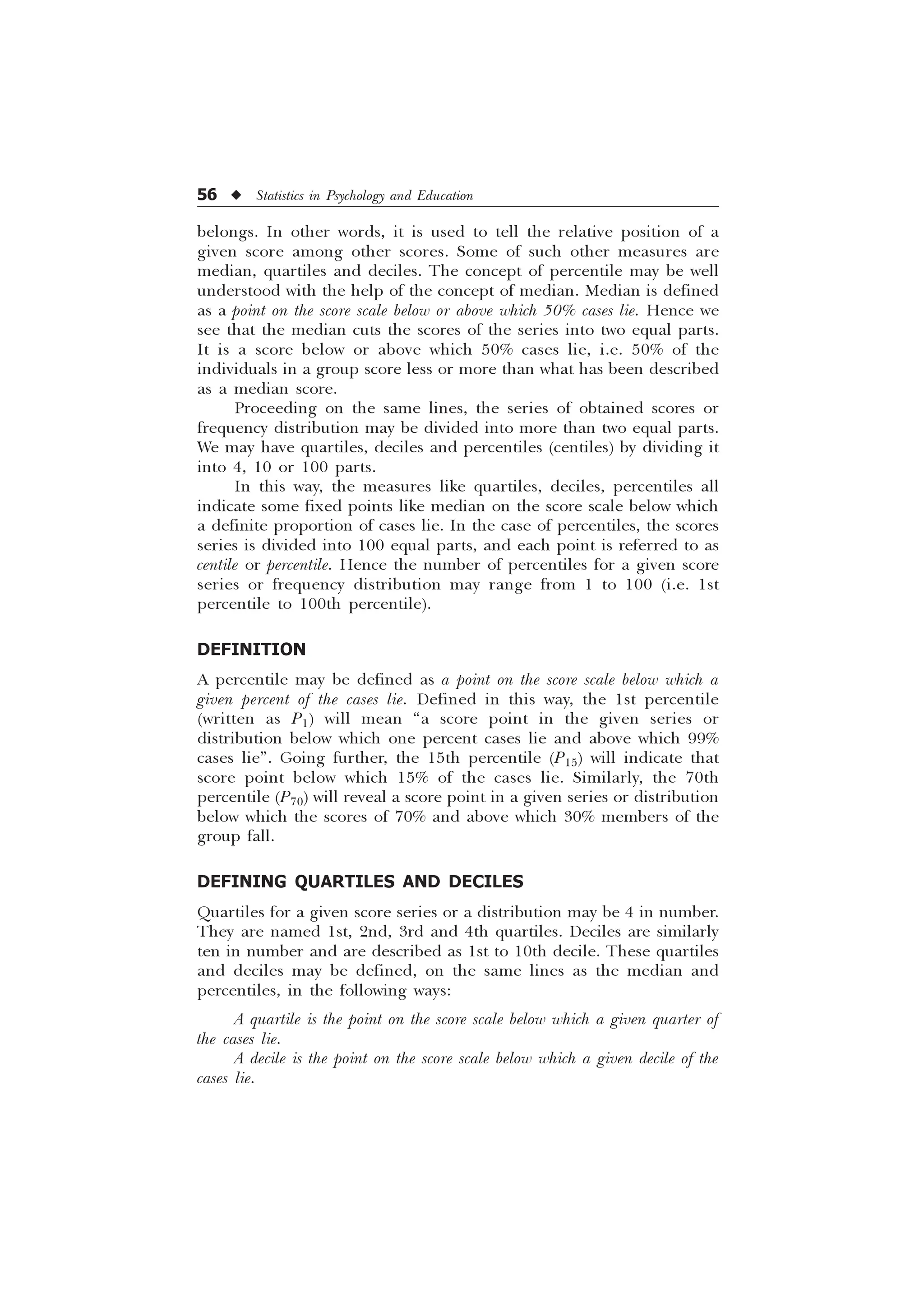

![72 u Statistics in Psychology and Education

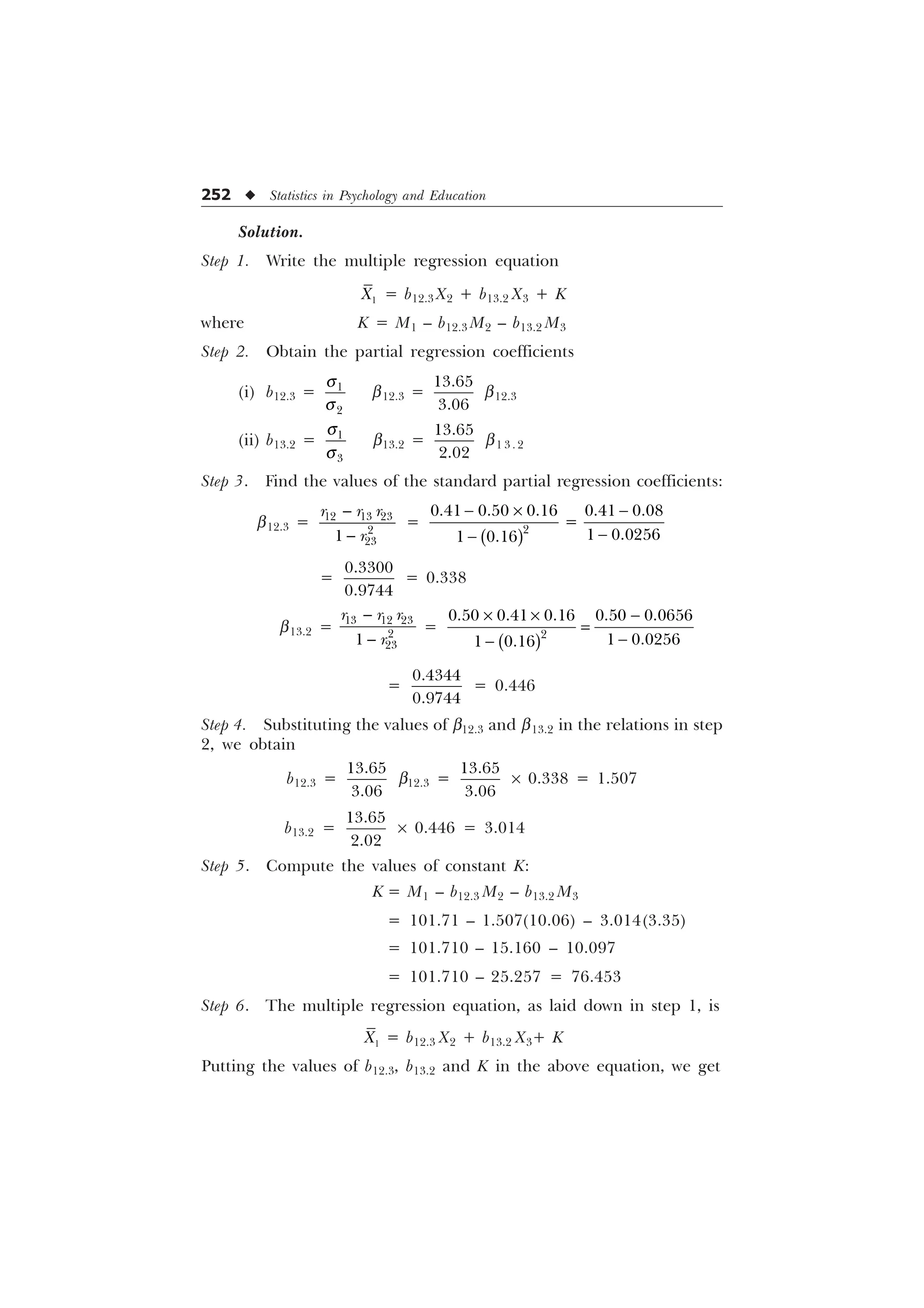

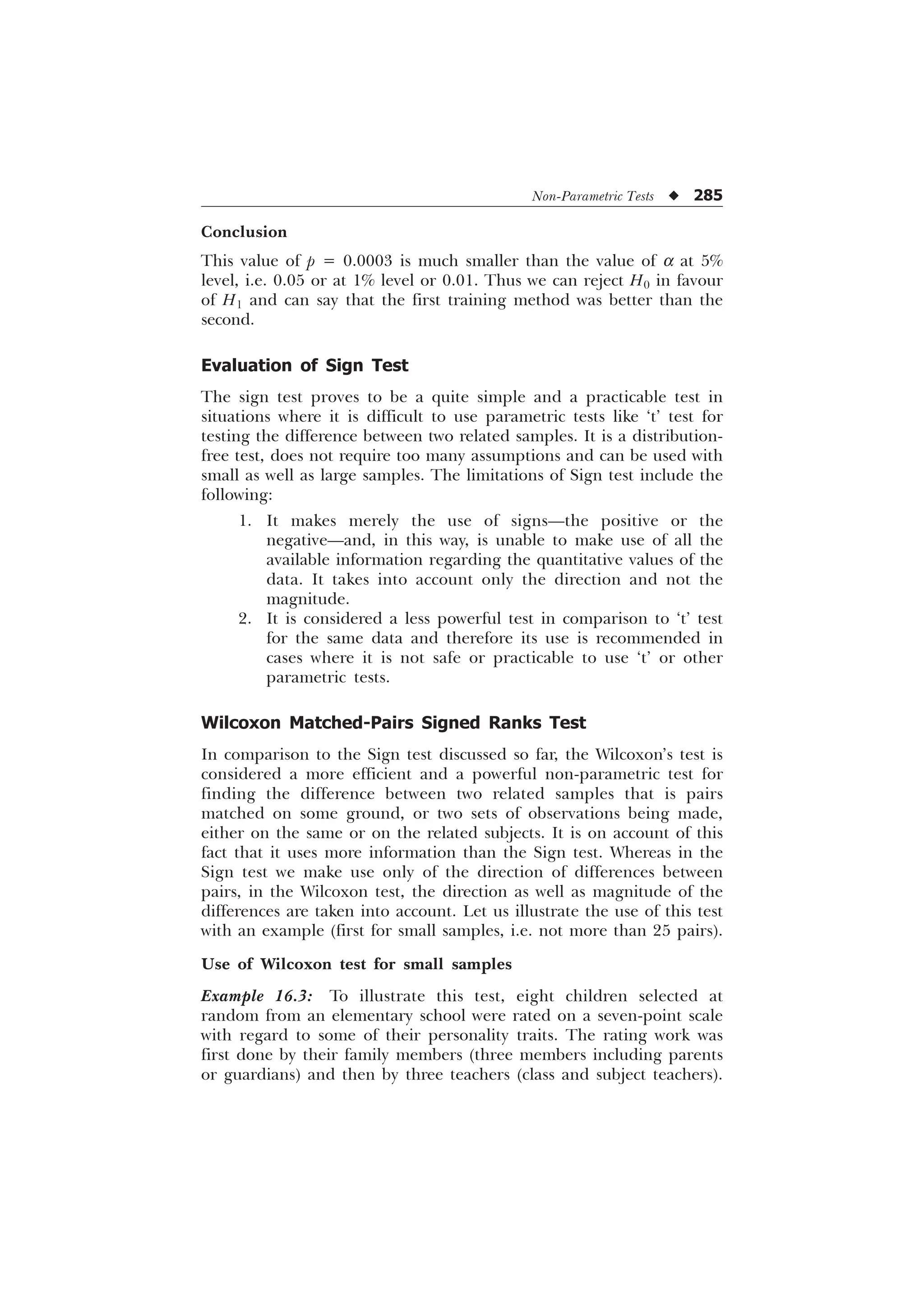

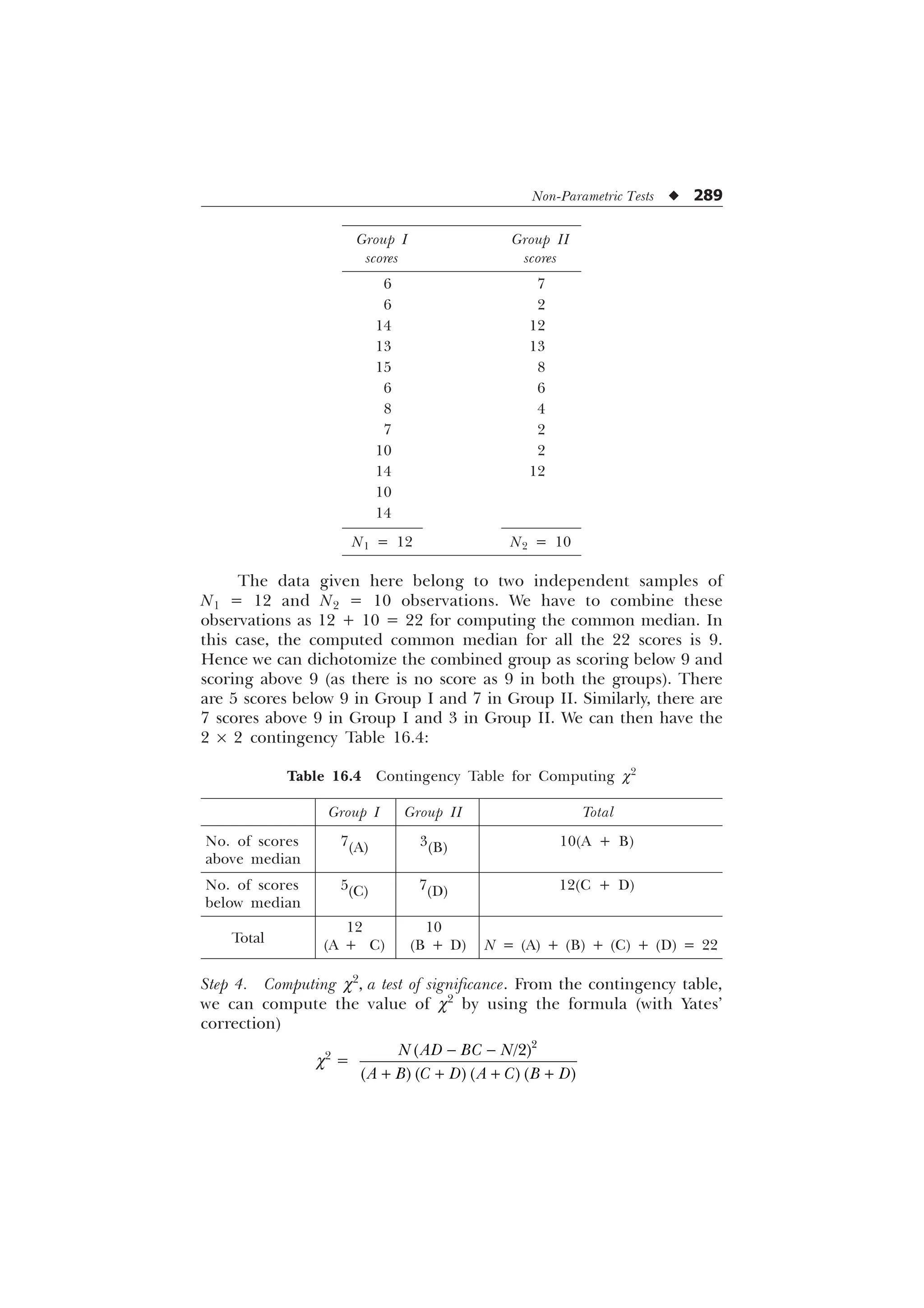

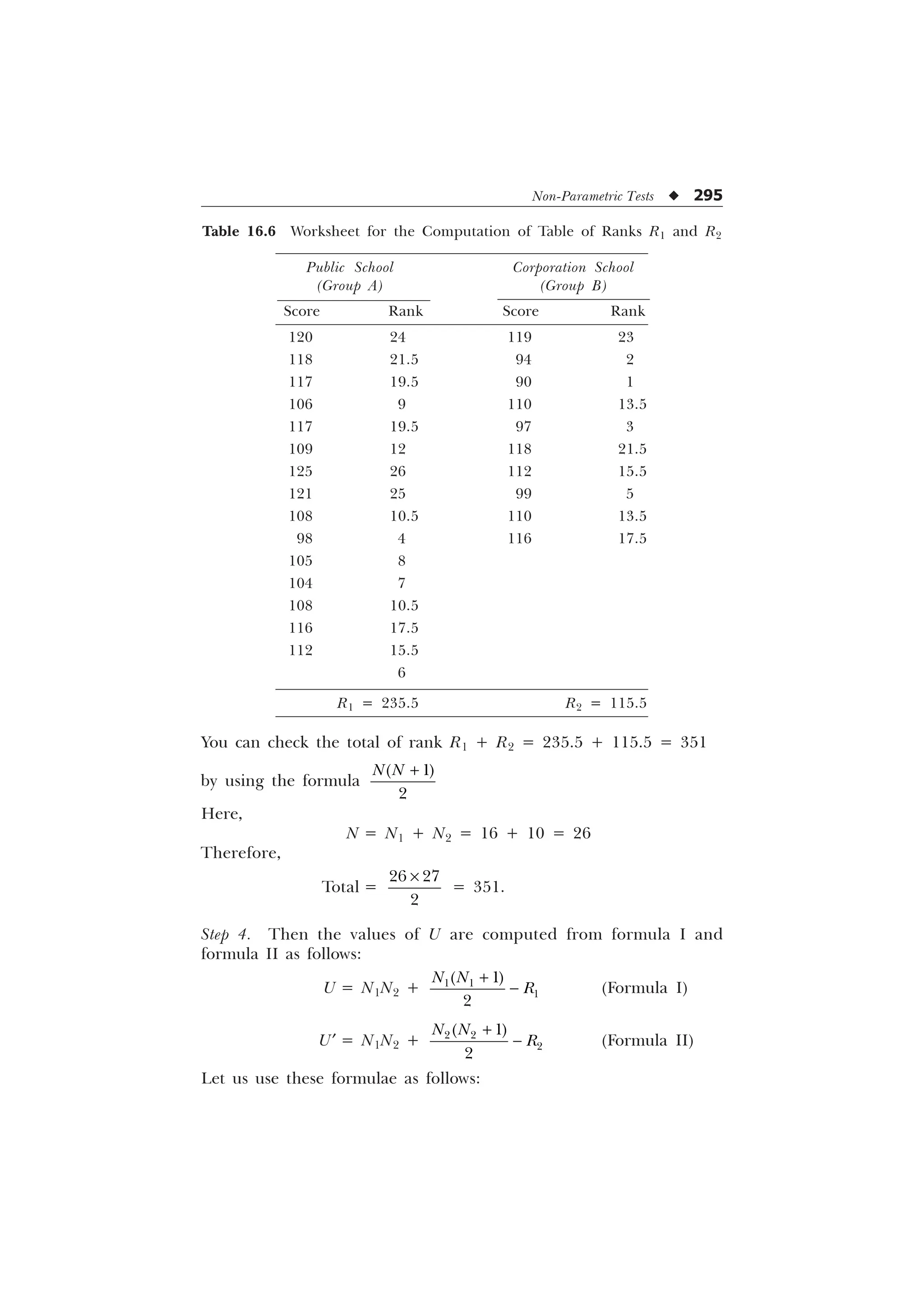

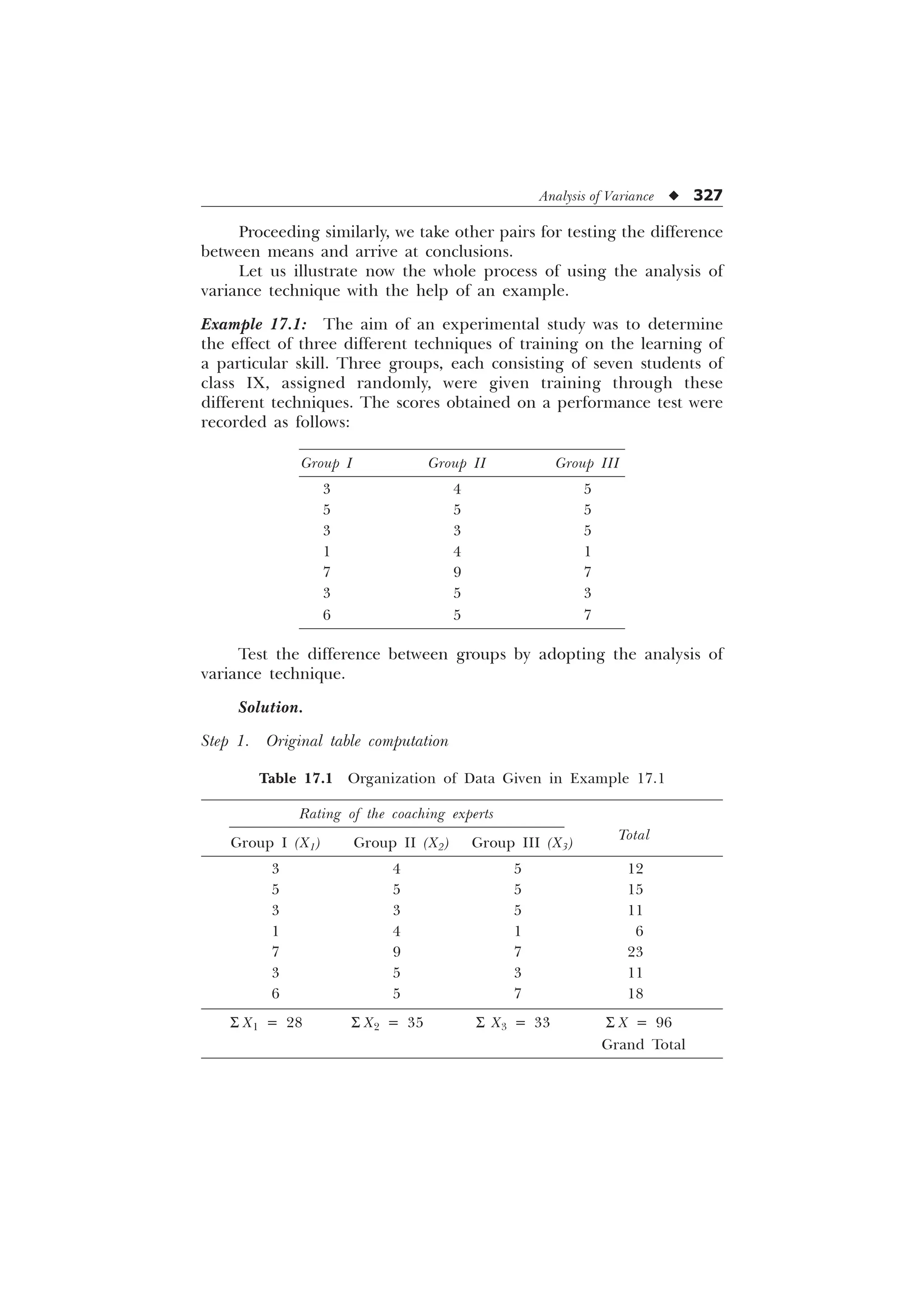

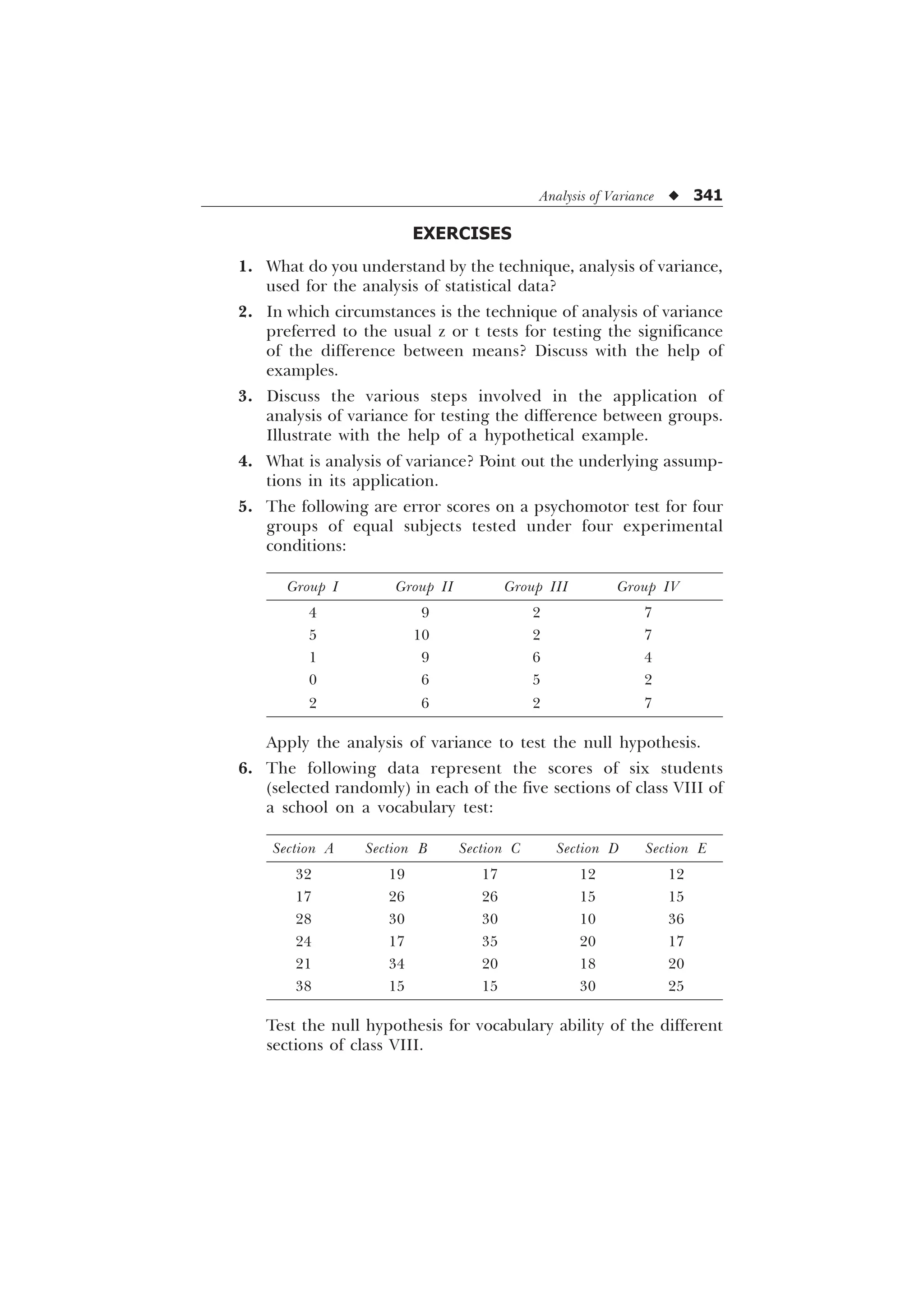

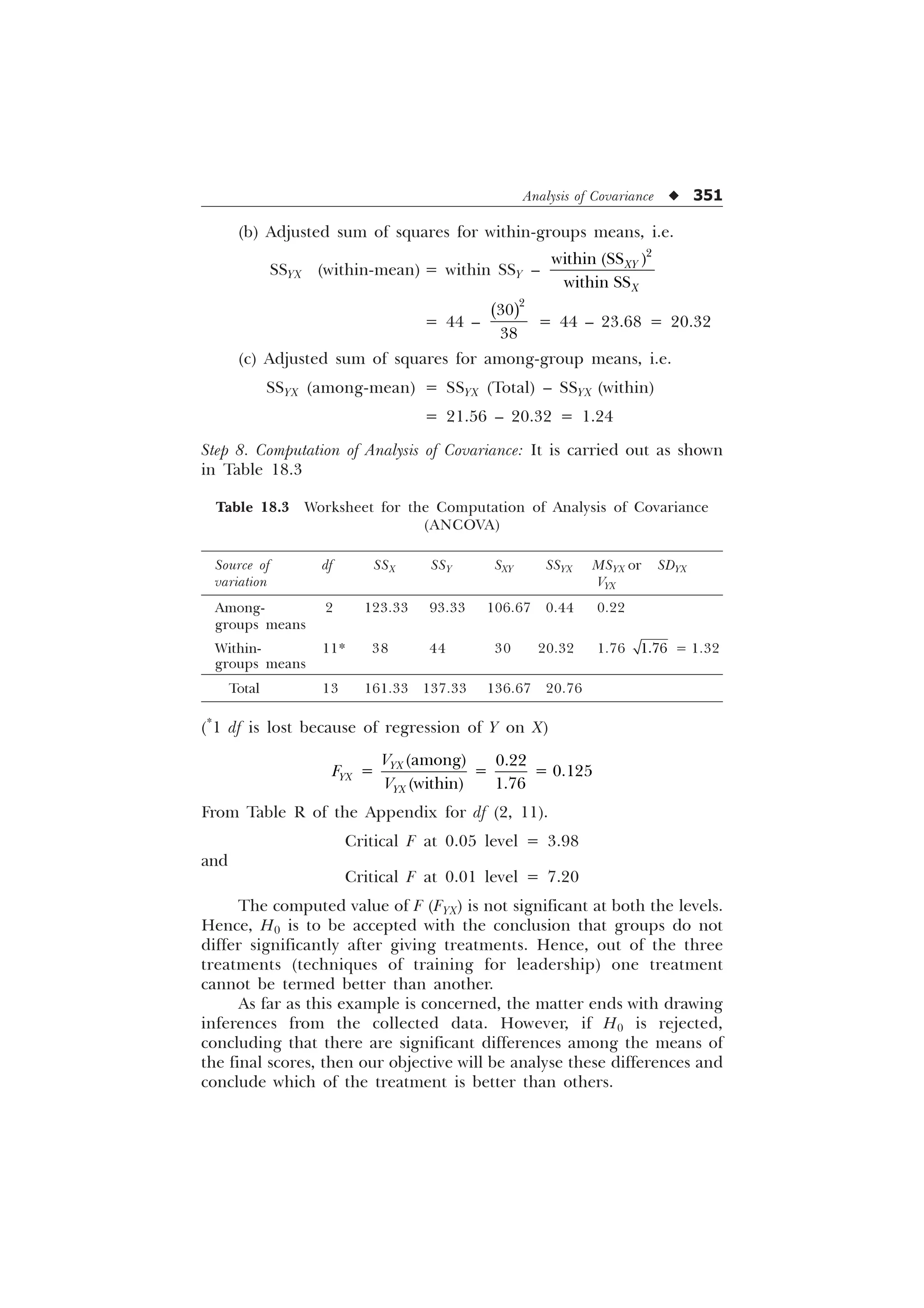

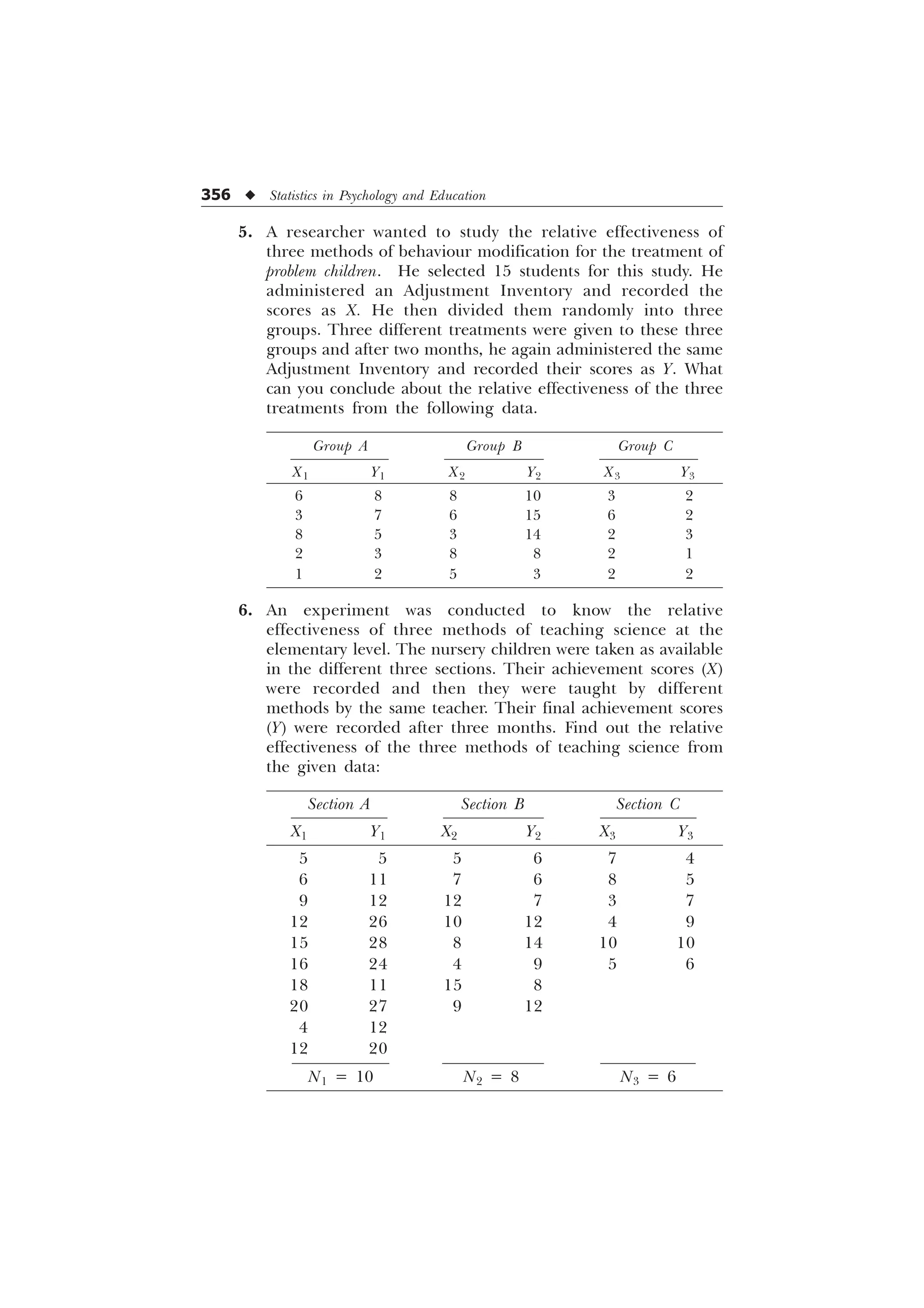

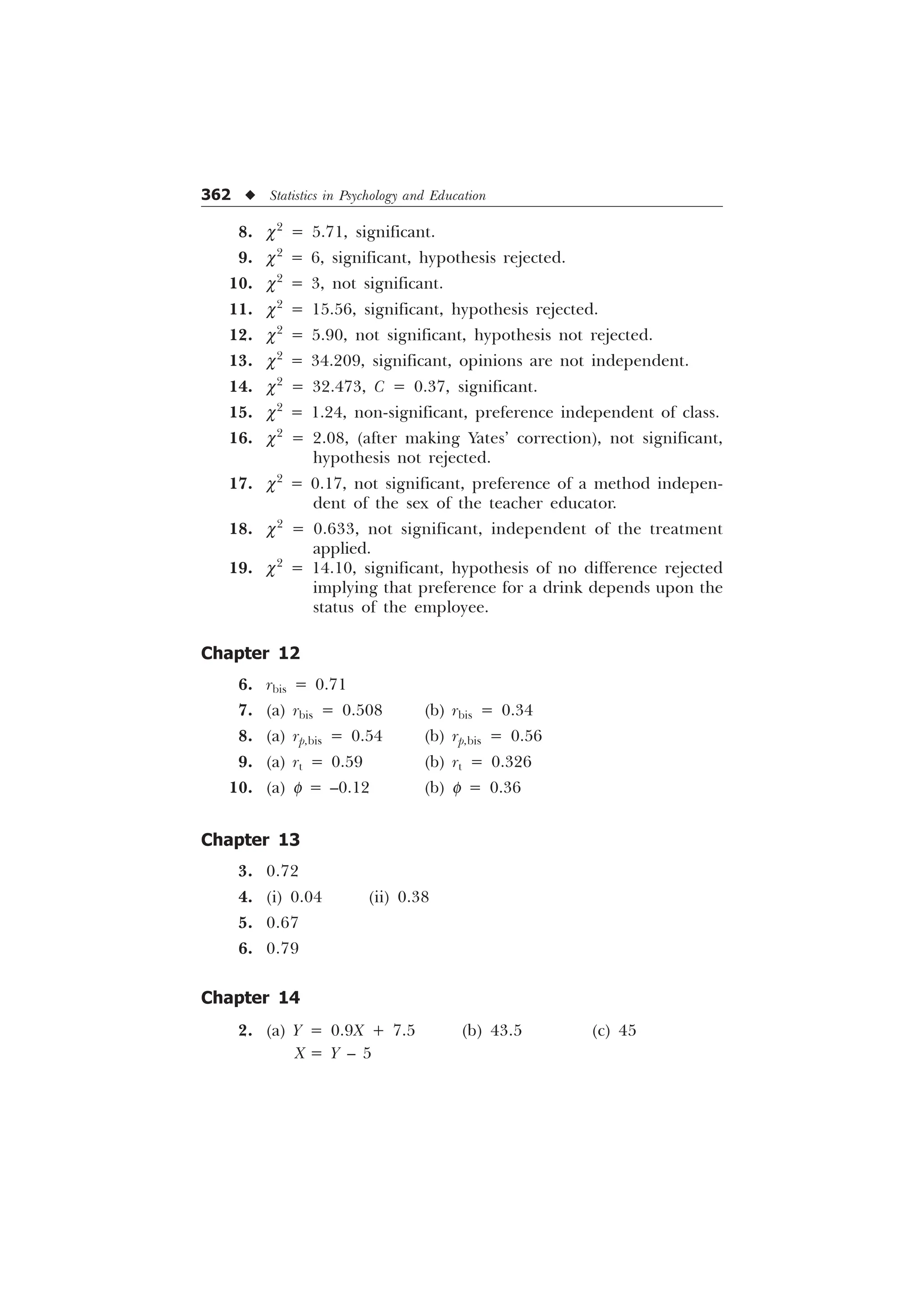

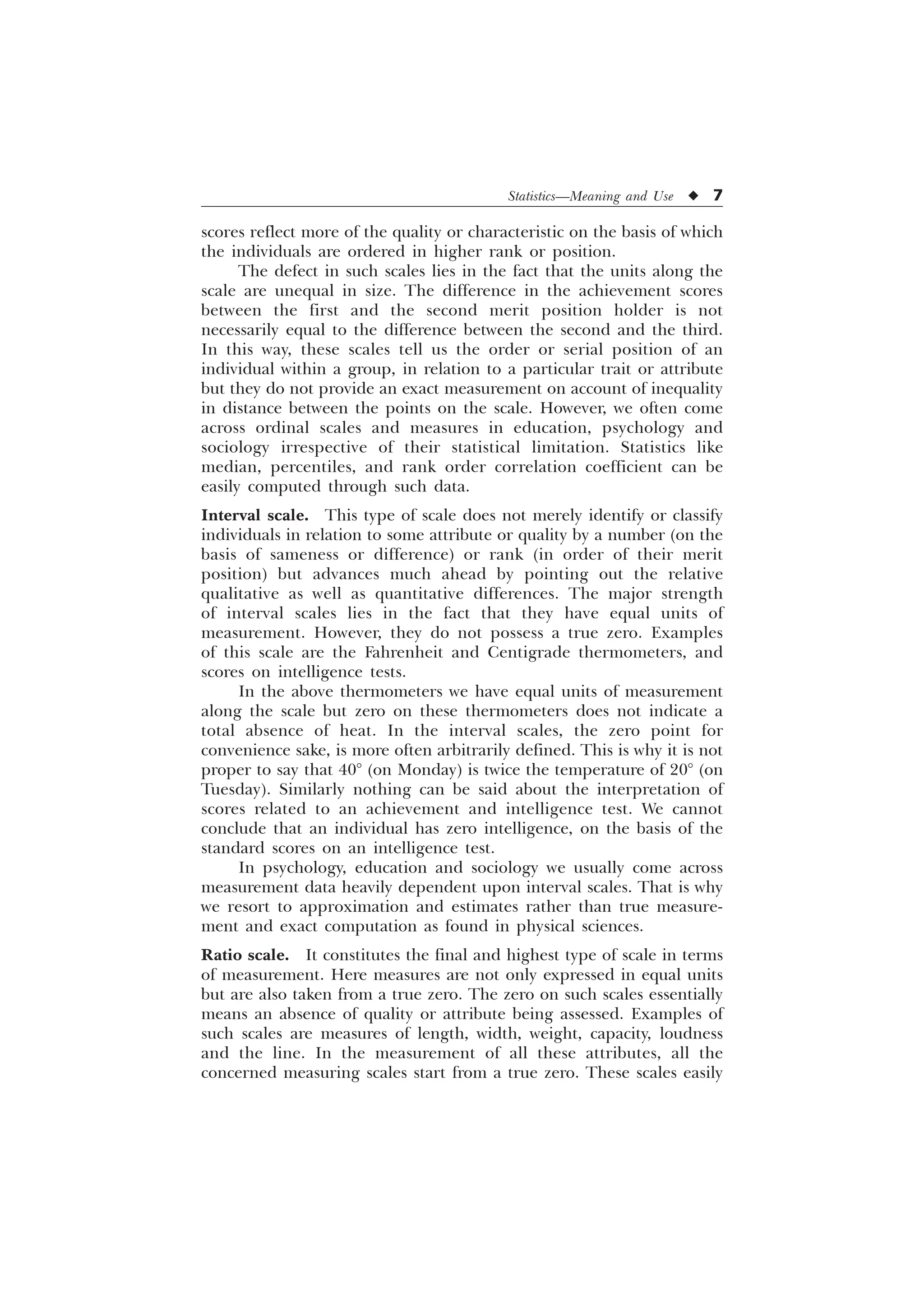

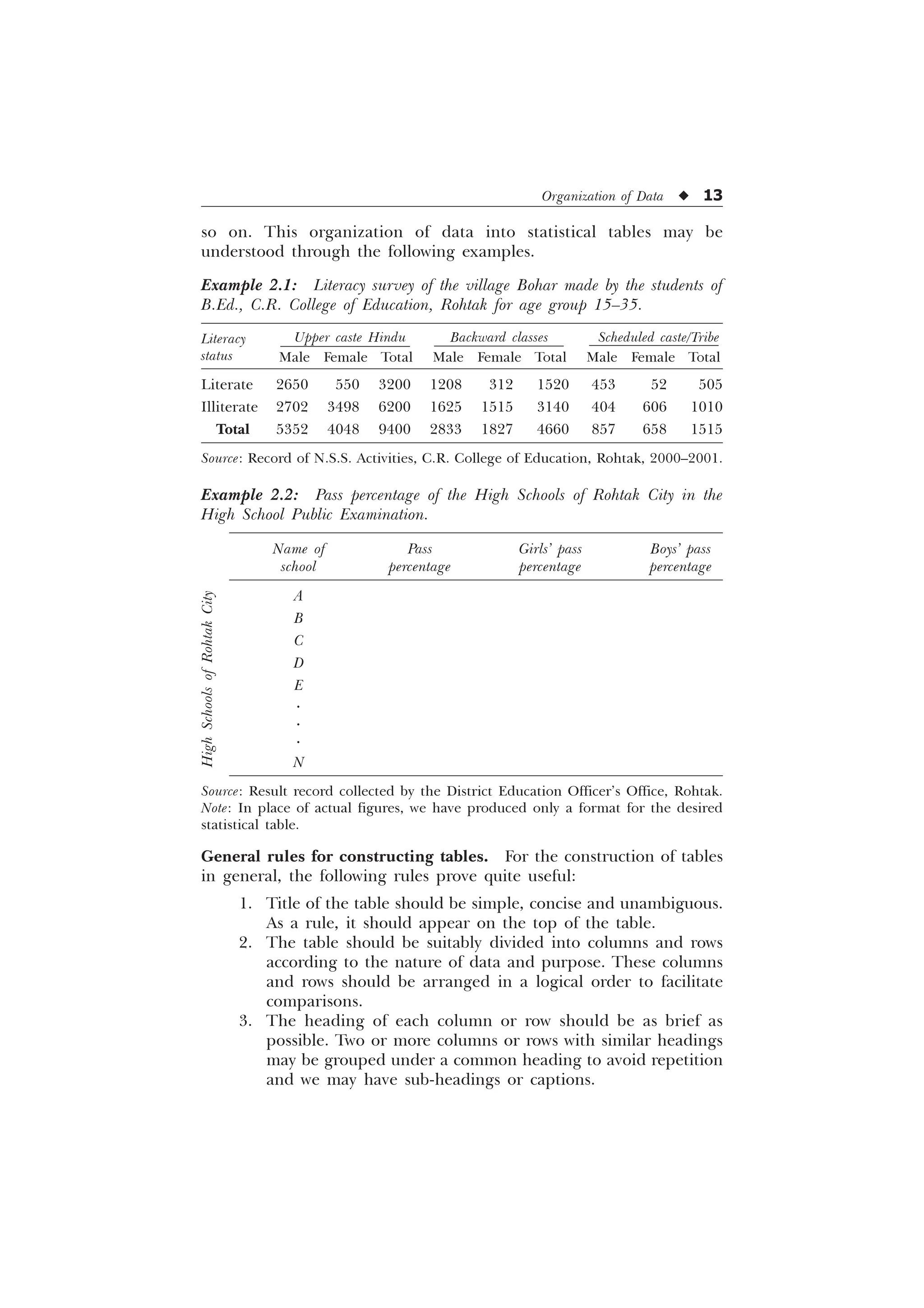

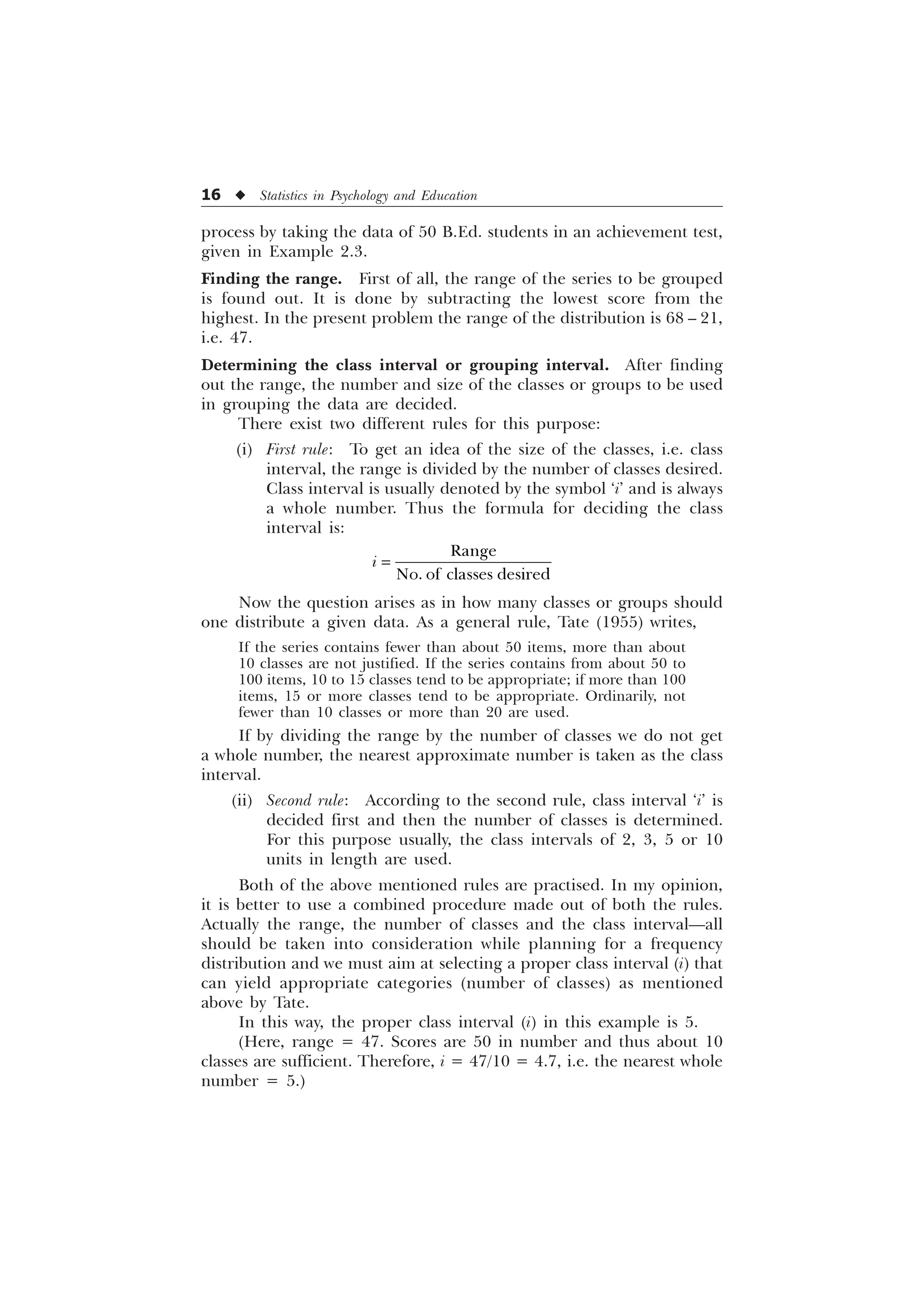

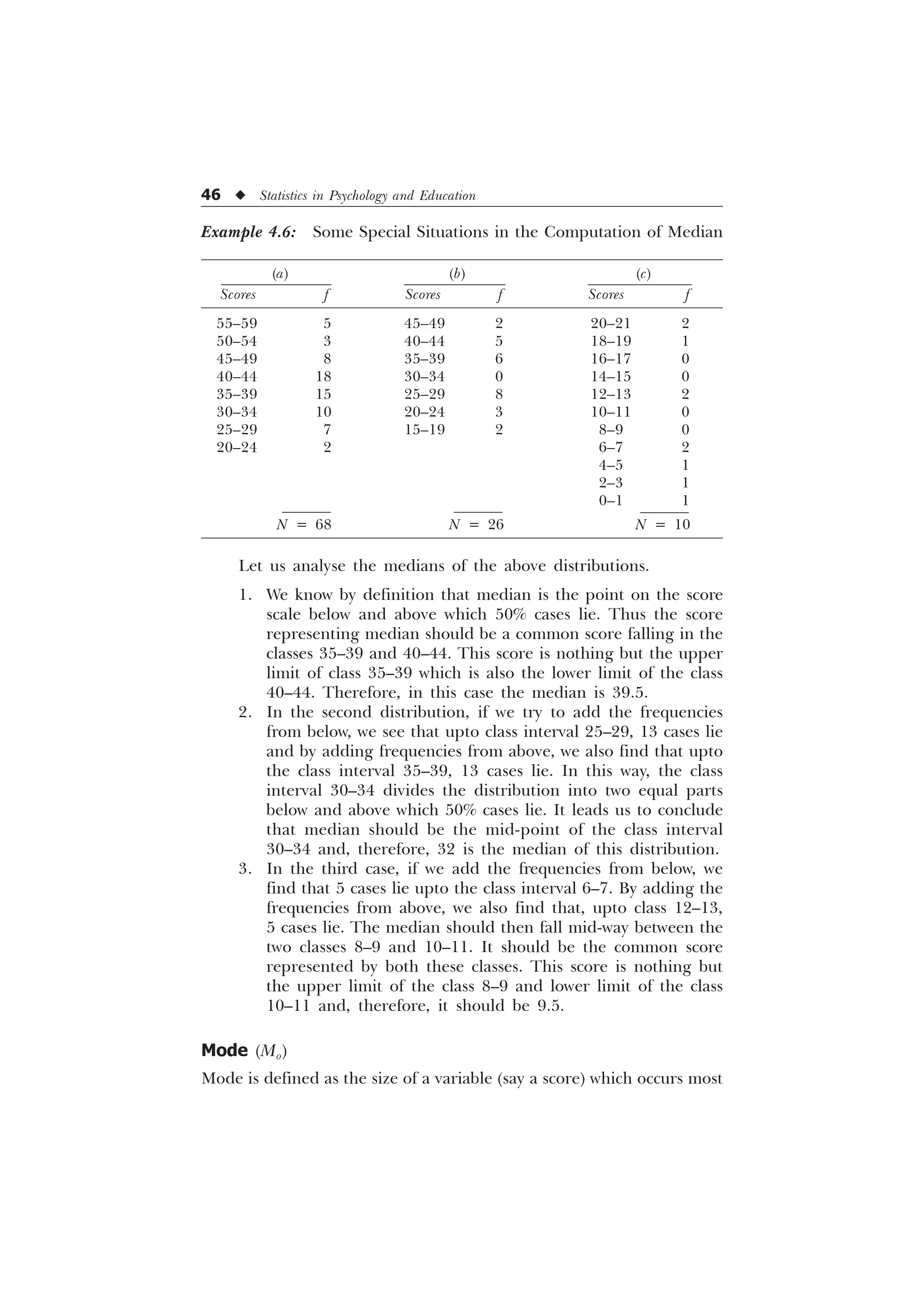

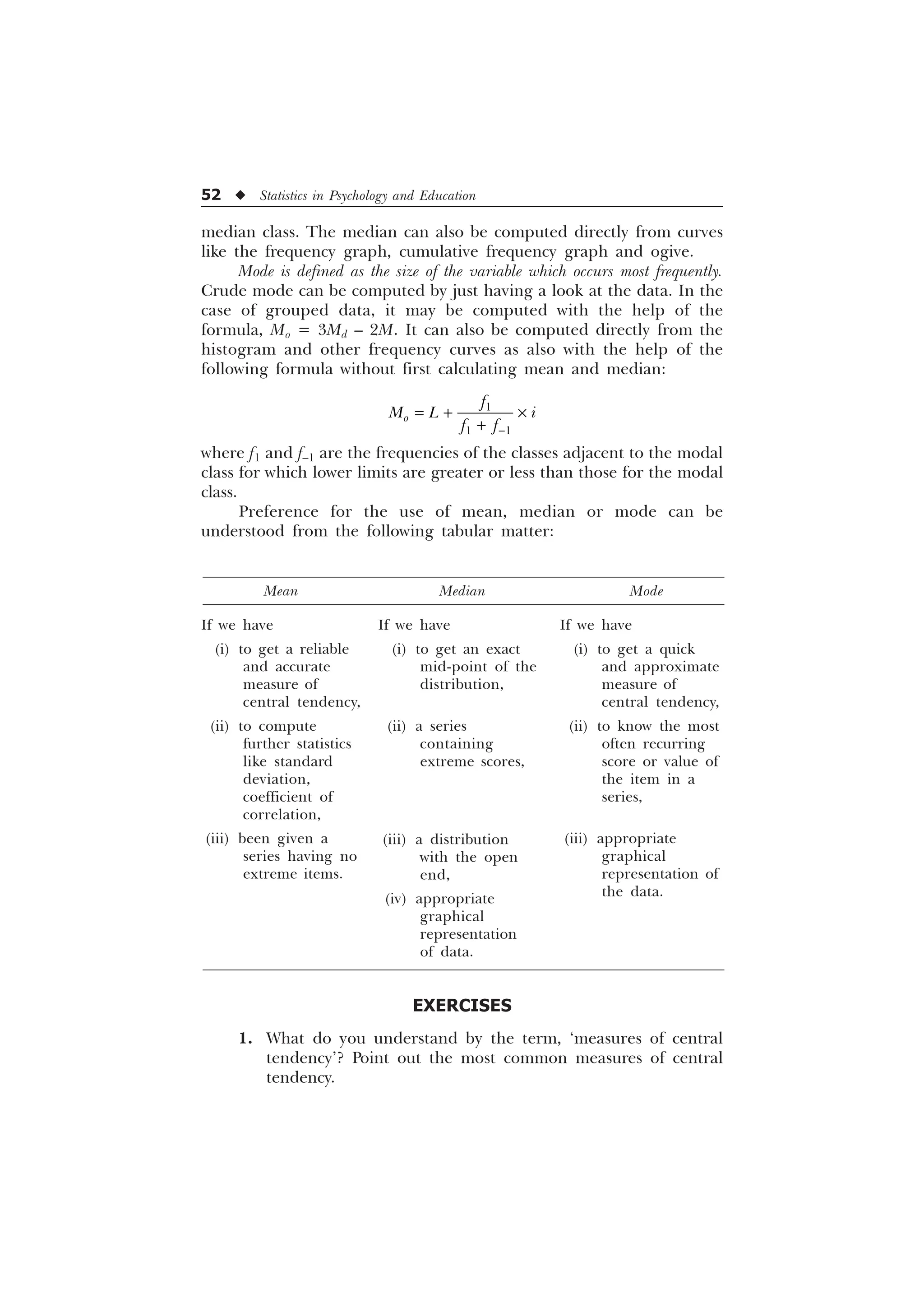

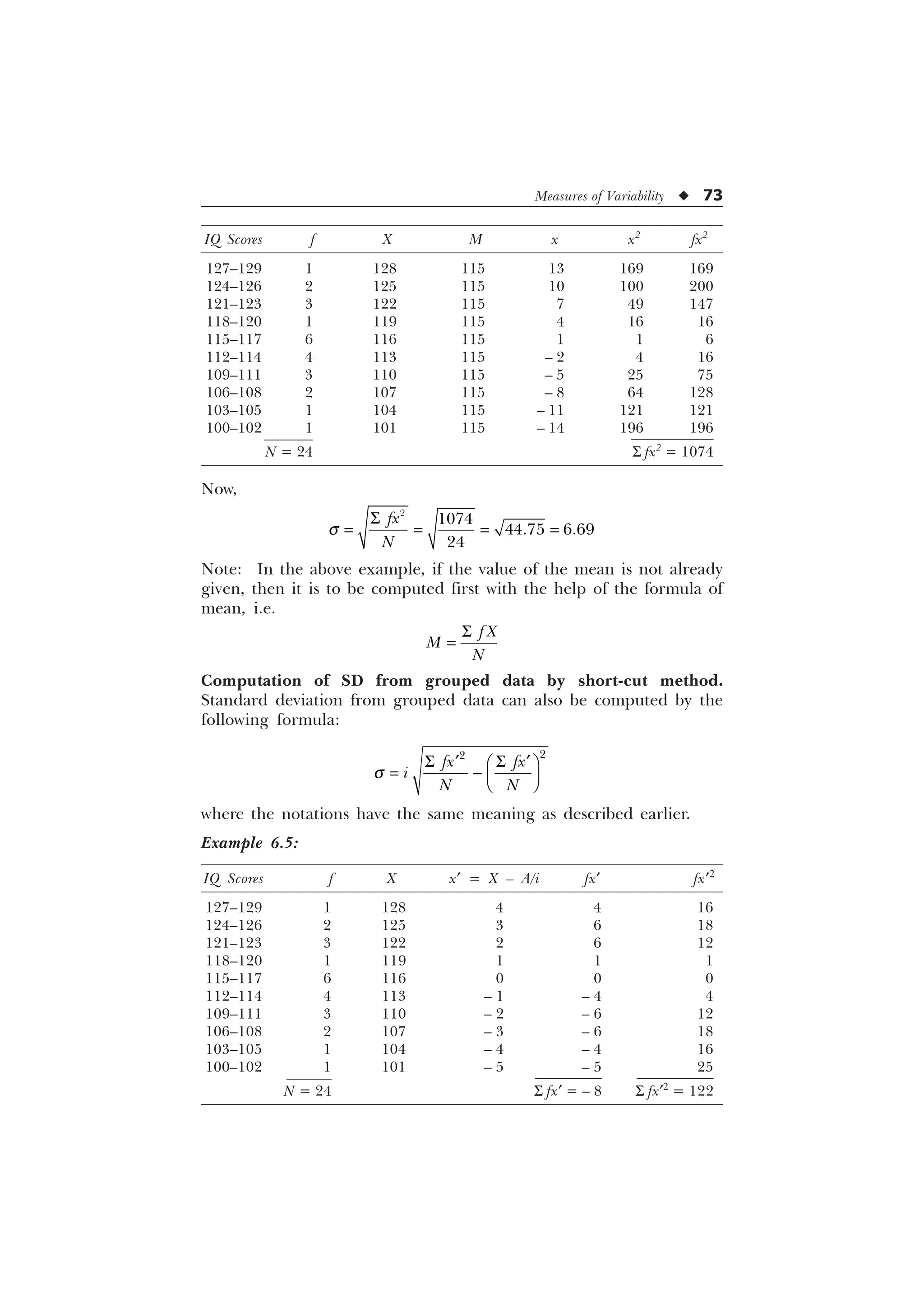

Computation of standard deviation (SD) from ungrouped data.

Standard deviation can be computed from the ungrouped scores by

the formula

T

6

[

1

The use of this formula is illustrated in the following example:

Example 6.3: Calculate SD for the following set of scores:

52, 50, 56, 68, 65, 62, 57, 70.

Solution. Mean of the given scores

M =

N = 8

Scores Deviation from the

X mean (X – M) or x x2

52 – 8 64

50 – 10 100

56 – 4 16

68 8 64

65 5 25

62 2 4

57 – 3 9

70 10 100

S x2

= 382

Formula s =

6

[

1

=

[Ans. Standard Deviation = 6.91]

Computation of SD from grouped data. Standard deviation in case

of grouped data can be computed by the formula

s =

I[

1

6

The use of the formula can be illustrated with the help of the following

example.

Example 6.4: Compute SD for the frequency distribution given below.

The mean of this distribution is 115.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/stats-s-241206101830-e3d4cc67/75/Stats-S-K-Mangal-statistics-textook-in-pdf-84-2048.jpg)

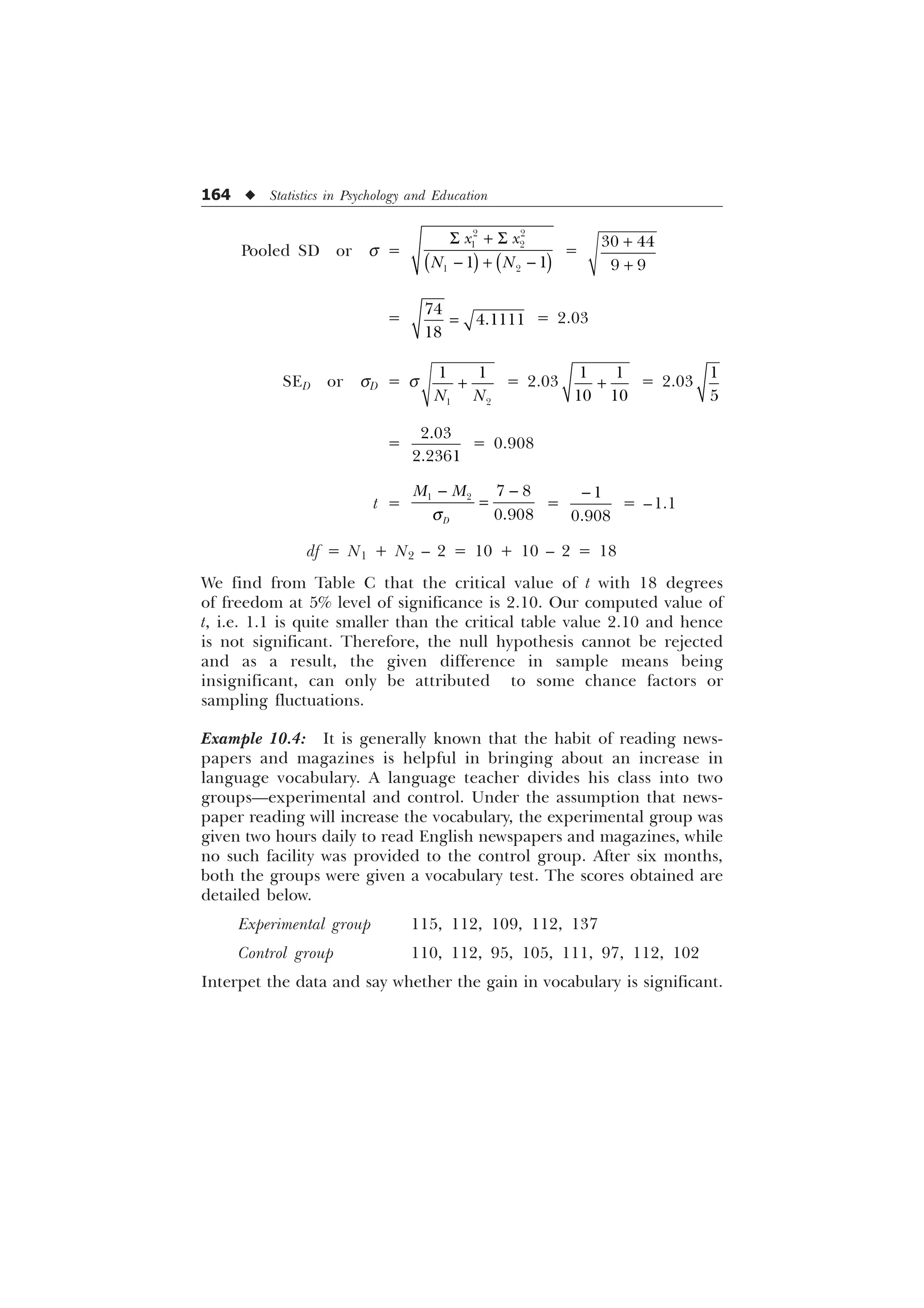

![74 u Statistics in Psychology and Education

Now putting the appropriate figures in the formula:

s =

6 6

„ „

È Ø

É Ù

Ê Ú

I[ I[

L

1 1

=

È Ø

É Ù

Ê Ú

=

–

=

–

=

= 6.69

[Ans. Standard Deviation = 6.69.]

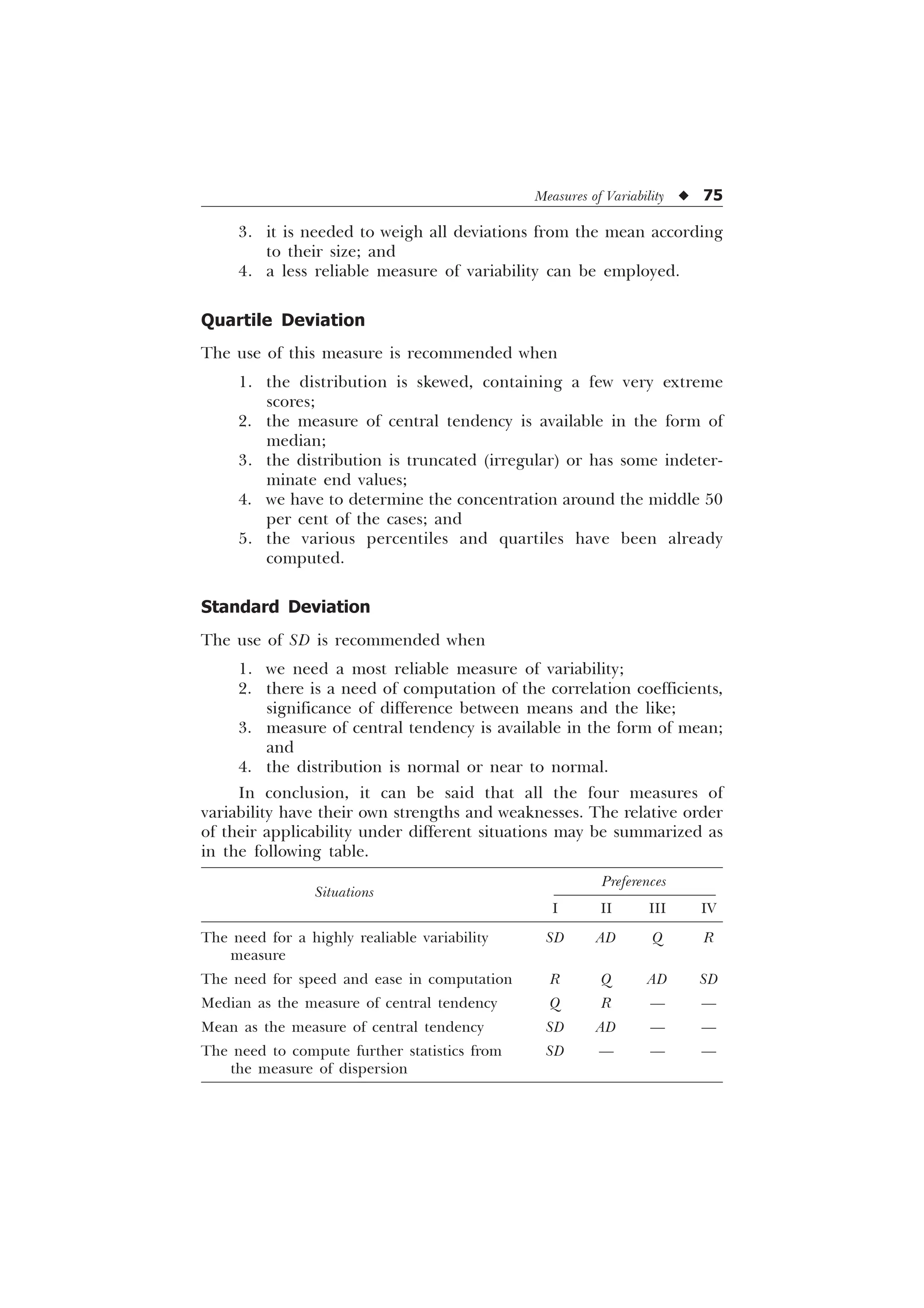

WHEN AND WHERE TO USE THE VARIOUS MEASURES OF

VARIABILITY

Range

The computation of this measure of variability is recommended when

1. we need to know simply the highest and lowest scores of the

total spread;

2. the group or distribution is too small;

3. we want to know about the variability within the group within

no time;

4. we require speed and ease in the computation of a measure of

variability; and

5. the distribution of the scores of the group is such that the

computation of other measures of variability is not much

useful.

Average Deviation

This measure is to be used when

1. distribution of the scores is normal or near to normal;

2. the standard deviation is unduly influenced by the presence of

extreme deviations;](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/stats-s-241206101830-e3d4cc67/75/Stats-S-K-Mangal-statistics-textook-in-pdf-86-2048.jpg)

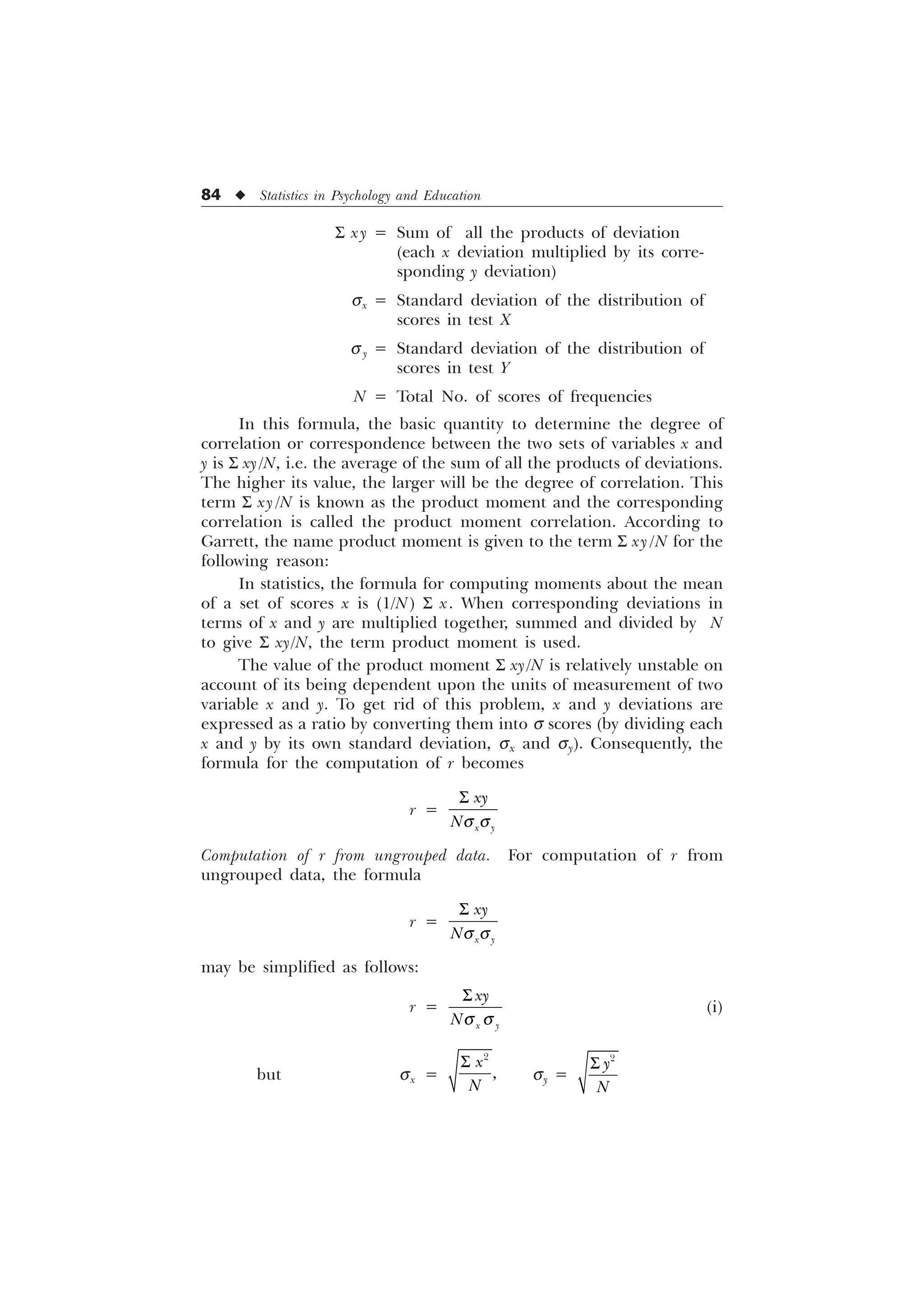

![Linear Correlation u 81

17, 25, 9, 35, 18, we will rank them as 4, 2, 5, 1 and 3. We determine

the ranks or the positions of the individuals in both the given sets of

scores. These ranks are then subjected to further calculation for the

determination of the coefficient of correlation.

How is it done can be understood through the following

examples.

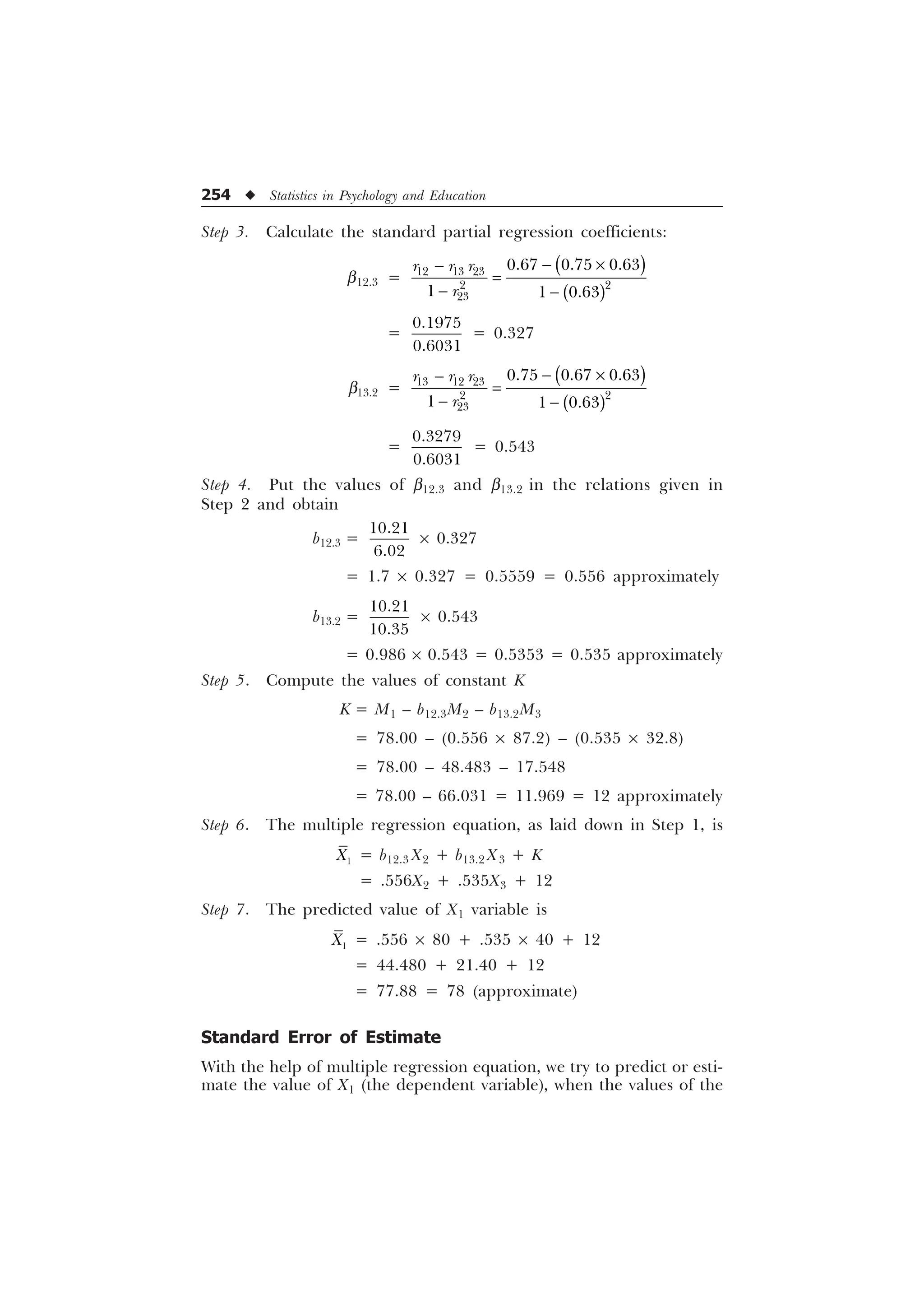

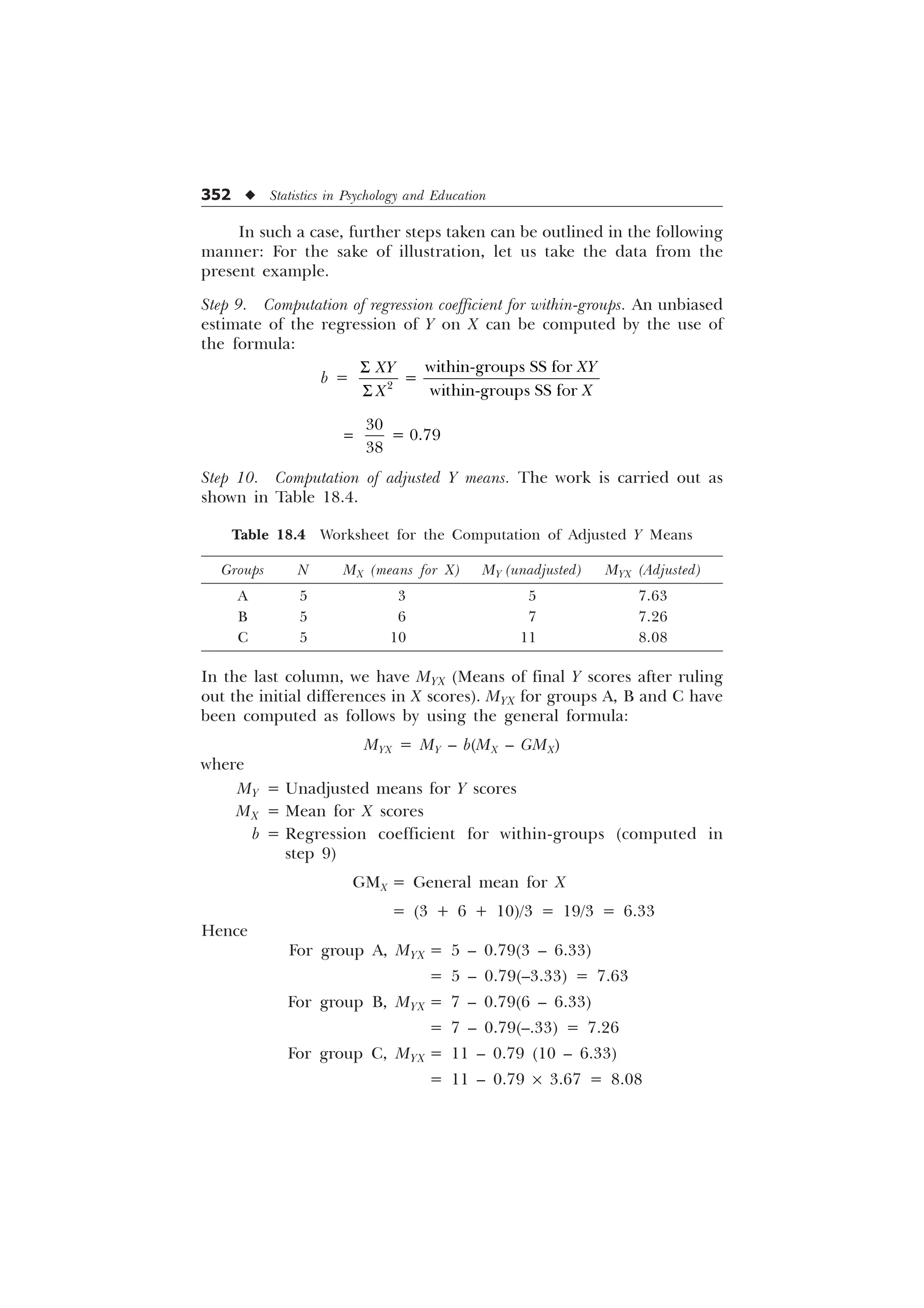

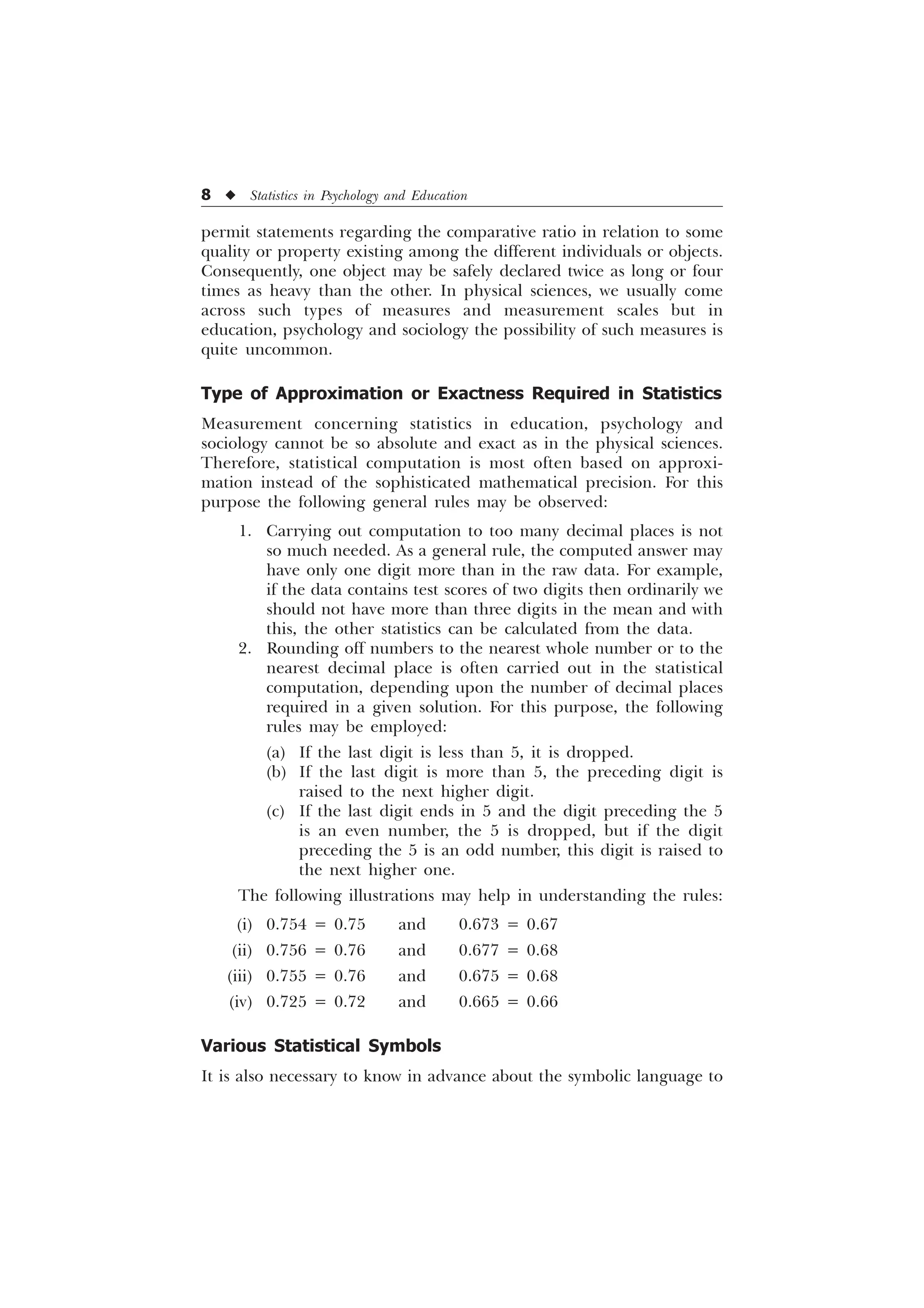

Example 7.1

Marks in Marks in Rank in Rank in Difference Difference

Individuals History Civics History Civics in ranks, squared

(X) (Y) (R1) (R2) irrespespective (d2

)

of

+ve or –ve signs

(R1 – R2 = |d|)

A 80 82 2 3 1 1

B 45 86 11 2 9 81

C 55 50 10 10 0 0

D 56 48 9 11 2 4

E 58 60 8 9 1 1

F 60 62 7 8 1 1

G 65 64 6 7 1 1

H 68 65 5 6 1 1

I 70 70 4 5 1 1

J 75 74 3 4 1 1

K 85 90 1 1 0 0

N = 11 S d2

= 92

r =

G

1 1

6

=

– –

–

=

= 0.58

[Ans. Rank correlation coefficient = 0.58.]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/stats-s-241206101830-e3d4cc67/75/Stats-S-K-Mangal-statistics-textook-in-pdf-93-2048.jpg)

![82 u Statistics in Psychology and Education

Example 7.2

Scores Scores Rank in X Rank in Y |R1 – R2|

Individuals in test in test (R1) (R2) = |d|

(X) (Y) d2

A 12 21 8 6 2 4

B 15 25 6.5 3.5 3 9

C 24 35 2 2 0 0

D 20 24 4 5 1 1

E 8 16 10 9 1 1

F 15 18 6.5 8 0.5 0.25

G 20 25 4 3.5 0.5 0.25

H 20 16 4 9 5 25

I 11 16 9 9 0 0

J 26 38 1 1 0 0

N = 10 S d2

= 40.5

r =

6

G

1 1

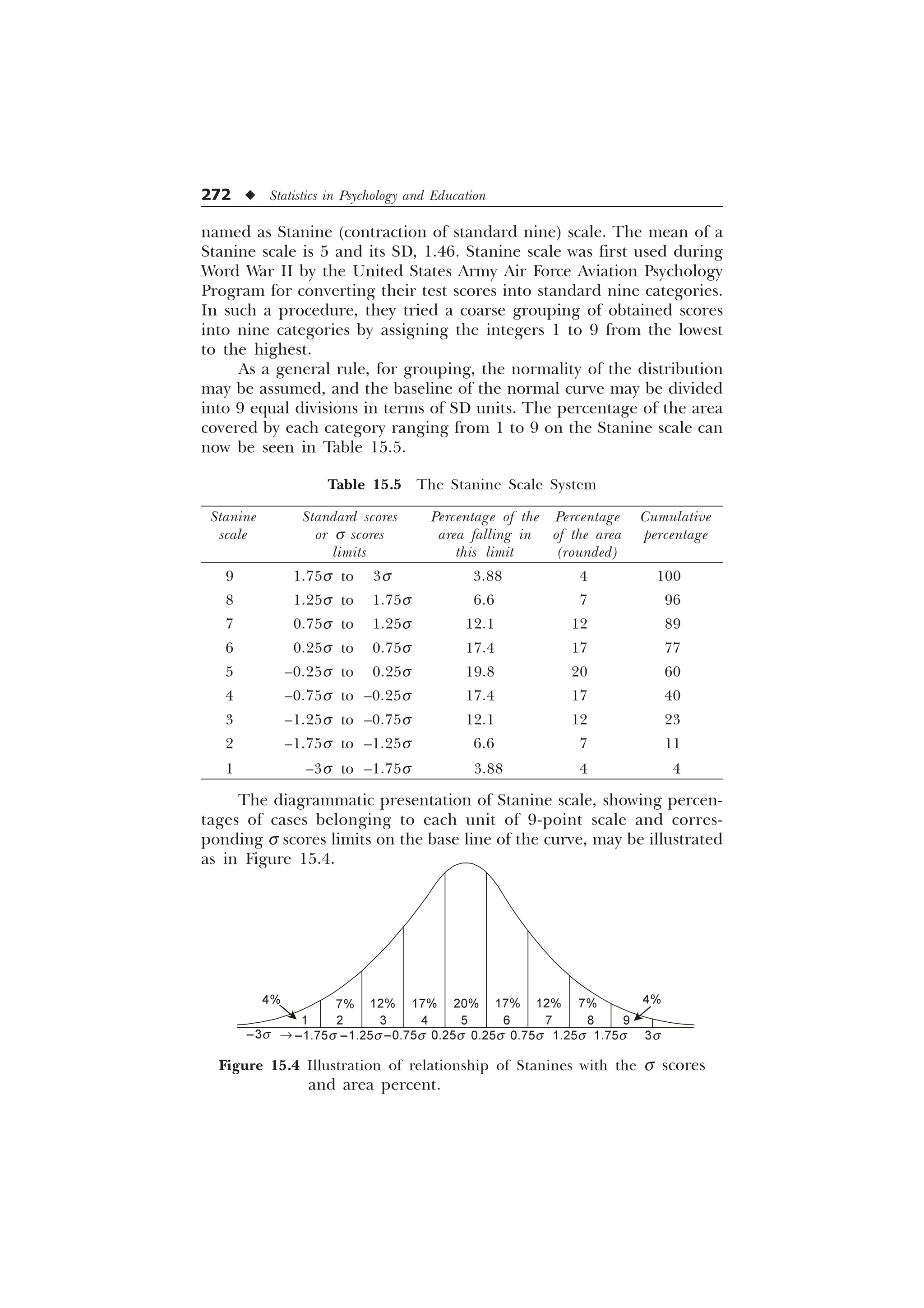

=

–

=

–

–

=

= 0.755

[Ans. Rank correlation coefficient = 0.755.]

Steps for the calculation of r:

Step 1. First, a position or a rank is assigned to each individual on

both the tests. These ranks are put under column 3 (designated R1)

and column 4 (designated R2), respectively. The task of assigning ranks,

as in Example 1, is not difficult. But as in Example 2, where two or

more individuals are found to have achieved the same score, some

difficulty arises. In this example, in the first test, X, B and F are two

individuals who have the same score, i.e. 15. Therefore, score 15

occupies the 6th position in order of merit. But now the question arises

as to which one of the two individuals B and F should be ranked 6th

or 7th. In order to overcome this difficulty we share the 6th and 7th

rank equally between them and thus rank each one of them as 6.5.

Similarly, if there are three persons who have the same score and

share the same rank, we take the average of the ranks claimed by these

persons. For example, we can take score 20 in Example 2 which is](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/stats-s-241206101830-e3d4cc67/75/Stats-S-K-Mangal-statistics-textook-in-pdf-94-2048.jpg)

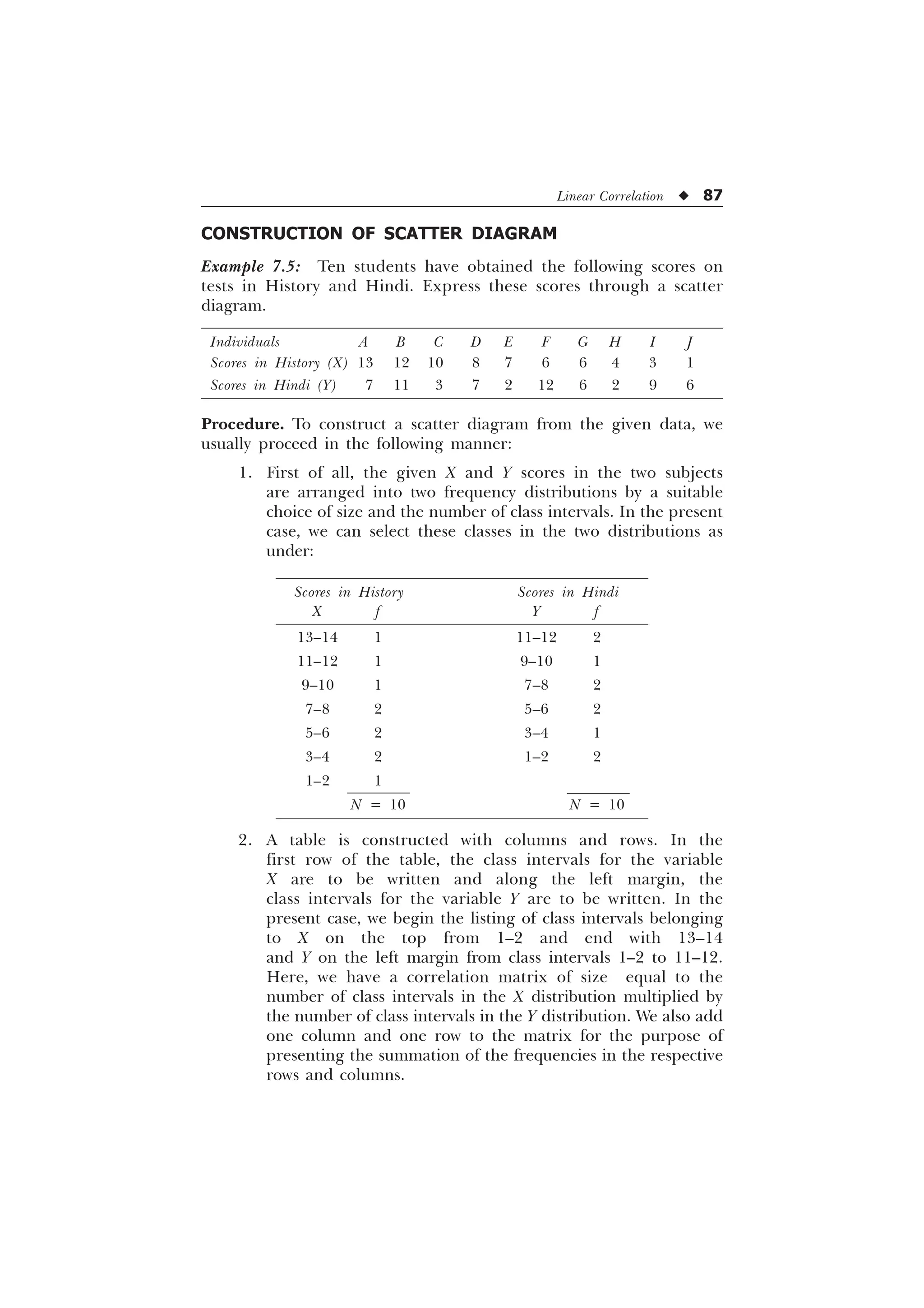

![Linear Correlation u 85

Substituting these values of sx and sy in (i) we get

r =

6 6

6 6 6 6

[ [

[ [

1

1 1

(ii)

The use of this formula may be illustrated through the following

example:

Example 7.3

Individuals Scores in test Scores in test

X Y x y xy x2

y2

A 15 60 –10 10 –100 100 100

B 25 70 0 20 0 0 400

C 20 40 –5 –10 50 25 100

D 30 50 5 0 0 25 0

E 35 30 10 –20 –200 100 400

S xy S x2

S y2

= – 250 = 250 = 1000

Mean of series X, MX = 25

Mean of series Y, MY = 50

r =

6

–

6 6

[

[

=

=

1

0.5

2

[Ans. Product moment correlation coefficient = –0.5.]

Computation of r directly from raw scores when deviations are taken from zero

(without calculating deviation from the means). In this case, product

moment r is to be computed by the following formula:

6 6 6

Ë Û Ë Û

6 6 6 6

Í Ý Í Ý

1 ; ;

U

1 ; ; 1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/stats-s-241206101830-e3d4cc67/75/Stats-S-K-Mangal-statistics-textook-in-pdf-97-2048.jpg)

![86 u Statistics in Psychology and Education

where

X and Y = Raw scores in the test X and Y.

XY = Sum of the products of each X score multiplied with

its corresponding Y score

N = Total No. of cases or scores

The use of this formula may be understood through the following

example:

Example 7.4

Scores in Scores in

Subject test X test Y XY X2

Y2

A 5 12 60 25 144

B 3 15 45 9 225

C 2 11 22 4 121

D 8 10 80 64 100

E 6 18 108 36 324

N = 5 S X = 24 S Y = 66 S XY = 315 S X2

= 138 S Y2

= 914

r =

6 6 6

Ë Û Ë Û

6 6 6 6

Í Ý Í Ý

1 ; ;

1 ; ; 1

Here,

r =

– –

– – –

=

=

–

=

[Ans. Product moment correlation coefficient = –0.48.]

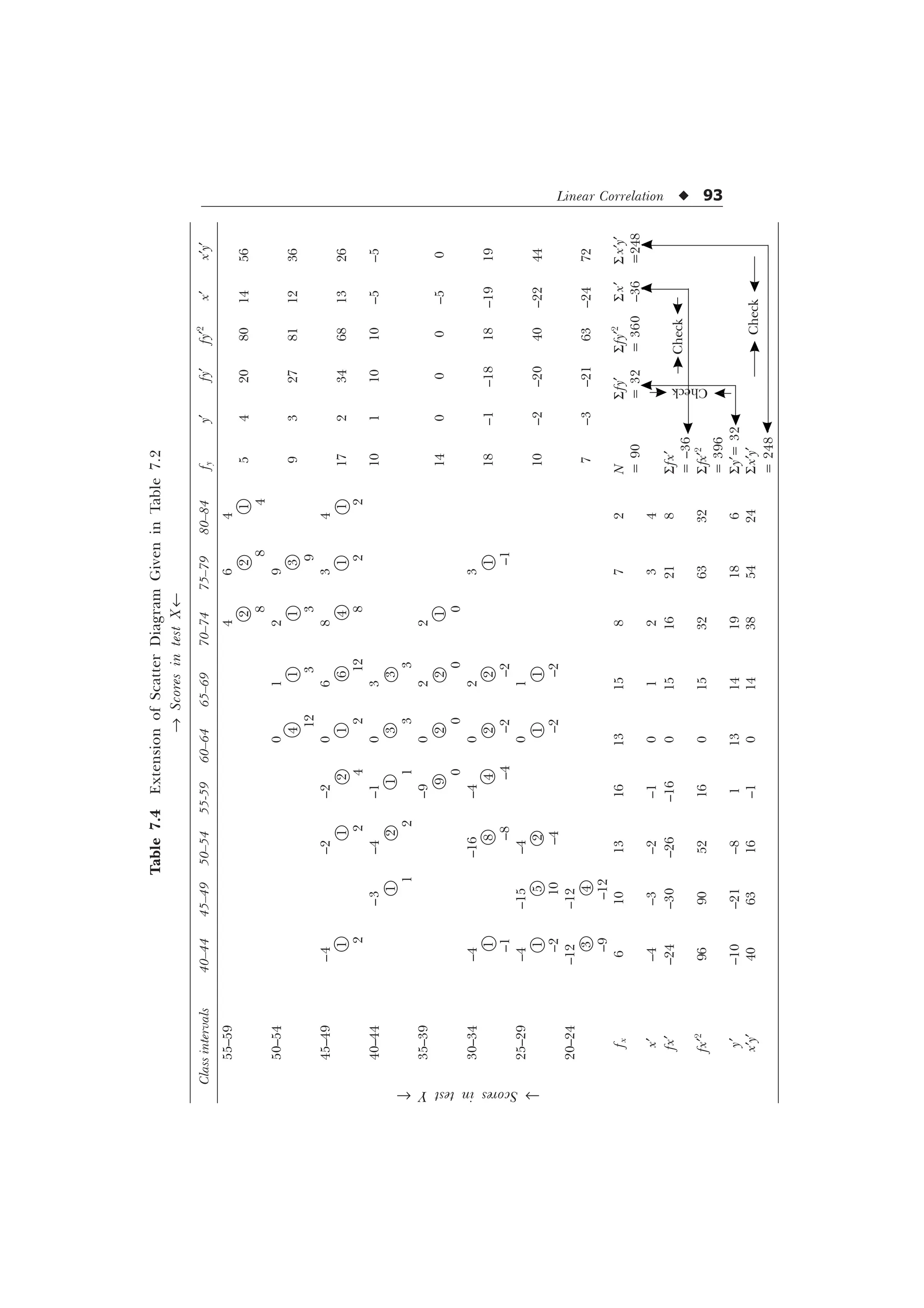

Computation of product moment r with the help of a scatter diagram or

correlation table. Product moment r may be computed through a scatter

diagram or correlation table. If this diagram or table is not given, then

the need of its construction arises. Let us illustrate the construction of

a scatter diagram or a correlation table with the help of some hypo-

thetical data.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/stats-s-241206101830-e3d4cc67/75/Stats-S-K-Mangal-statistics-textook-in-pdf-98-2048.jpg)

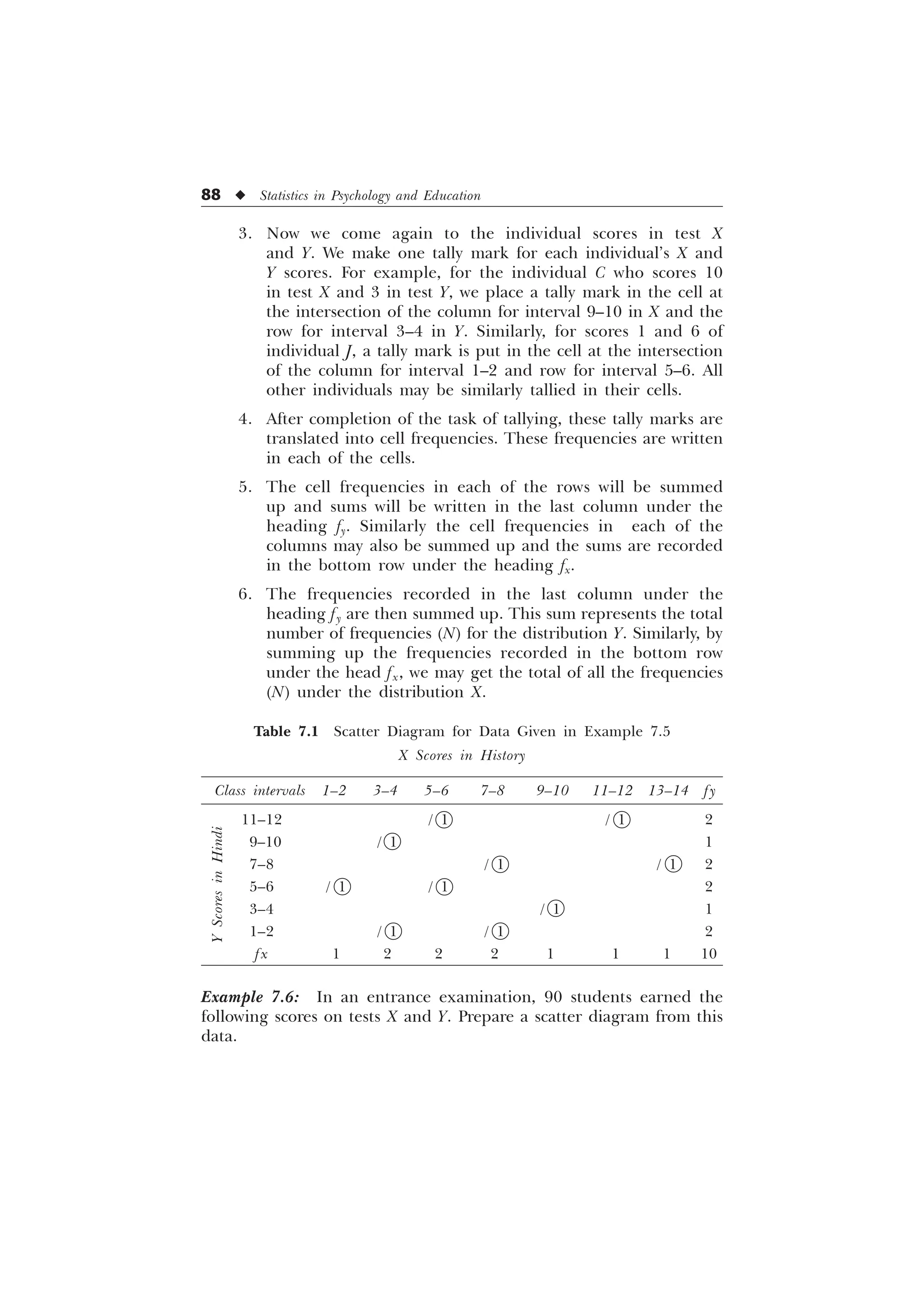

![Linear Correlation u 91

Computation of r

We know that the gereral formula for computing r is

T T

6

[

[

U

1

Here x and y denote the deviations of X and Y scores from their

respective means. When we take deviations from the assumed means of

the two distributions, this formula is likely to be changed to the one

below:

r =

6 6 6

„ „ „ „

Ë Û Ë Û

6 6 6 6

„ „ „ „

Í Ý Í Ý

1 [ I [ I

1 I [ I [ 1 I I

It may be observed that in computing r by the above formula, we need

to know the values of S x¢ y¢, S fx¢, S fy¢, S fx¢2

and S fy¢2

. All these values

may be conveniently computed through a scatter diagram. The process

of determining these is illustrated through the extension of scatter

diagrams constructed in Tables 7.1 and 7.2.

Now just look into the Table 7.3, here we can get the values

S x¢ y¢ = 5, S fx¢ = –3, S fy¢ = 5

S fx¢2

= 33, S fy¢2

= 33

Putting these values in the formula for computing r, we get

r =

–

– –

Ë ÛË Û

Í ÝÍ Ý

=

Ë Û

Ë Û

Í Ý

Í Ý

=

–

=

=

= 0.207

= 0.21 (approx.)

[Ans. Product moment coefficient of correlation = 0.21.]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/stats-s-241206101830-e3d4cc67/75/Stats-S-K-Mangal-statistics-textook-in-pdf-103-2048.jpg)

![94 u Statistics in Psychology and Education

Now putting the relevant values in the formula, we get

r =

6 6 6

„ „ „ „

Ë Û Ë Û

6 6 6 6

„ „ „ „

Í Ý Í Ý

1 [ I [ I

1 I [ I [ 1 I I

=

– –

Ë ÛË Û

– – – –

Í ÝÍ Ý

=

=

–

=

=

= 0.715 = 0.73 (approx).

[Ans. Pearson’s correlation coefficient = 0.73]

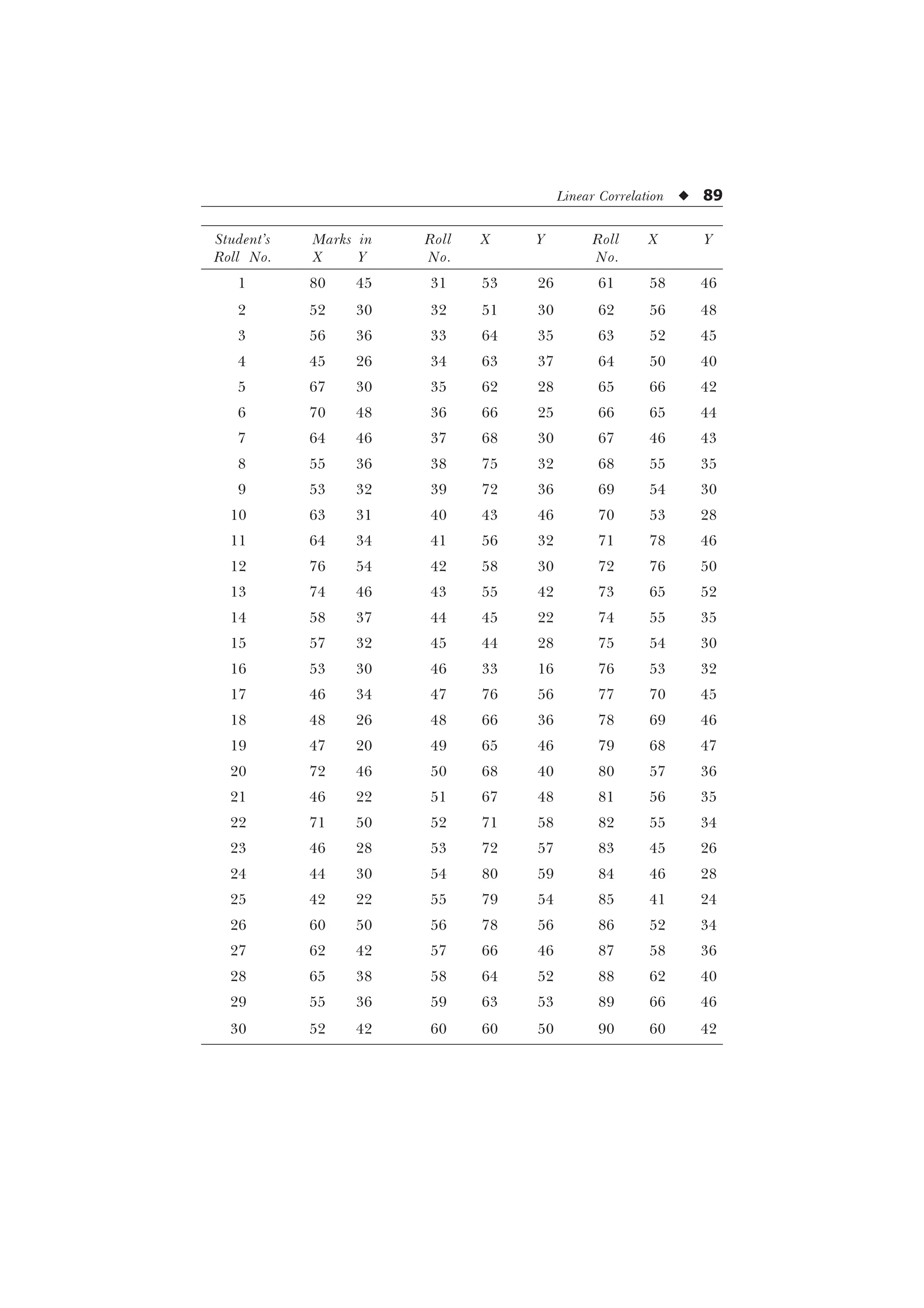

Explanation of the process of computation of r from scatter

diagrams. Let us consider the process of the computation of the

values of S fx, S fy, S fx¢2

, S fy¢2

and S x¢y¢ with the help of the scatter

diagram computed above in Tables 7.3 and 7.4 and then the

determination of r from the formula. The various steps involved are

as follows:

Step 1. (Completion of the scatter diagram). The scatter diagram in its

complete form must have one row and one column designated fx and

fy respectively for the total of the frequencies belonging to each class

interval of the scores in test X and Y. If the totals are not given (in the

assigned scatter diagram) then they are to be computed and written in

the row and column headed by fx and fy. The grand total of these rows

and columns should tally with each other. There grand totals were 10

and 90 respectively in our problem.

Step 2. (Extension of the scatter diagram). The scatter diagram is now

extended by 5 columns designated y¢, f y¢, fy¢2

, x¢ and x¢y¢ and 5 rows

designated x¢, fx¢, fx¢2

, y¢, and x¢y¢. At the end of each of these columns

and rows, the provision for the sum (S values) is also to be kept.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/stats-s-241206101830-e3d4cc67/75/Stats-S-K-Mangal-statistics-textook-in-pdf-106-2048.jpg)

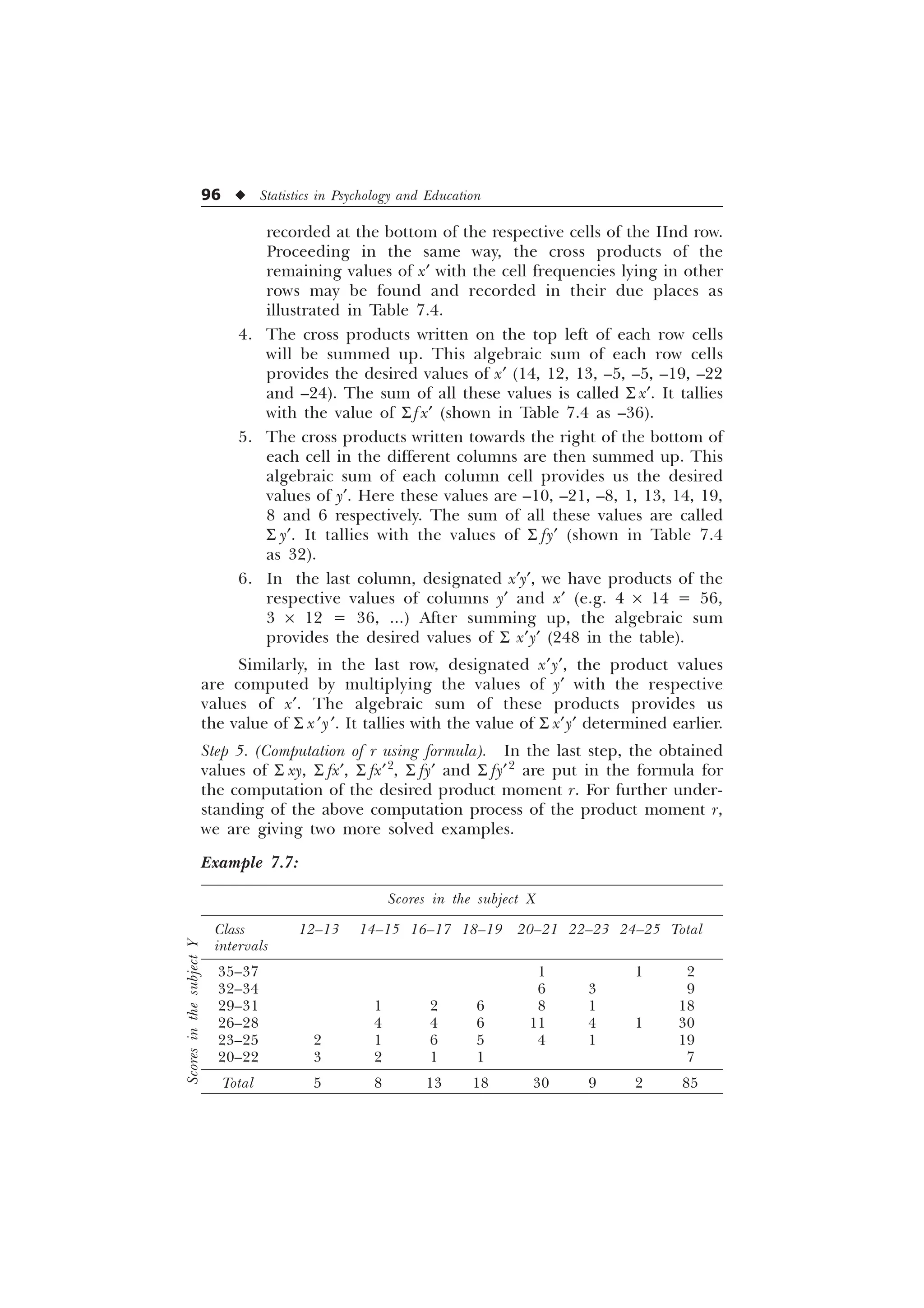

![Linear Correlation u 97

Solution: For solving the above given problem we will first work

for the extension of correlation table of the Example 7.7 and then

calculate the needed values of S x¢y¢, S fx¢, S fy¢, S fx¢2

, S fy¢2

etc. finally

for computing r. The extended table with the needed computation

work has been shown in Table 7.5.

Computation of r

r =

1 [ I [ I

1 I [ I [ 1 I I

6 6 ¹ 6

„ „ „ „

Ë Û Ë Û

6 6 6 6

„ „ „ „

Í Ý Í Ý

=

– –

– – – –

=

=

–

=

=

= 0.54 (approx.)

[Ans. Pearson’s correlation coefficient = 0.54.]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/stats-s-241206101830-e3d4cc67/75/Stats-S-K-Mangal-statistics-textook-in-pdf-109-2048.jpg)

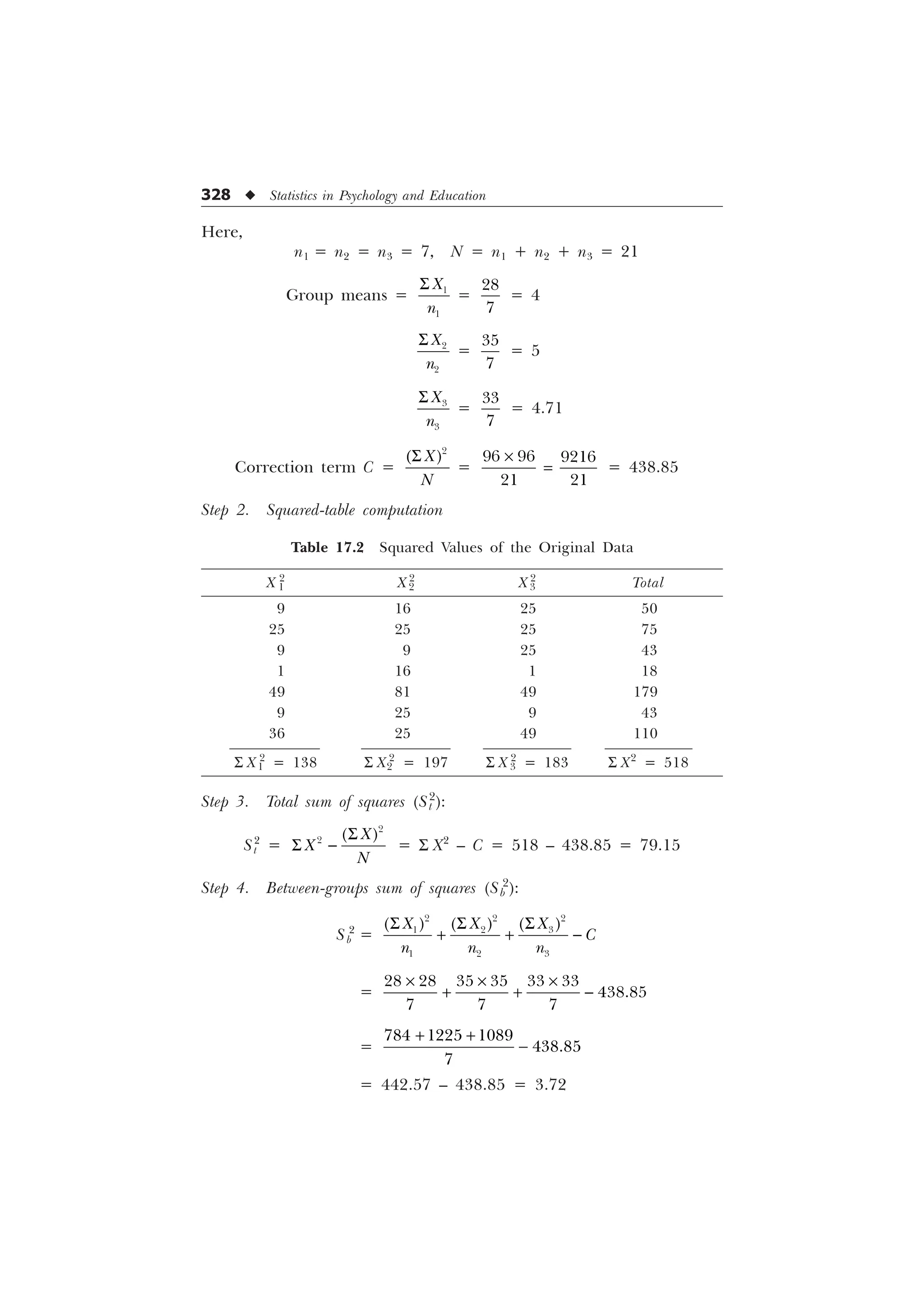

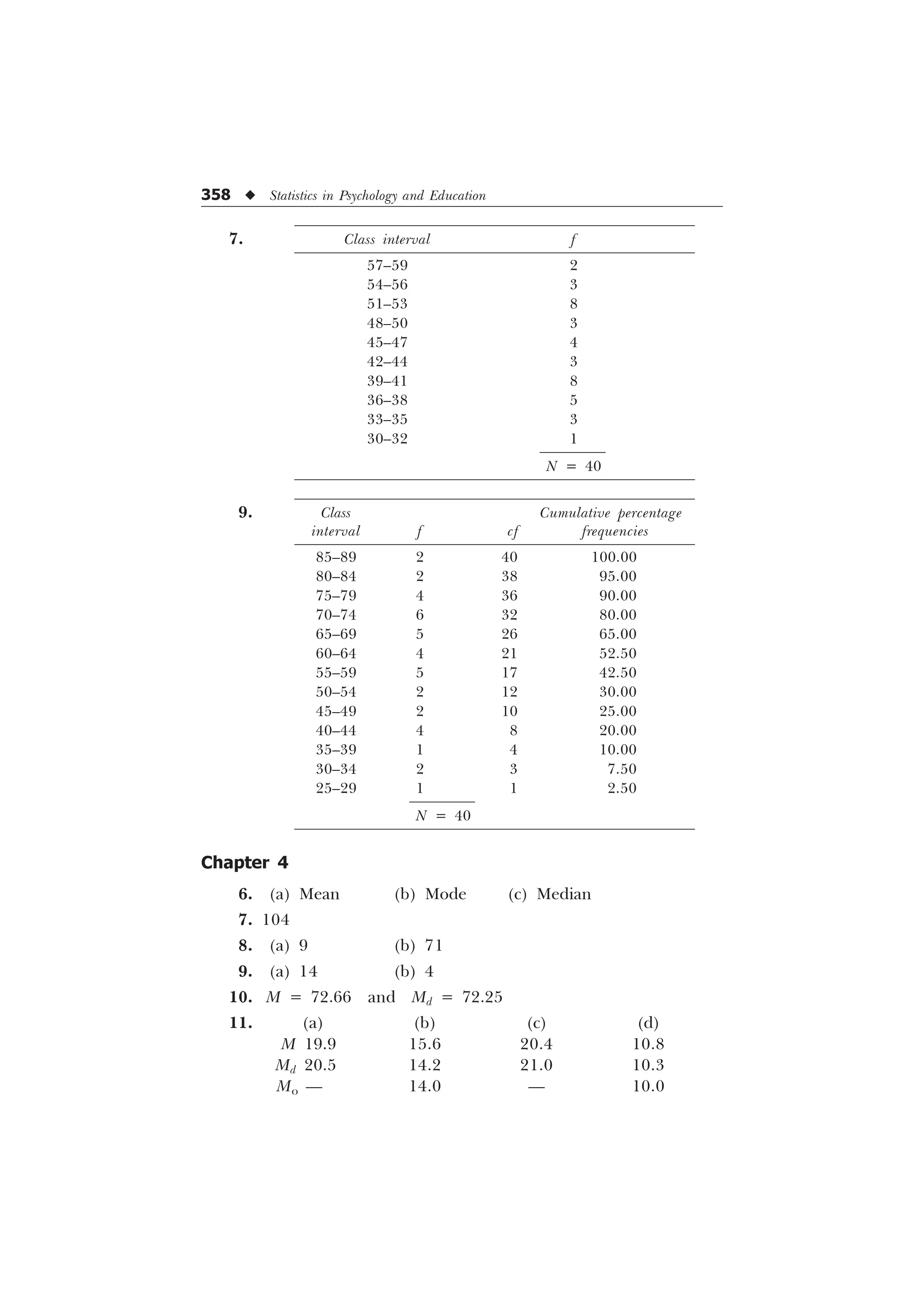

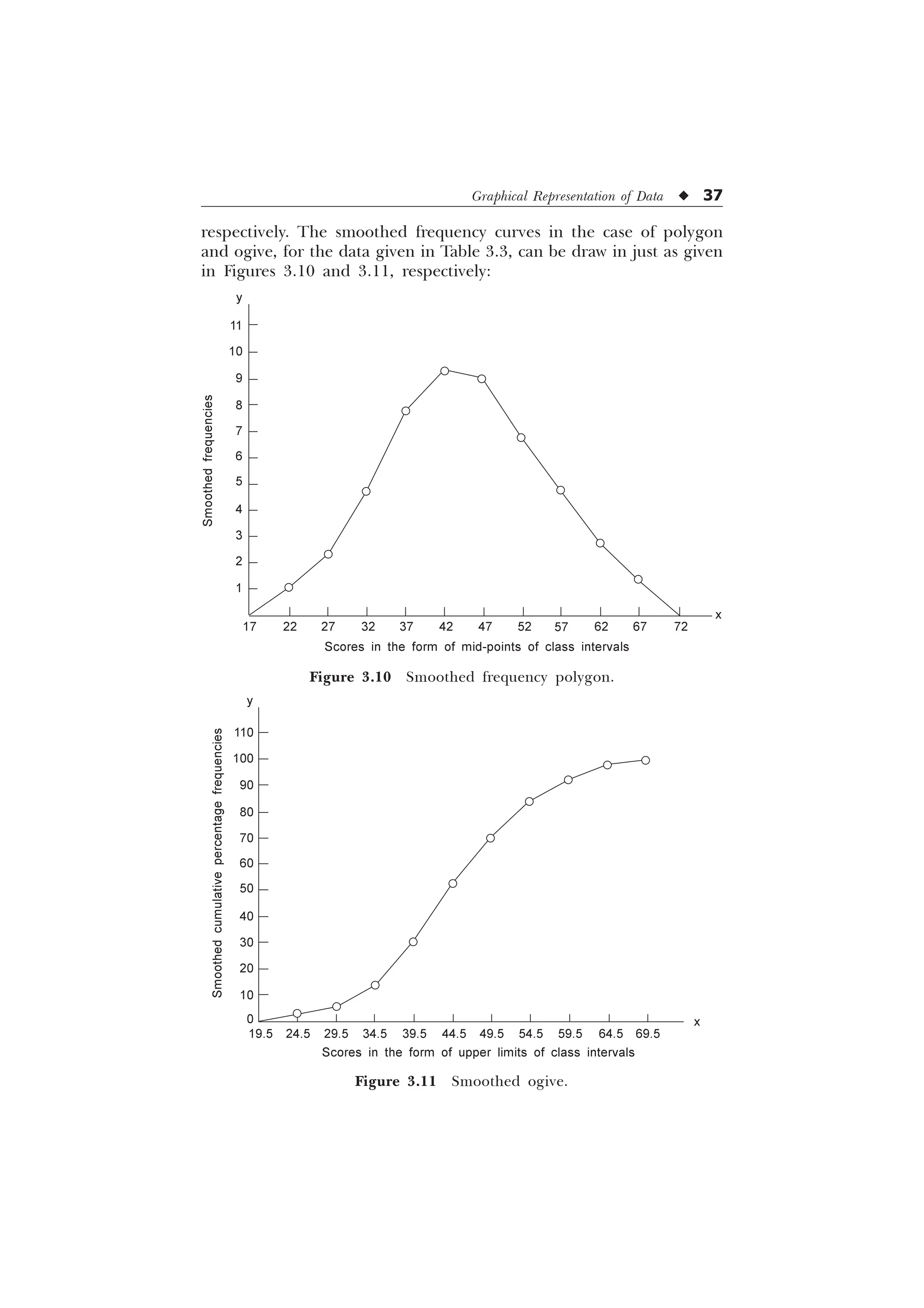

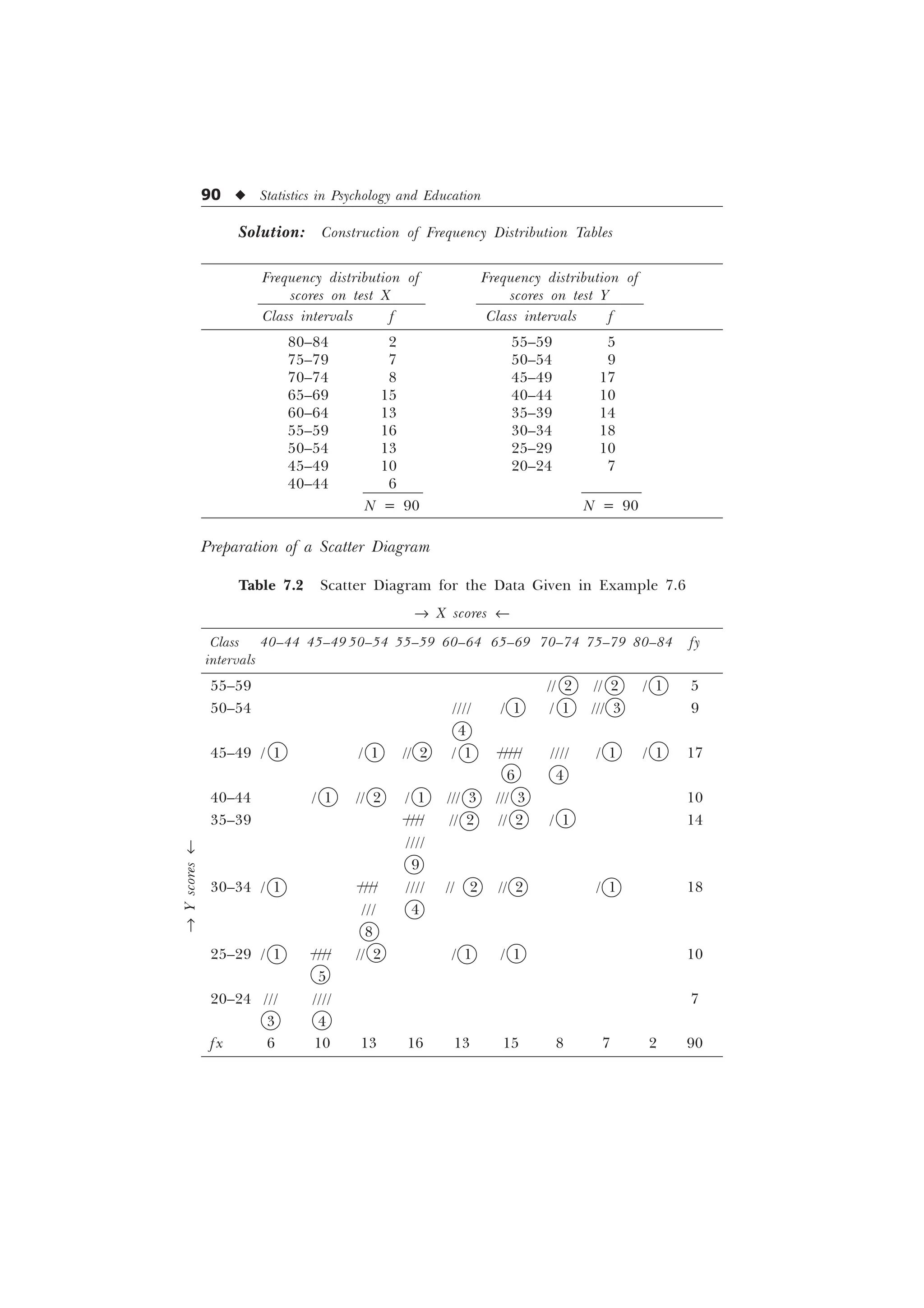

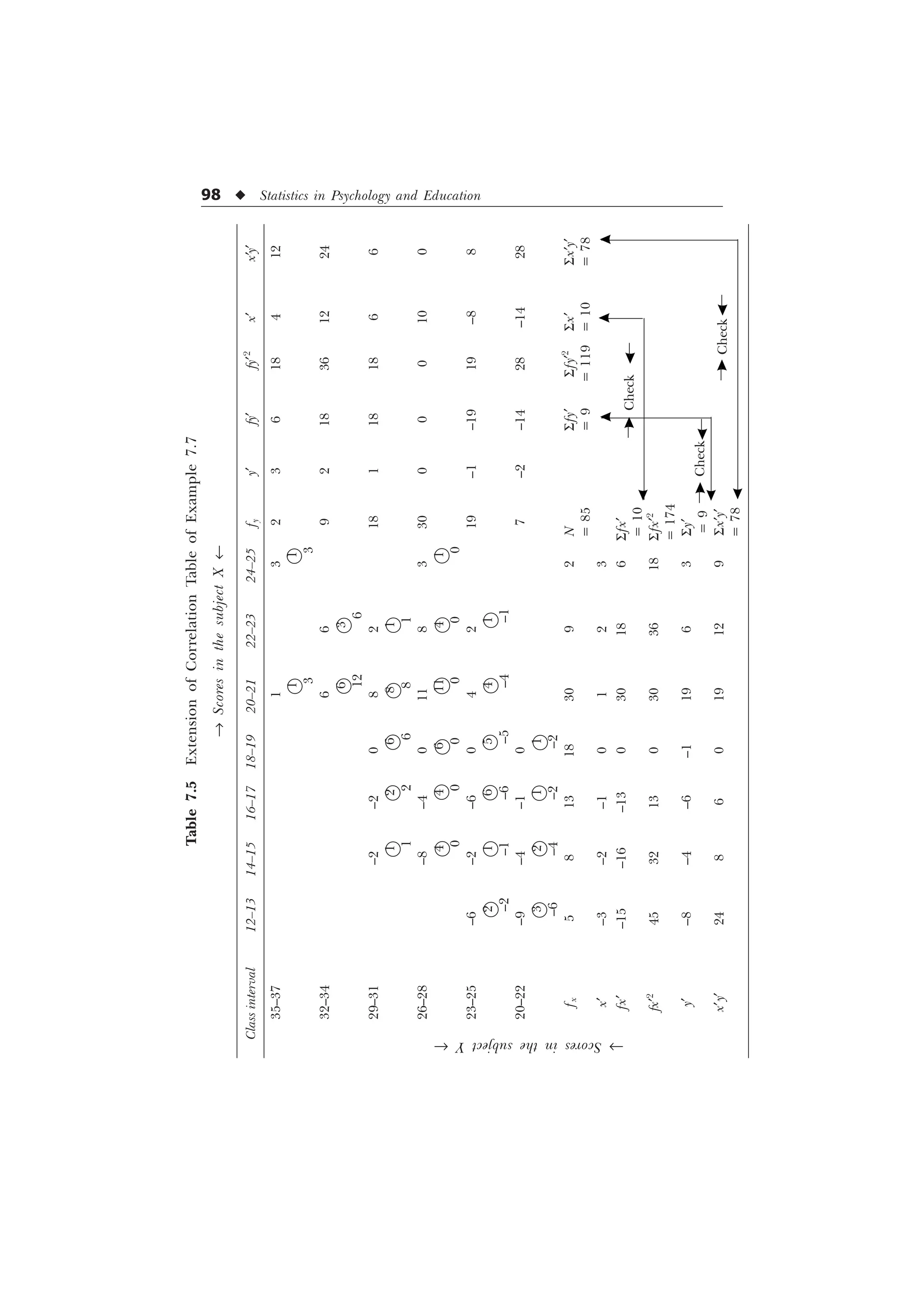

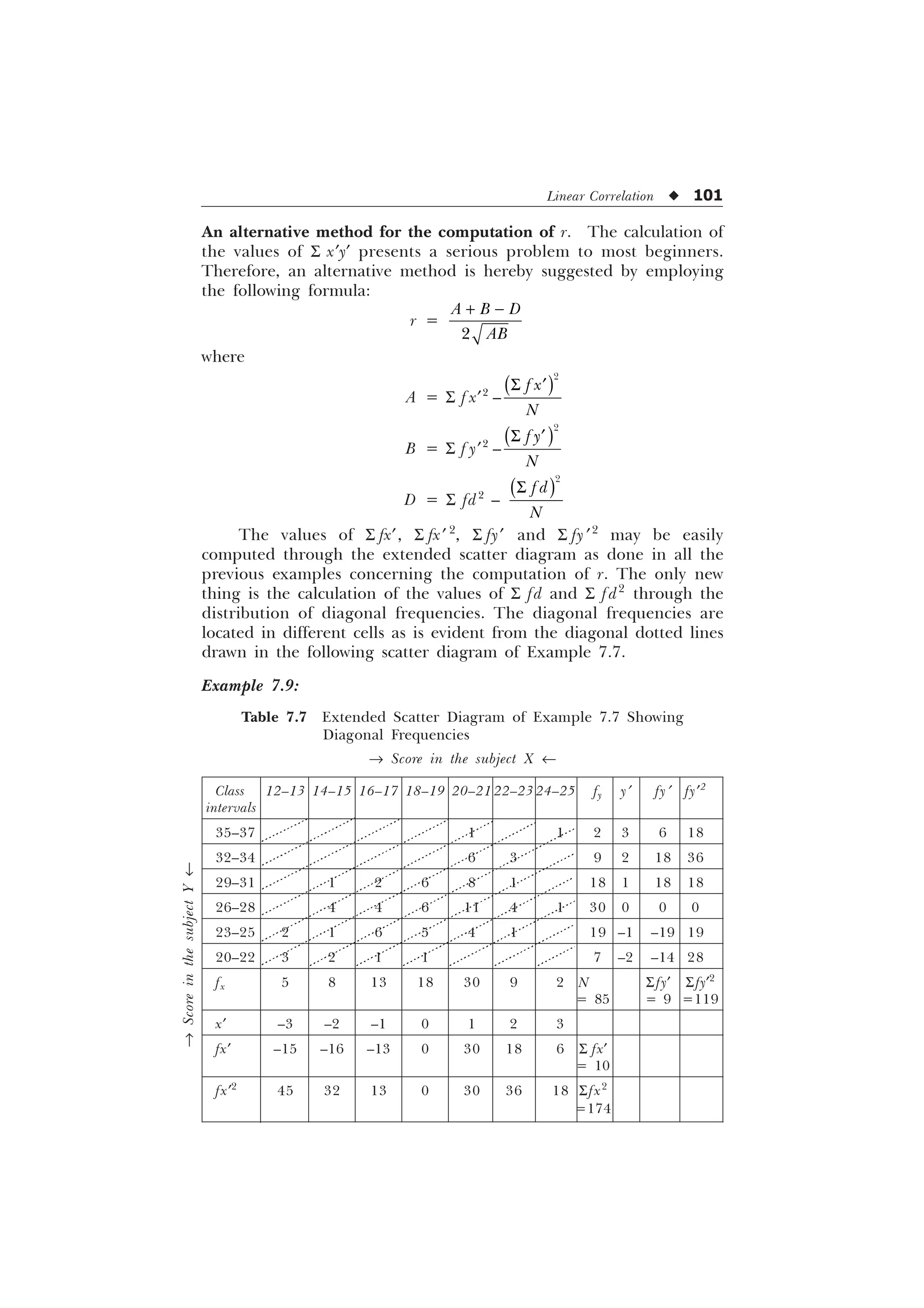

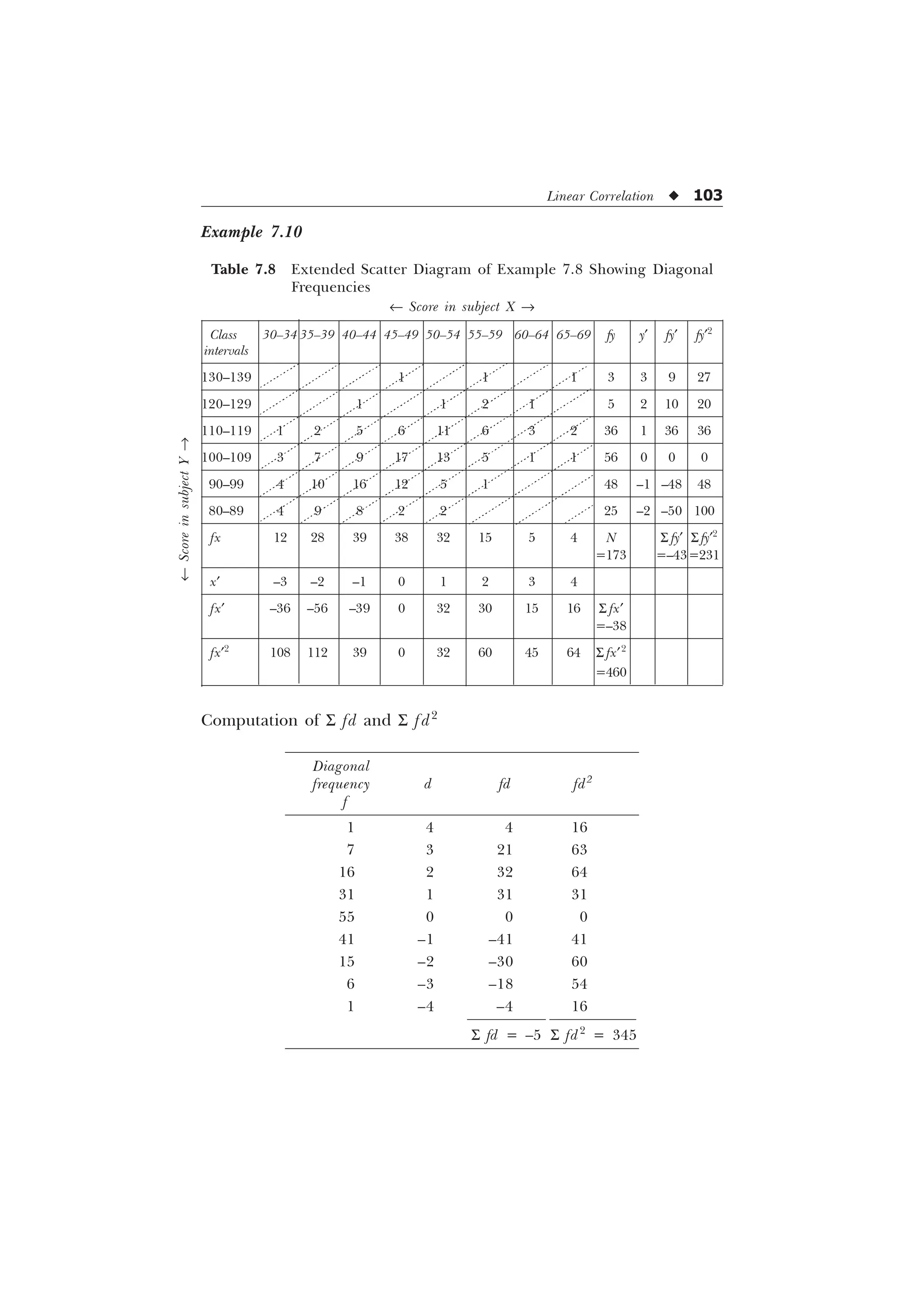

![Linear Correlation u 99

Example 7.8:

® Scores in the subject X ¬

Class 30–34 35–39 40–44 45–49 50–54 55–59 60–64 65–69 Total

intervals

130–139 1 1 1 3

120–129 1 1 2 1 5

110–119 1 2 5 6 11 6 3 2 36

100–109 3 7 9 17 13 5 1 1 56

90–99 4 10 16 12 5 1 48

80–89 4 9 8 2 2 25

Total 12 28 39 38 32 15 5 4 173

Solution: We will have extension of correlation table given in

Example 7.8 along with the computation of the needed values S x¢y¢,

S fx¢, S fy¢, S fx¢2

, S fy¢2

, as provided in Table 7.6.

Computation of r

r =

6 6 6

„ „ „ „

Ë Û Ë Û

6 6 6 6

„ „ „ „

Í Ý Í Ý

1 [ I [ I

1 I [ I [ 1 I I

=

– –

Ë Û Ë Û

– – – –

Í Ý Í Ý

=

=

–

=

=

= 0.518

= 0.52 (approx.)

[Ans. Pearson’s correlation coefficient = 0.52.]

®

Scores

in

the

subject

Y

¬](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/stats-s-241206101830-e3d4cc67/75/Stats-S-K-Mangal-statistics-textook-in-pdf-111-2048.jpg)

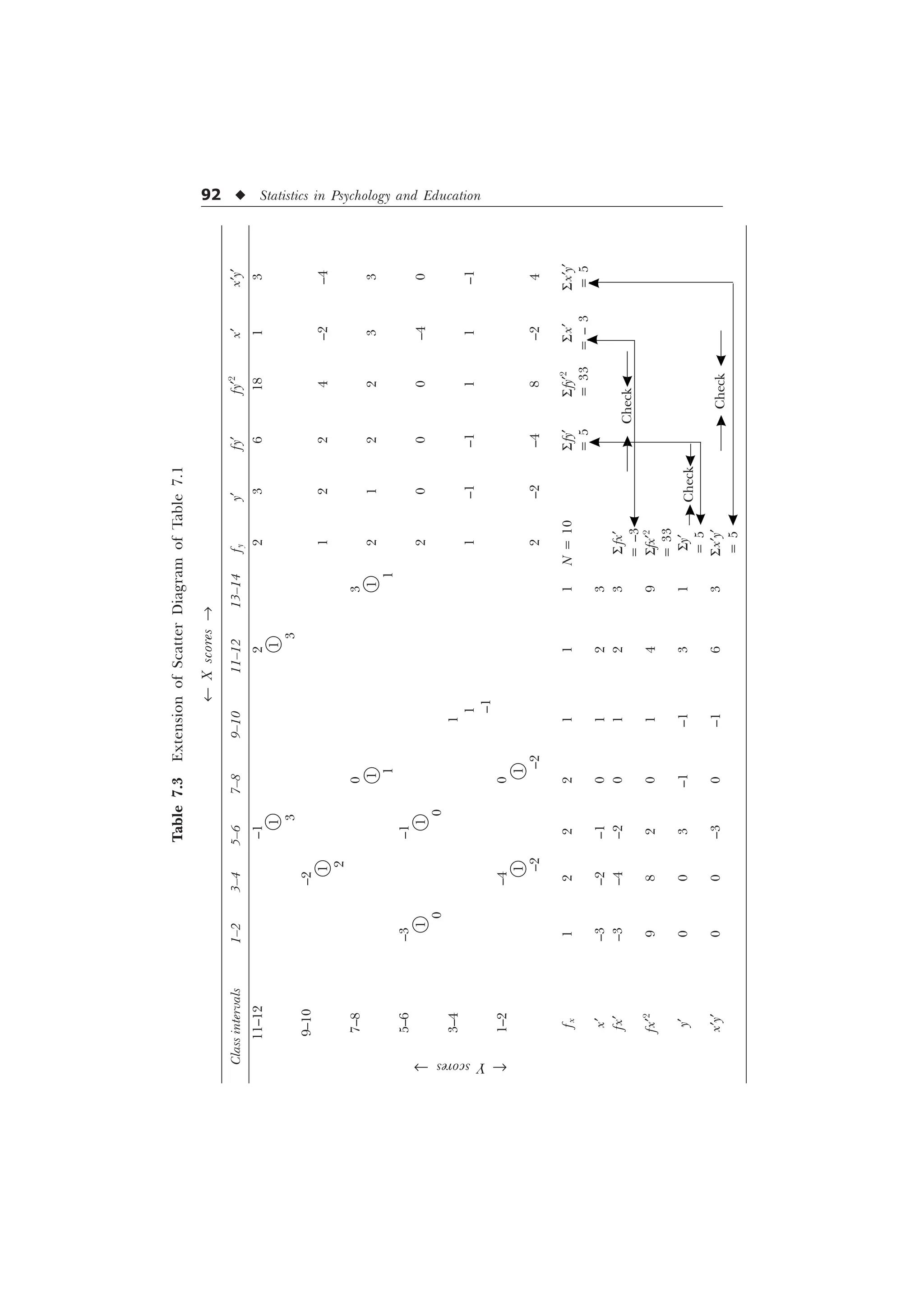

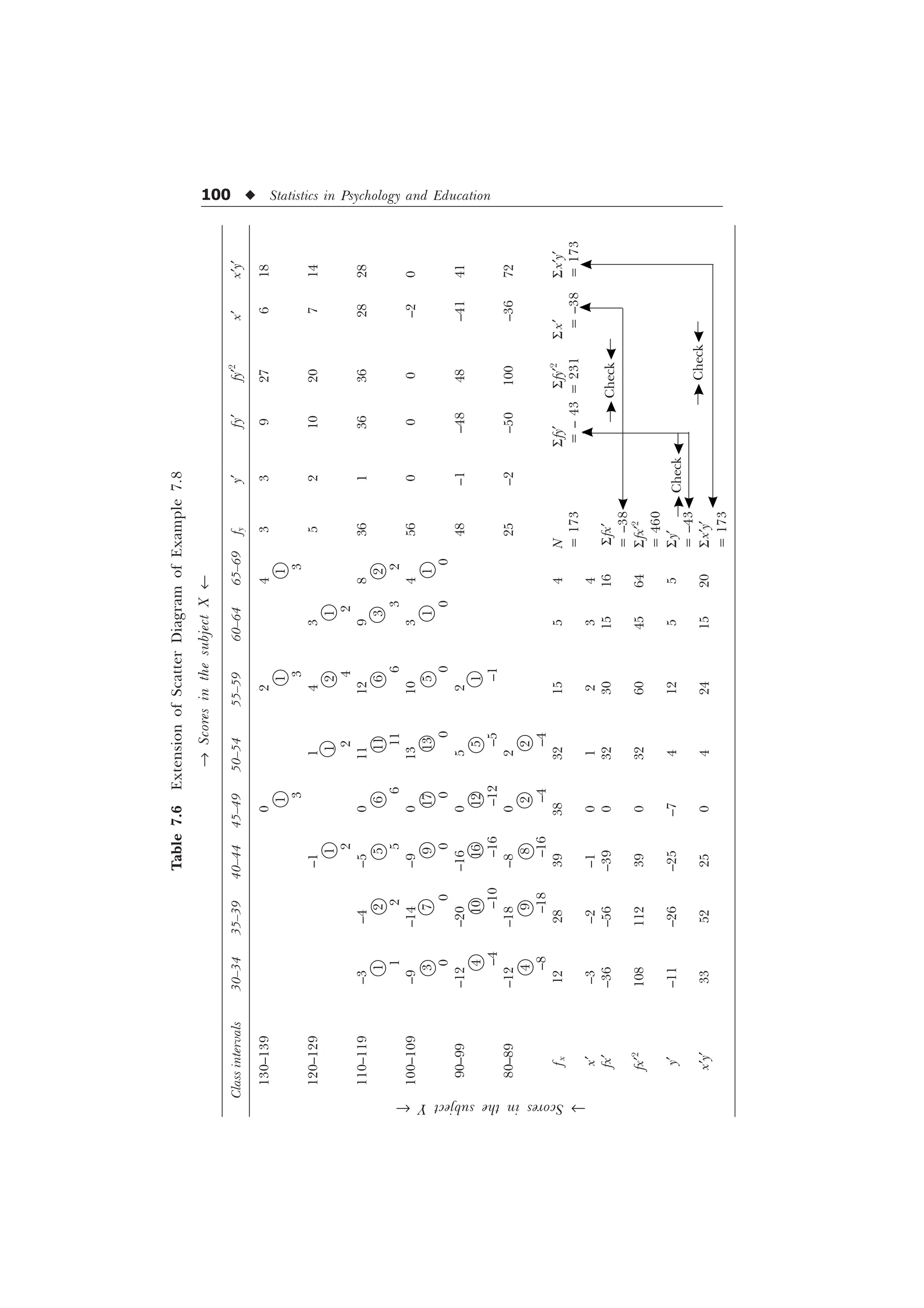

![102 u Statistics in Psychology and Education

The frequencies in the respective diagonal cells may be easily

located along the dotted lines of the above scatter diagram and the

process of the computation of the values of S fd and S fd2

may be

carried out as follows:

Diagonal

frequency d fd fd2

f

1 3 3 9

9 2 18 36

20 1 20 20

16 0 0 0

18 –1 –18 18

9 –2 –18 36

2 –3 –6 18

N = 85 S fd = –1 S fd2

= 137

The values of A, B and D can now be calculated as follows

A =

6 „

6

„

I [

I [

1

= 174 – 1.18 = 172.82

B =

6 „

6

„

I

I

1

= 119 – 0.95 = 118.05

D =

6

6

IG

IG

1

= 137 –

= 137 – 0.01

= 136.99

r =

$ % '

$%

=

–

=

–

=

= 0.539 = 0.54 (approx.)

[Ans. Product moment correlation coefficient = 0.54.]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/stats-s-241206101830-e3d4cc67/75/Stats-S-K-Mangal-statistics-textook-in-pdf-114-2048.jpg)

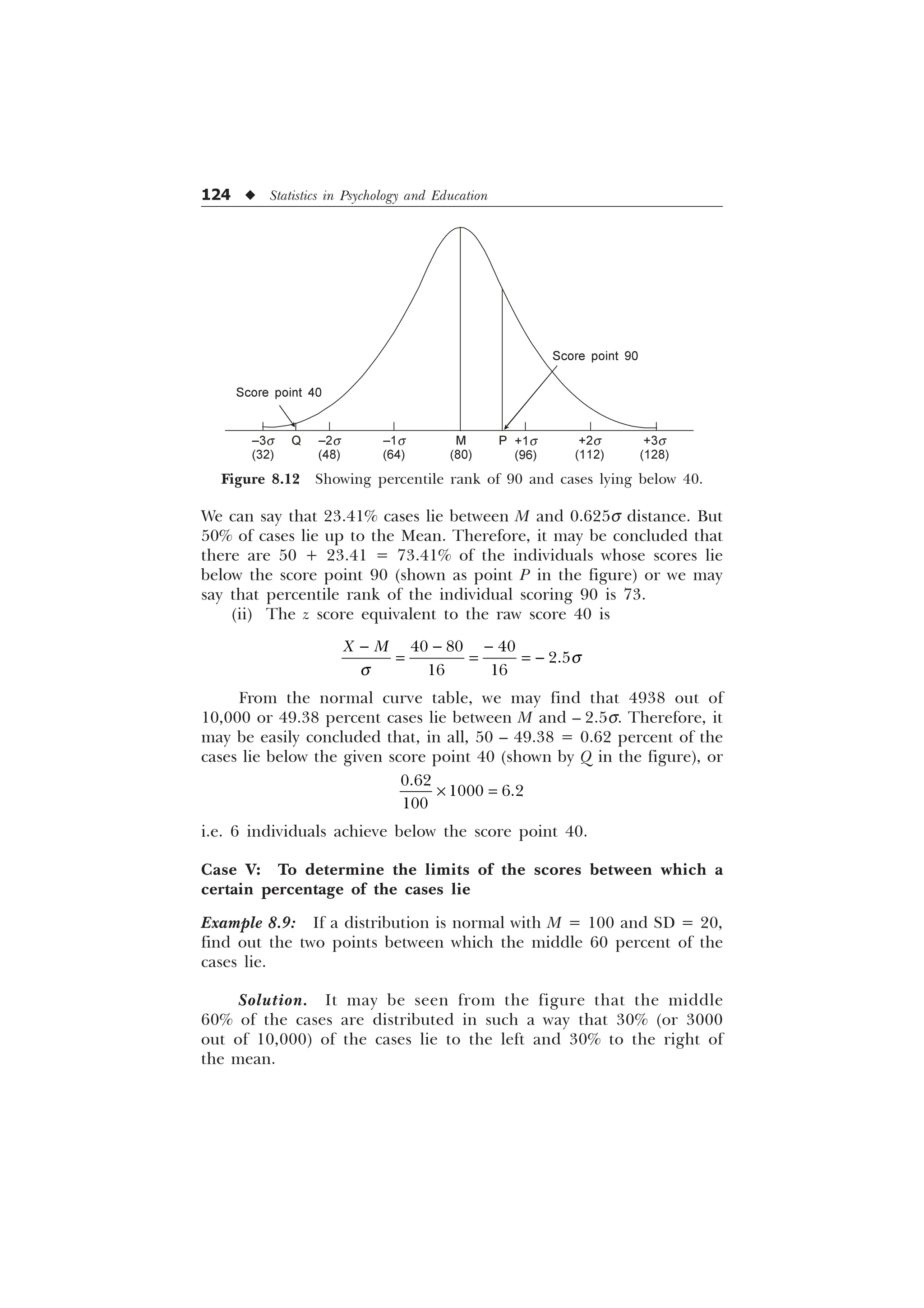

![118 u Statistics in Psychology and Education

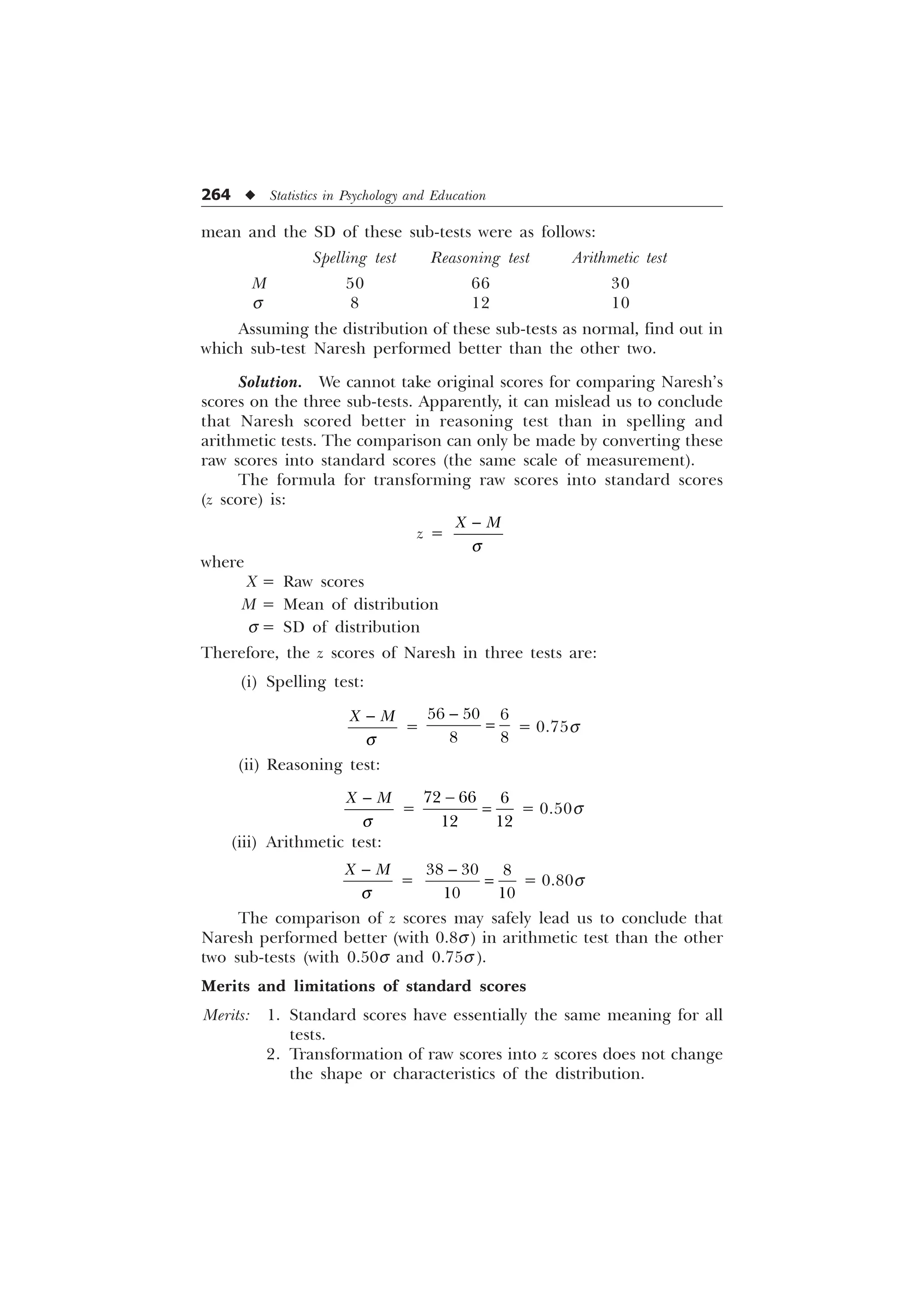

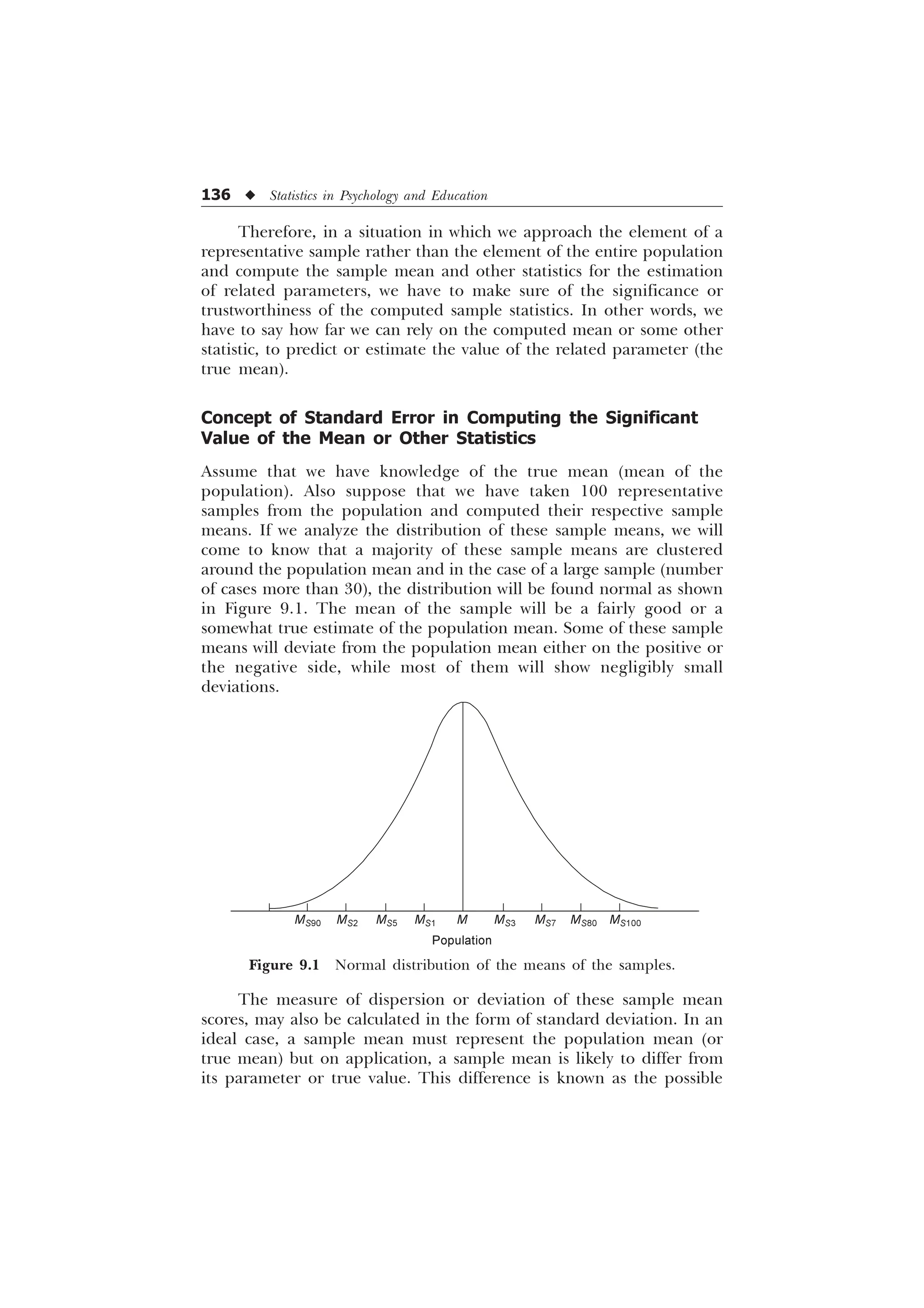

Understanding and Applying the Concept of Standard

Errors of Measurement

The normal curve as we have pointed out earlier, is also known as

the normal curve of error or simply the curve of error on the grounds

that it helps in understanding the concept of standard errors of

measurement. For example, if we compute mean for the distributions

of various samples taken from a single population, then, these means

will be found to be distributed normally around the mean of the entire

population. The sigma distance of a particular sample mean may help

us determine the standard error of measurement for the mean of that

sample.

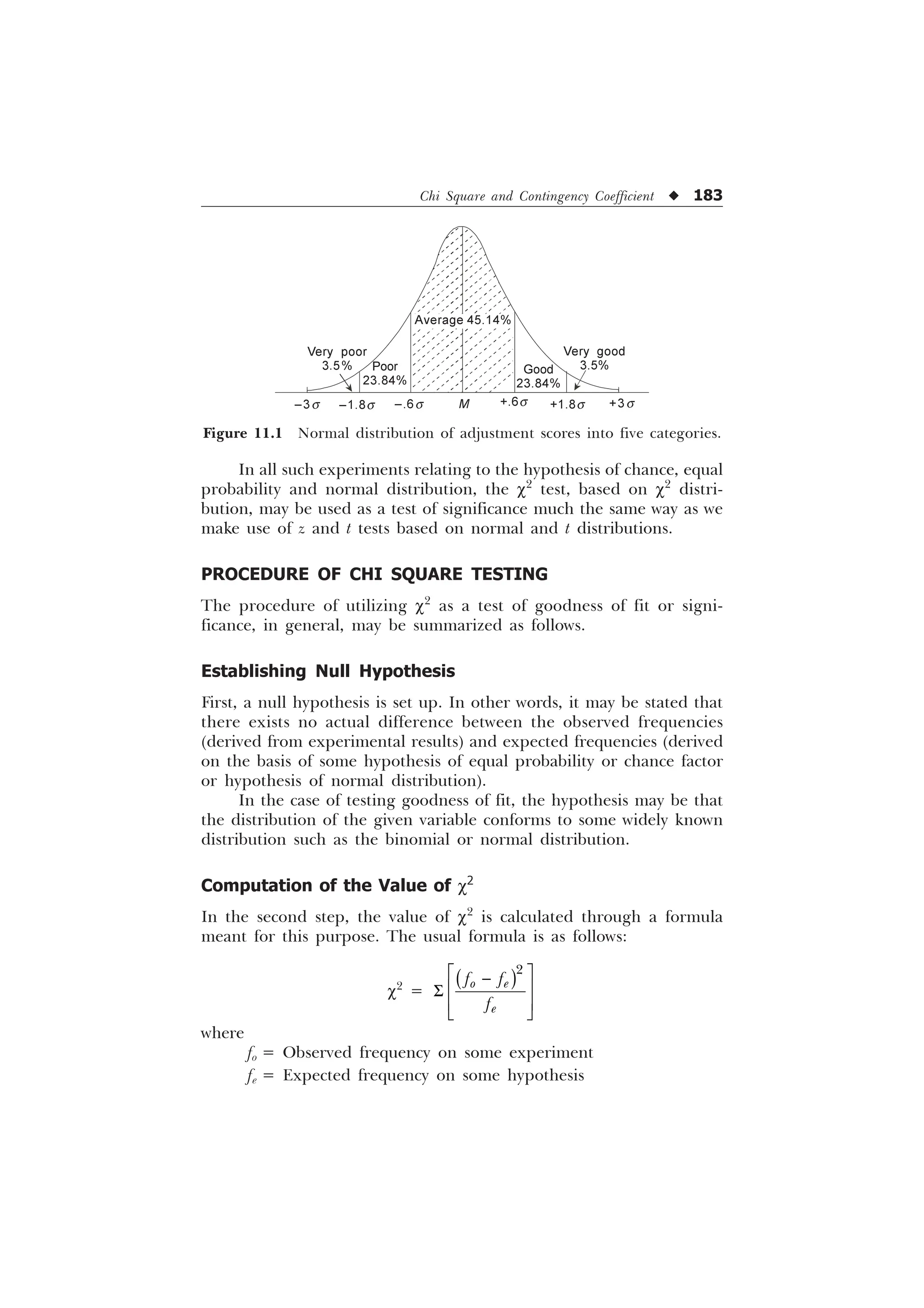

Ability Grouping

A group of individuals may be conveniently grouped into certain

categories as A, B, C, D, E (Very good, good, average, poor, very poor)

in terms of some trait (assumed to be normally distributed), with the

help of a normal curve.

Transforming and Combining Qualitative Data

Under the assumption of normality of the distributed variable, the sets

of qualitative data such as ratings, letter grades and categorical ranks

on a scale may be conveniently transformed and combined to provide

an average rating for each individual.

Converting Raw Scores into Comparable Standard

Normalized Scores

Sometimes, we have records of an individual’s performance on two or

more different kinds of assessment tests and we wish to compare his

score on one test with the score on the other. Unless the scales of these

two tests are the same, we cannot make a direct comparison. With the

help of a normal curve, we can convert the raw scores belonging to

different tests into standard normalized scores like sigma (or z scores)

and T-scores. For converting a given raw score into a z score, we

subtract the mean of the scores of the distribution from the respective

raw scores and divide it by the standard deviation of the distribution

LH

; 0

]

T

È Ø

É Ù

Ê Ú . In this way, a standard z score clearly indicates how

many standard deviation units a raw score is above or below the mean

and thus provides a standard scale for the purpose of valuable](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/stats-s-241206101830-e3d4cc67/75/Stats-S-K-Mangal-statistics-textook-in-pdf-130-2048.jpg)

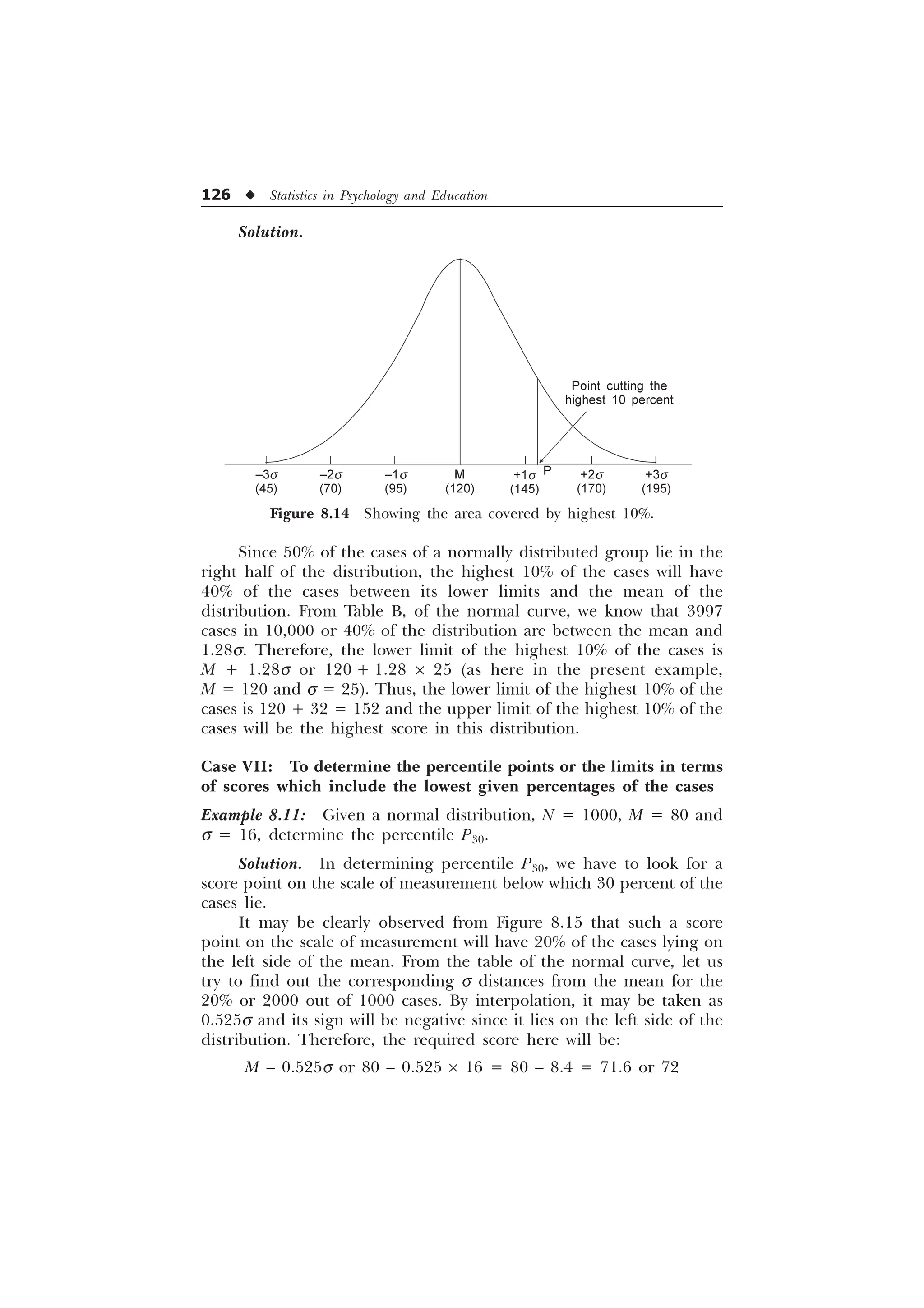

![120 u Statistics in Psychology and Education

]

Example 8.2: Given M = 48, s = 8, for a distribution, convert a z

score (s score) of the value 0.625 into a raw score.

Solution

; 0

]

T

Putting known values in the given formula, we get

0.625 =

;

or

X = 0.625 ´ 8 + 48 = 5.0 + 48 = 53

Making Use of the Table of Normal Curve

Table B of the normal curve (given in the Appendix) provides the

fractional parts of the total area (taken as 10,000) under the curve in

relation to the respective sigma distances from the mean. This table

may therefore be used to find the fractional part of the total area when

z scores or sigma scores are given and also to find the sigma or z scores,

when the fractional parts of the total area are given. Let us illustrate

it with the help of examples.

Example 8.3: From the table of the normal distribution, read the

areas from mean to 2.73s.

Solution. We have to look for the figure of the total area given

in the table corresponding to 2.73s score. For this we have to first

locate 2.7 sigma distance in the first column headed by

; 0

]

T

(s scores) and then move horizontally in the row against 2.7 until we

reach the place below the sigma distance .03 (lying in column 4). The

figure 4968 gives the fractional parts of the total area (taken as 10000)

corresponding to the 2.73s distance (lying on the right side) from the

mean of the curve. Consequently, 4968/10000 or 49.68 percent of the

cases may be said to lie between the mean and 2.73s.

Example 8.4: From the table of the normal distribution read the value

of sigma score from the mean for the corresponding fractional area

3729.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/stats-s-241206101830-e3d4cc67/75/Stats-S-K-Mangal-statistics-textook-in-pdf-132-2048.jpg)

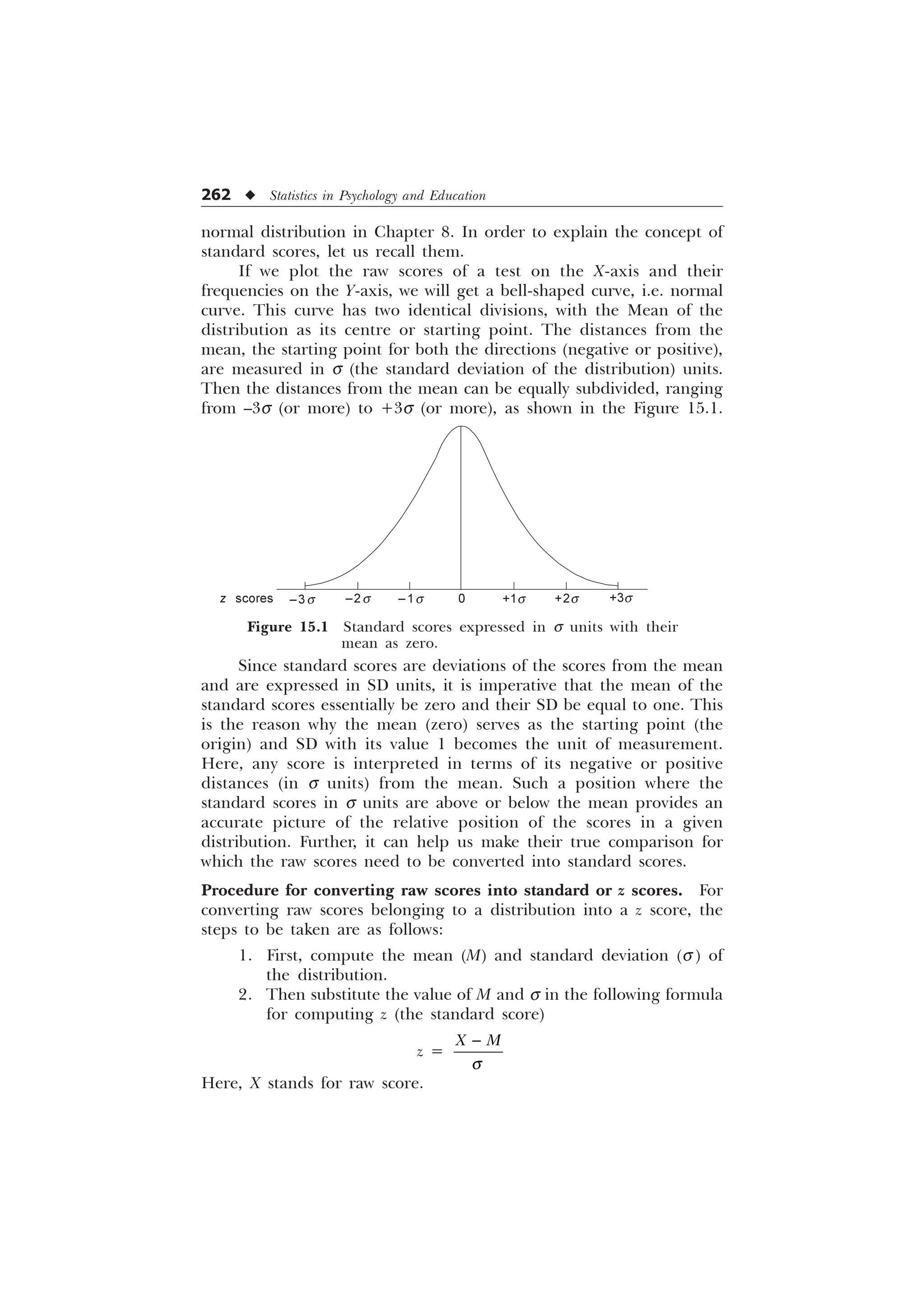

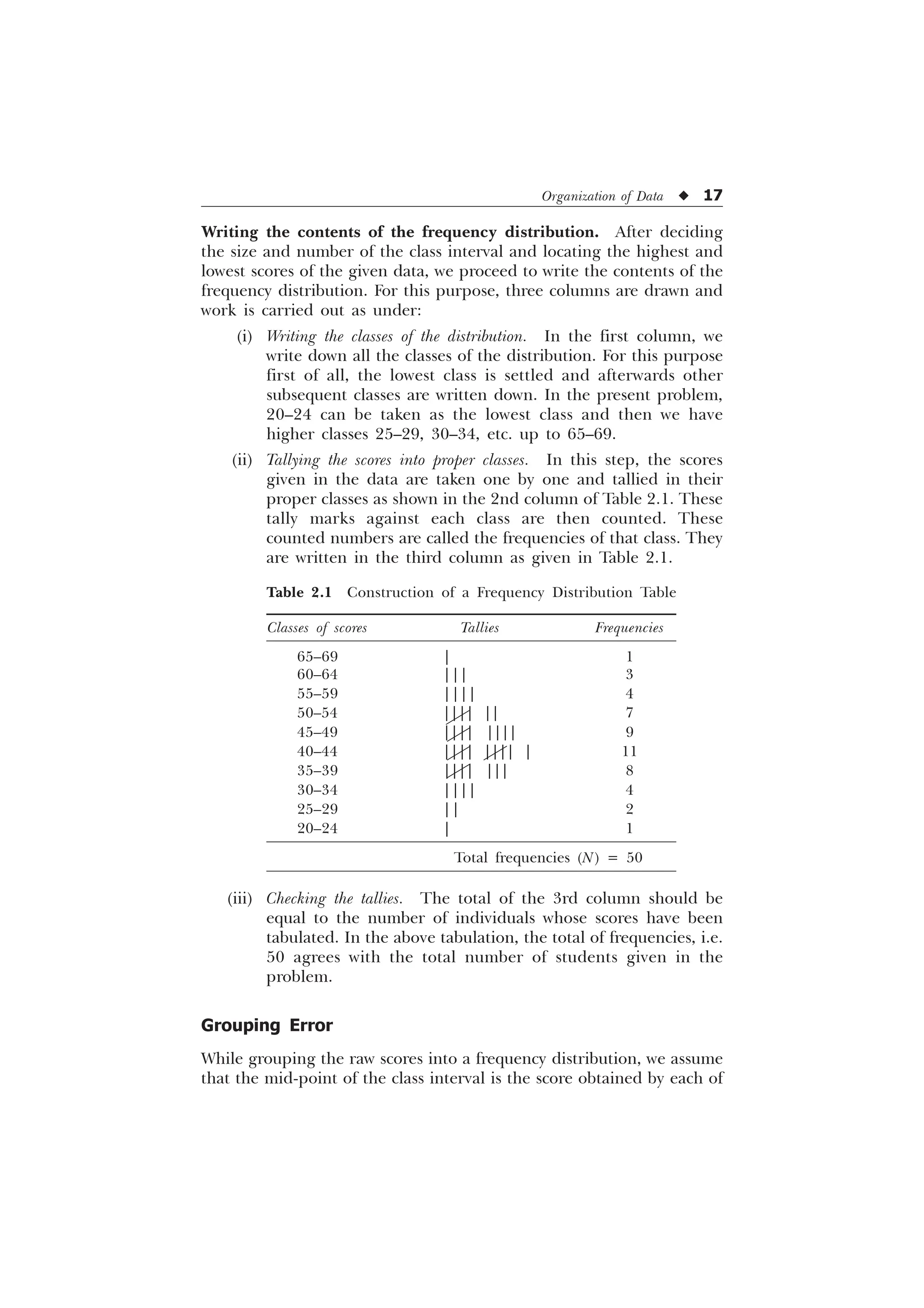

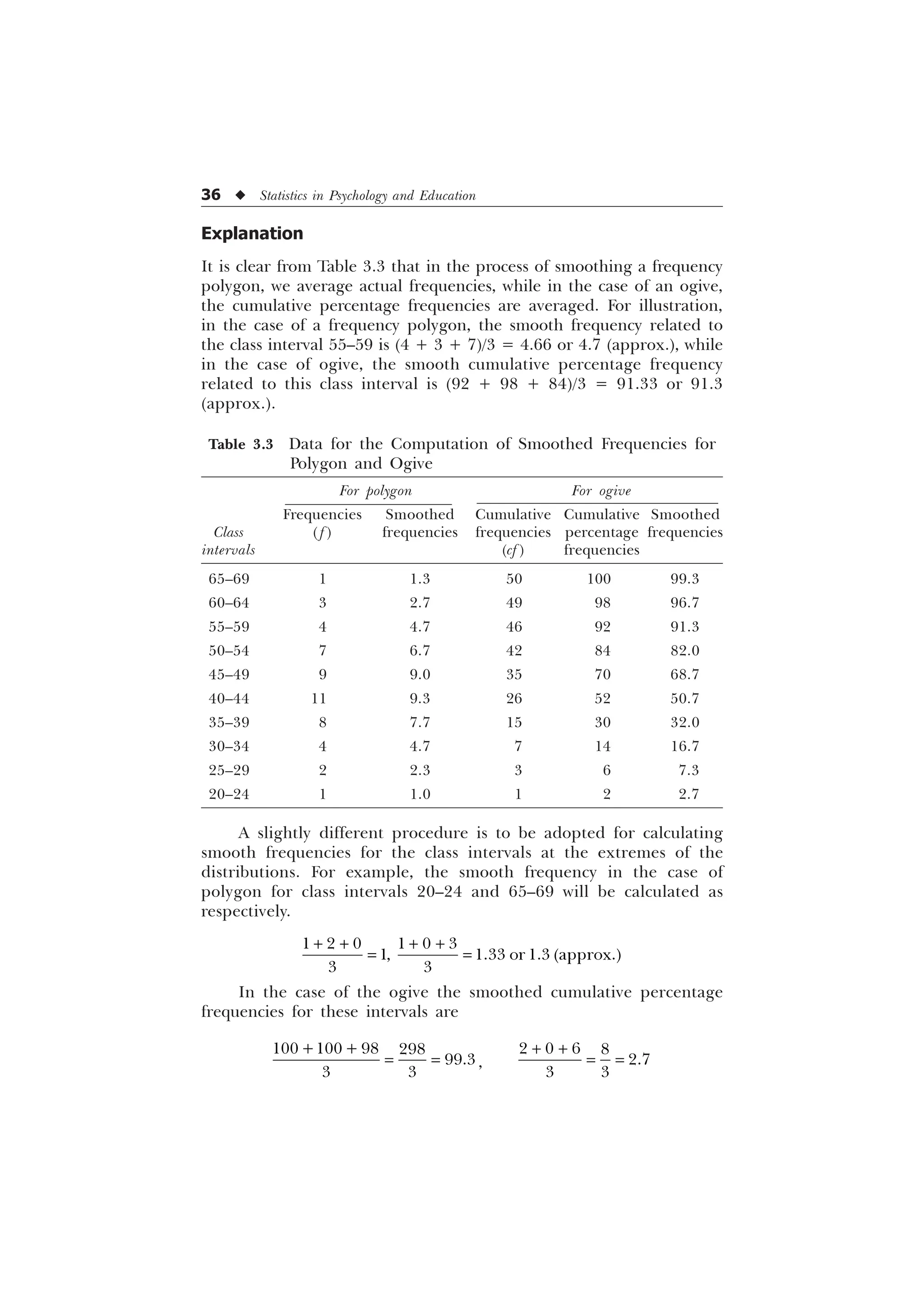

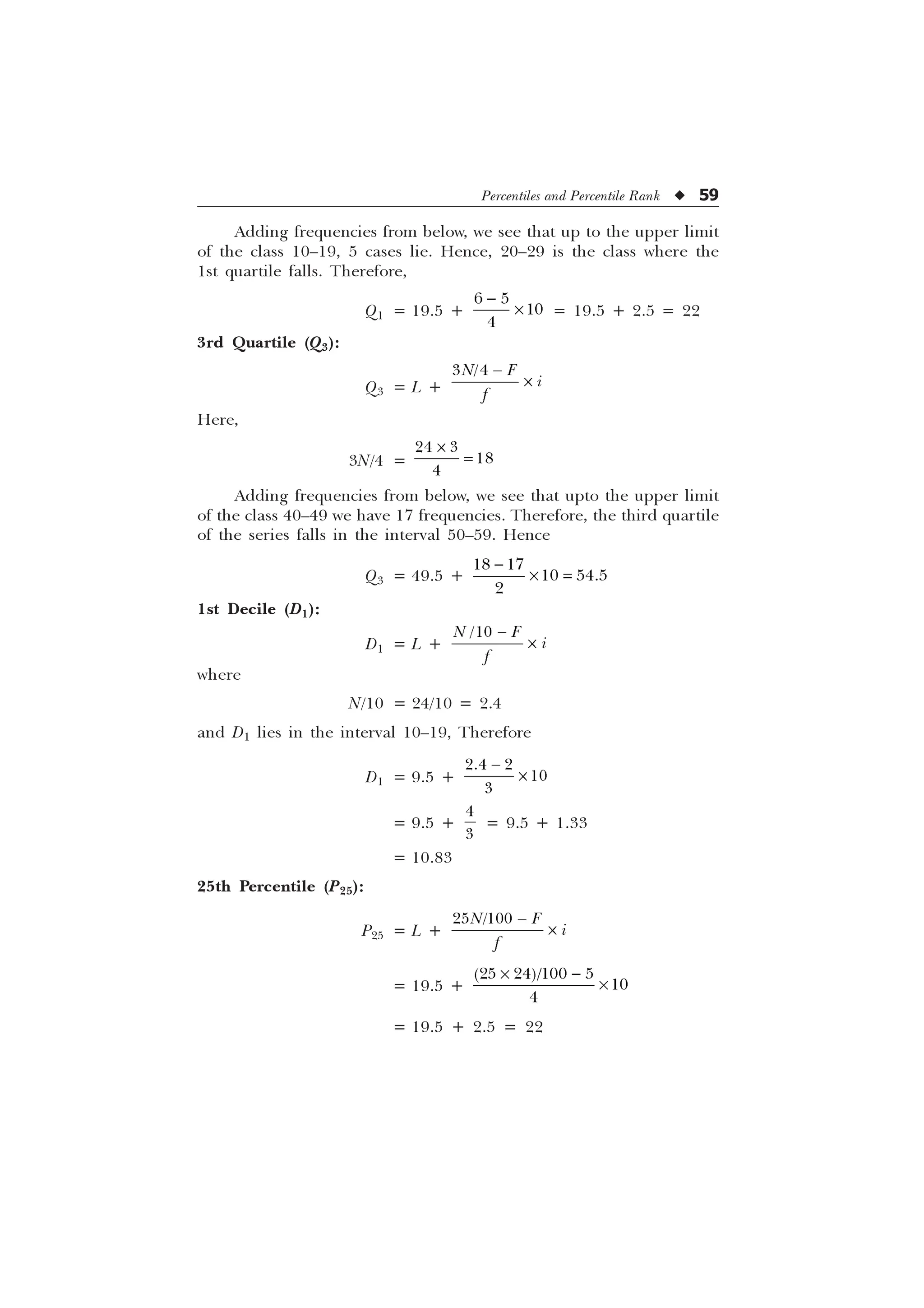

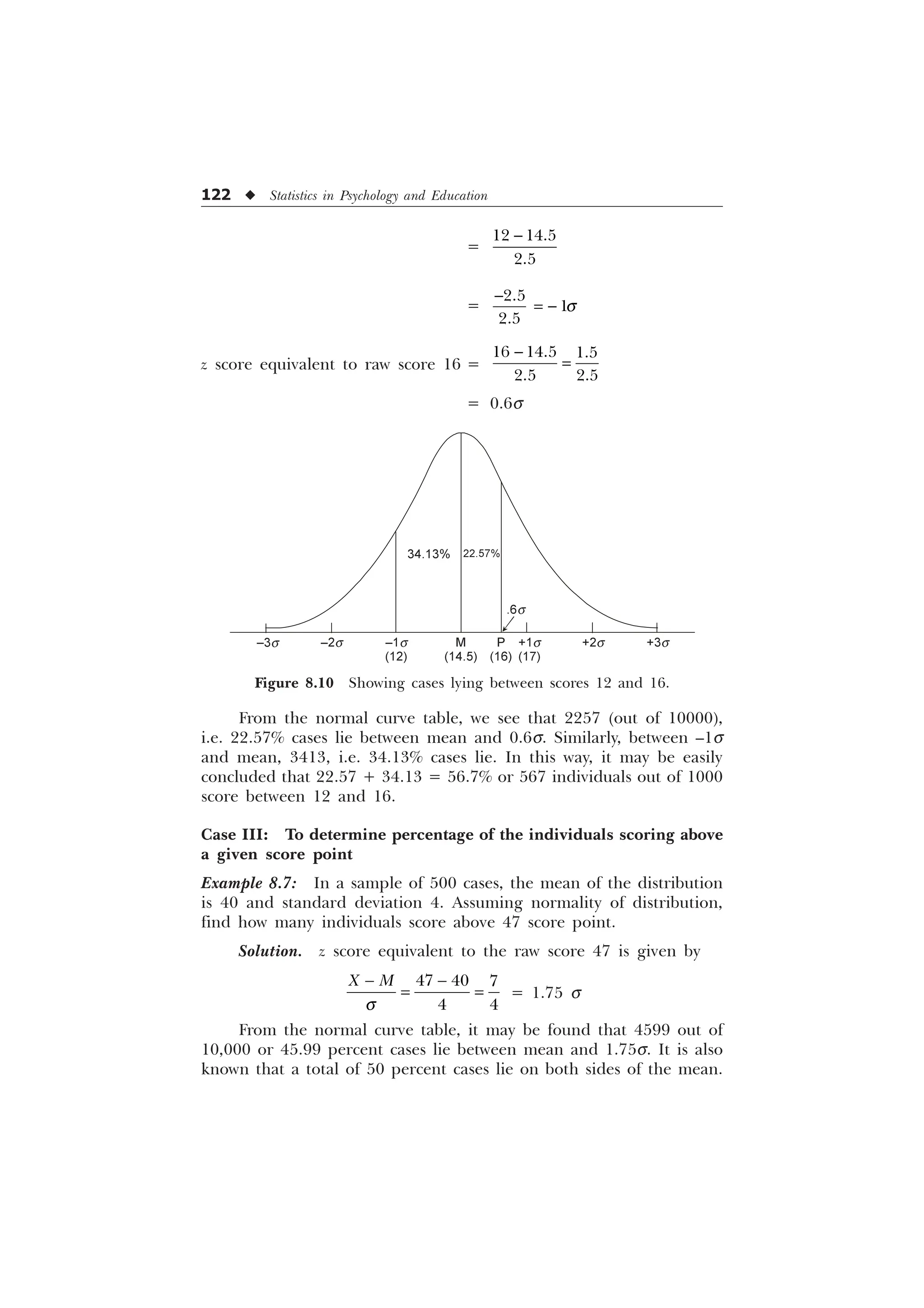

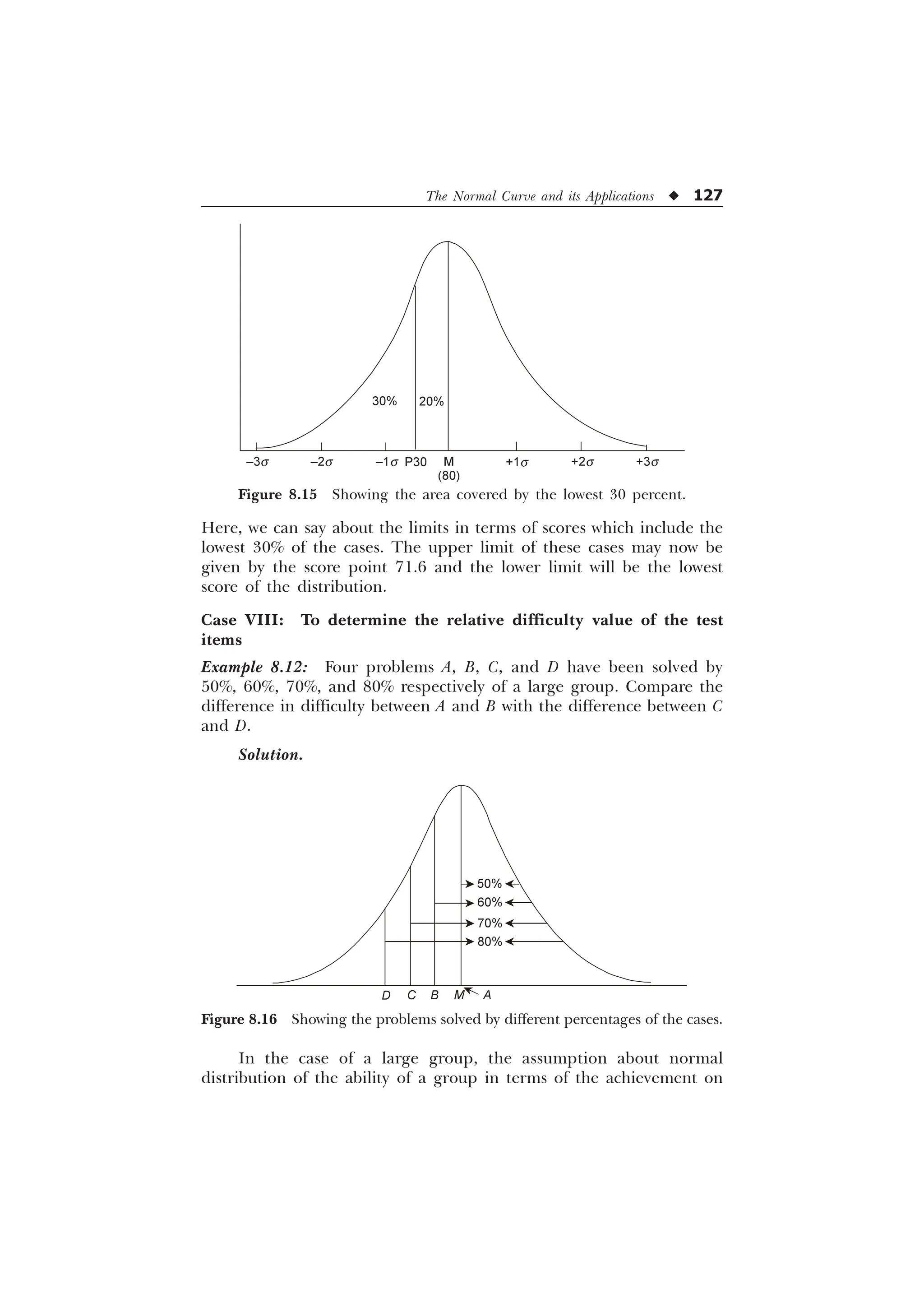

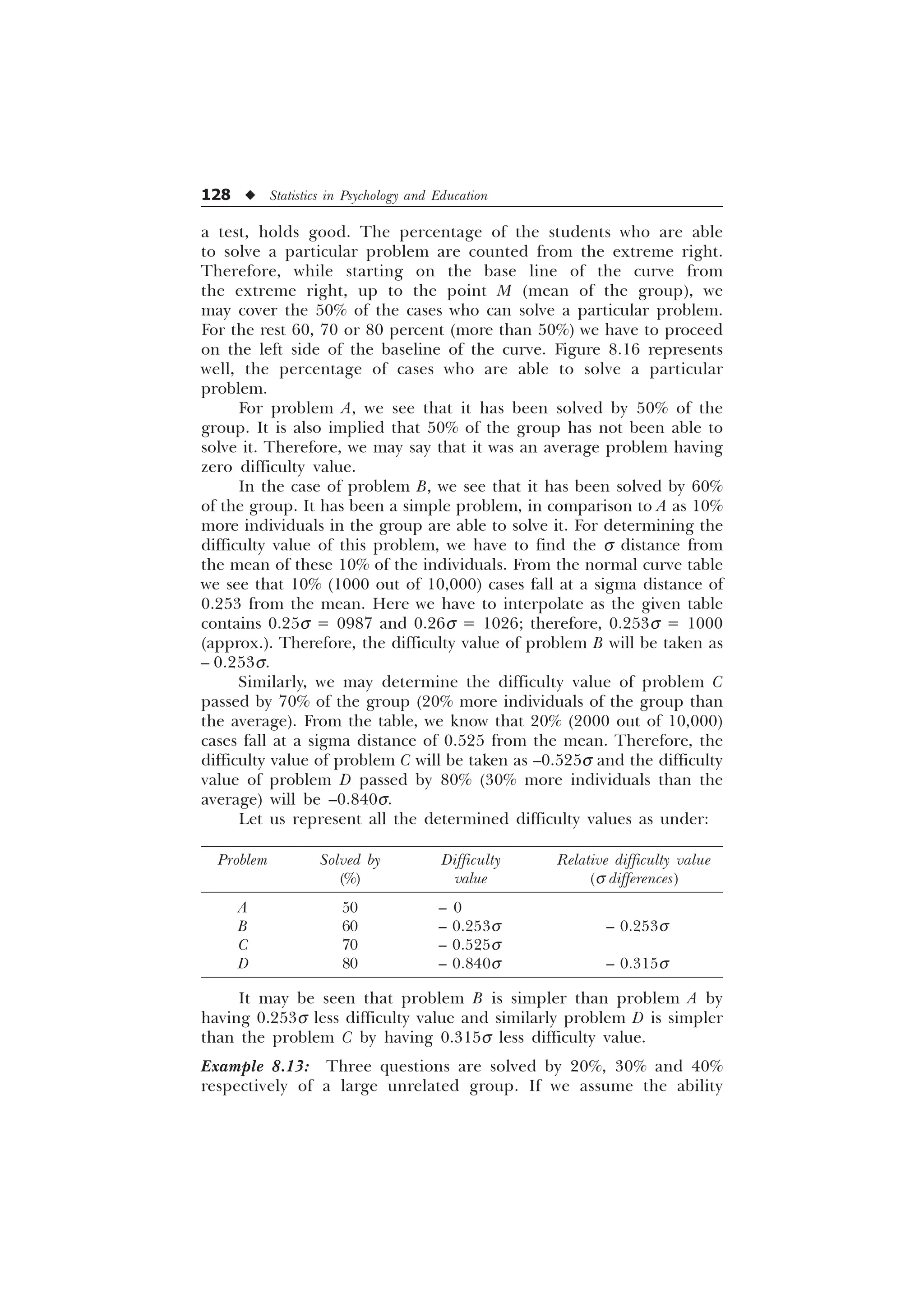

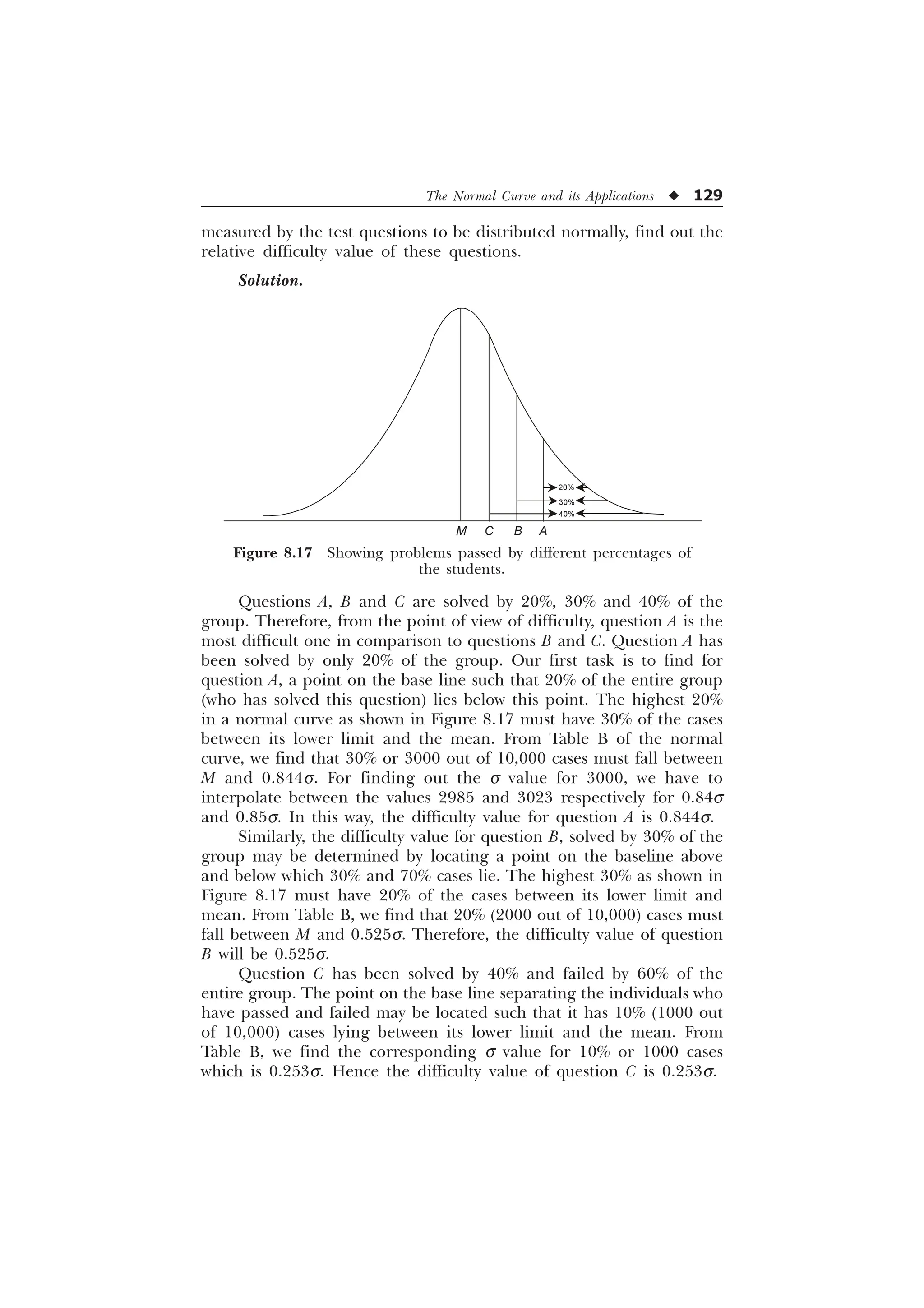

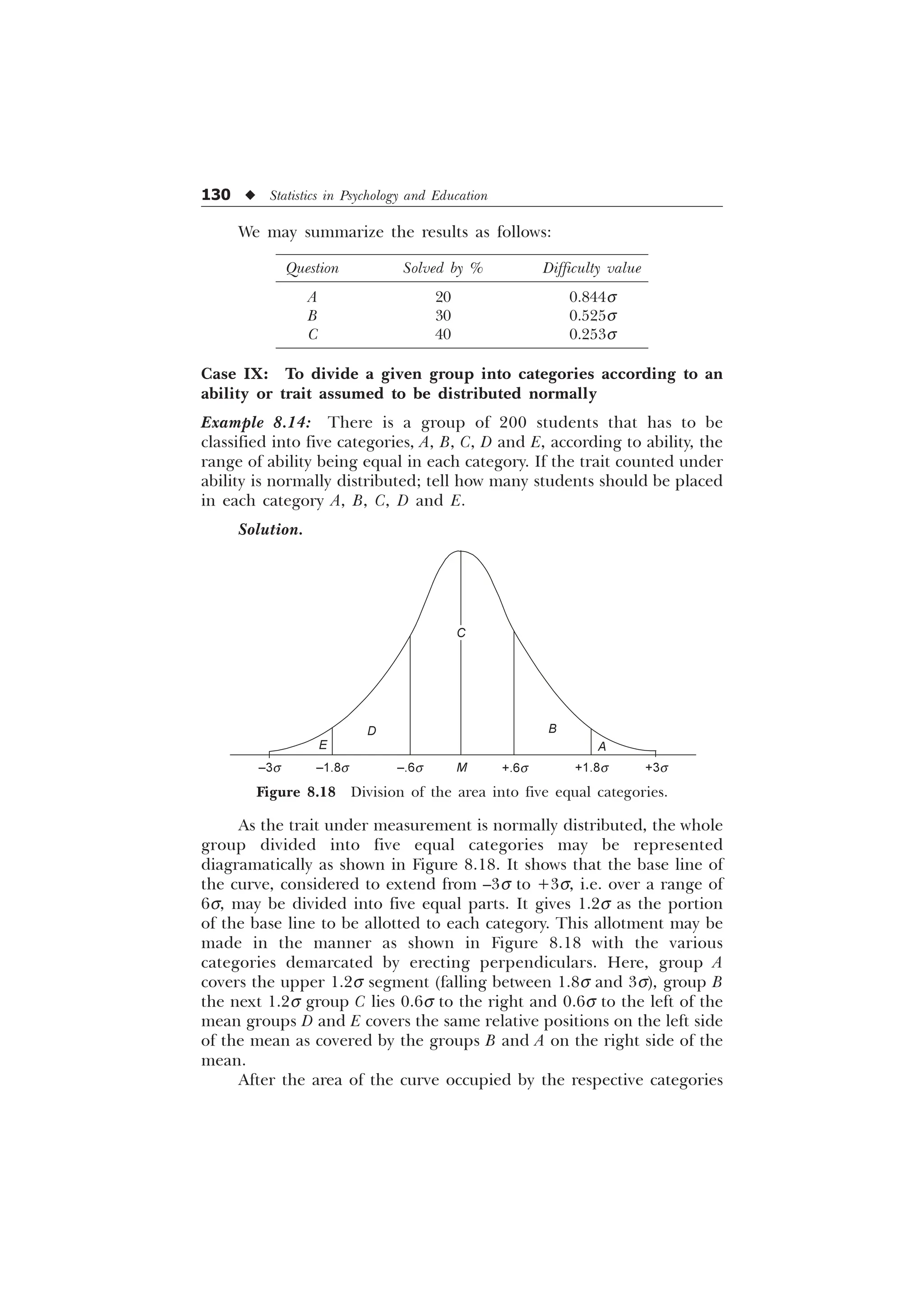

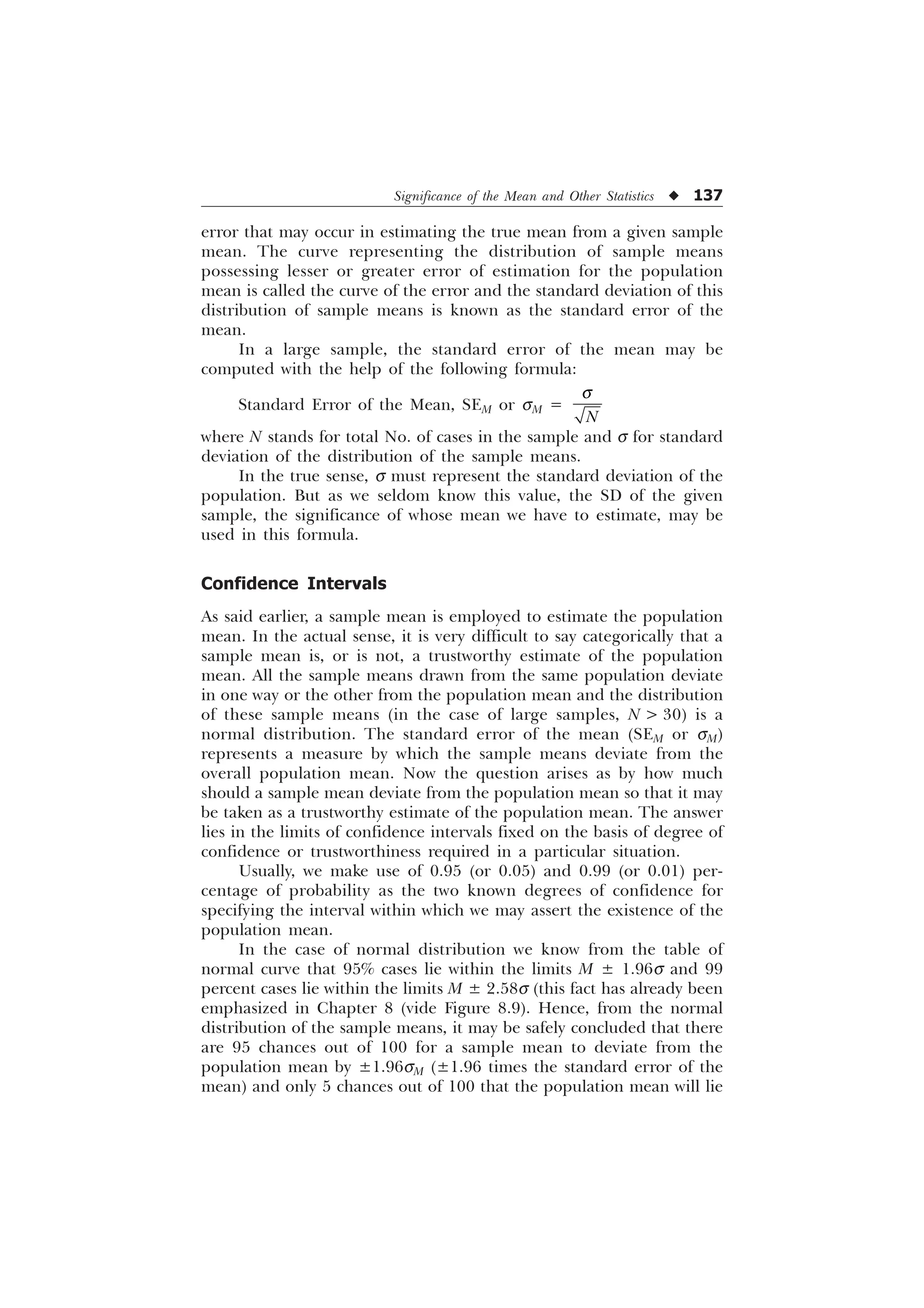

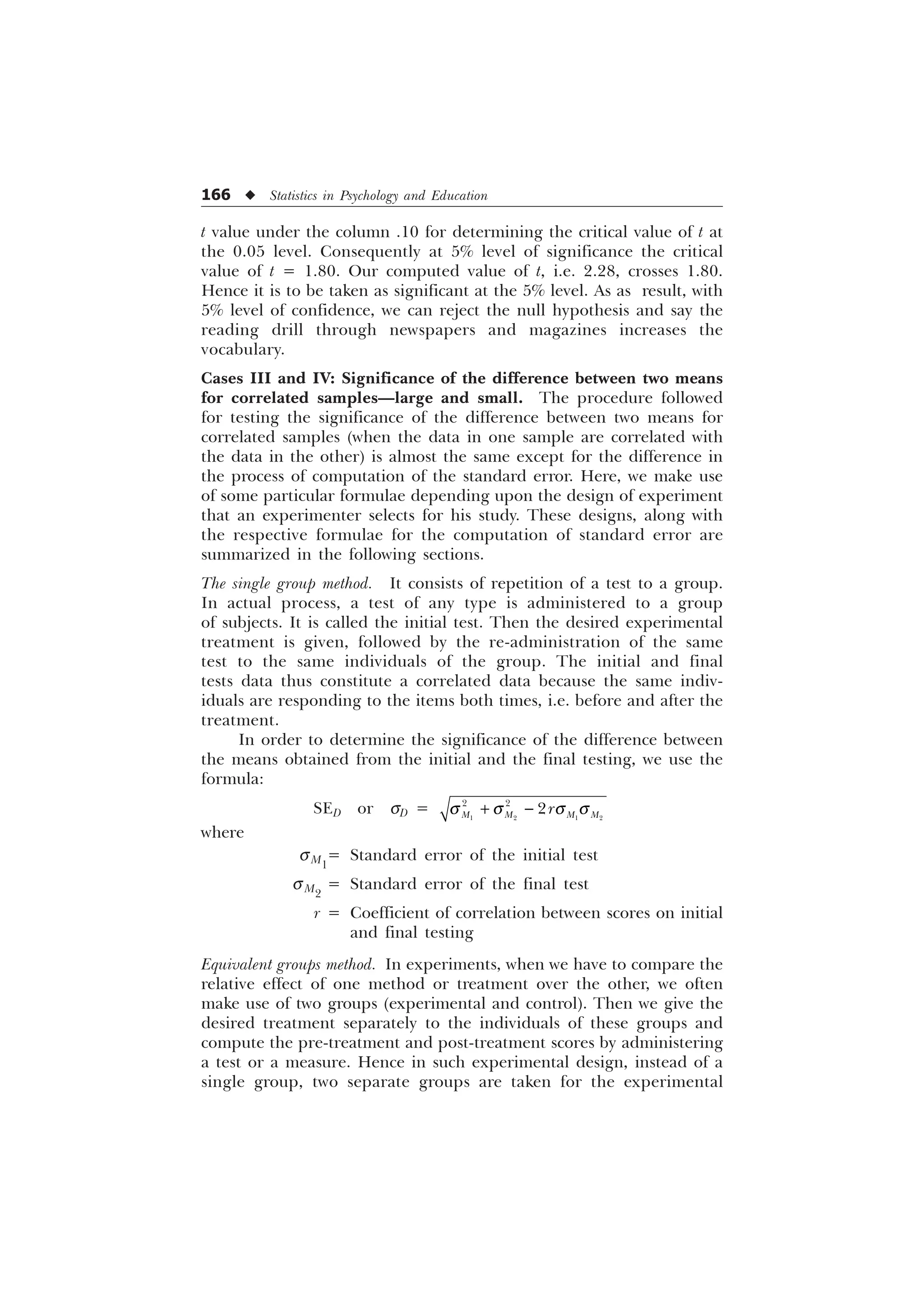

![The Normal Curve and its Applications u 125

From the normal curve (Table B in the Appendix), we have to

find out the corresponding s distance for the 3000 fractional parts of

the total area under the normal curve. There is a figure of 2995 for

area in the table (very close to 3000) for which we may read sigma

value as 0.84s. It means that 30% of the cases lie on the right side of

the curve between M and 0.84s and similarly 30% of the cases lie on

the left side of the figure between M and –0.84s. The middle 60% of

the cases, therefore, fall between the mean and standard score +0.84s.

We have to convert the standard z scores to raw scores with the help

of the formulae

z =

T T

; 0

; 0

]

or

0.48 =

DQG

;

;

or

X1 = 16.8 + 100 and X2 = 100 – 16.8

or

X1 = 116.8 and X2 = 83.2

After rounding the figures, we have the scores 117 and 83 that

include the middle 60 percent of the cases.

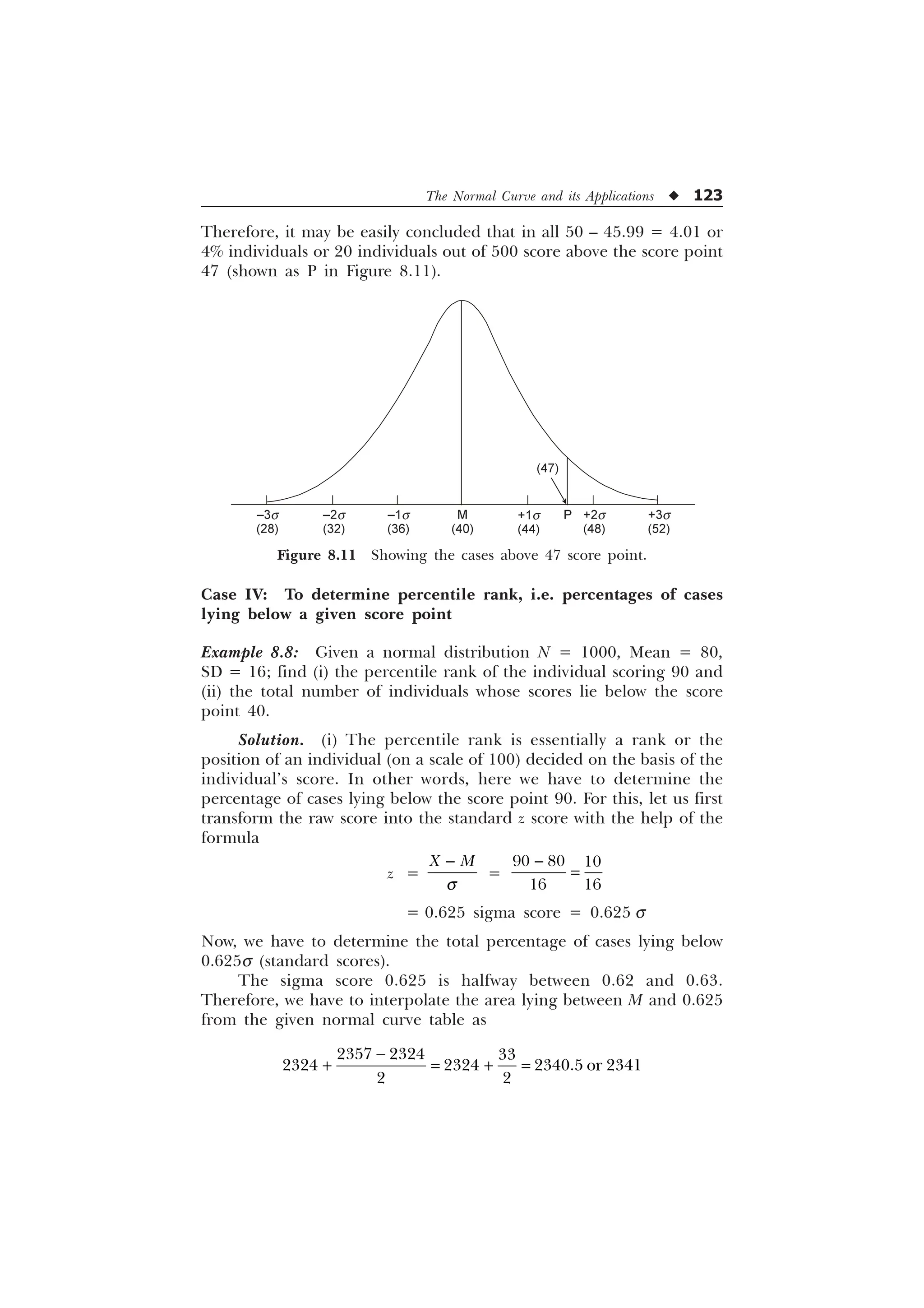

Case VI: To find out the limits in terms of scores which include

the highest given percentages of the cases

Example 8.10: Given a normal distribution with a mean of 120 and

SD of 25, what limits will include the highest 10% of the distribuution

(see Figure 8.14).

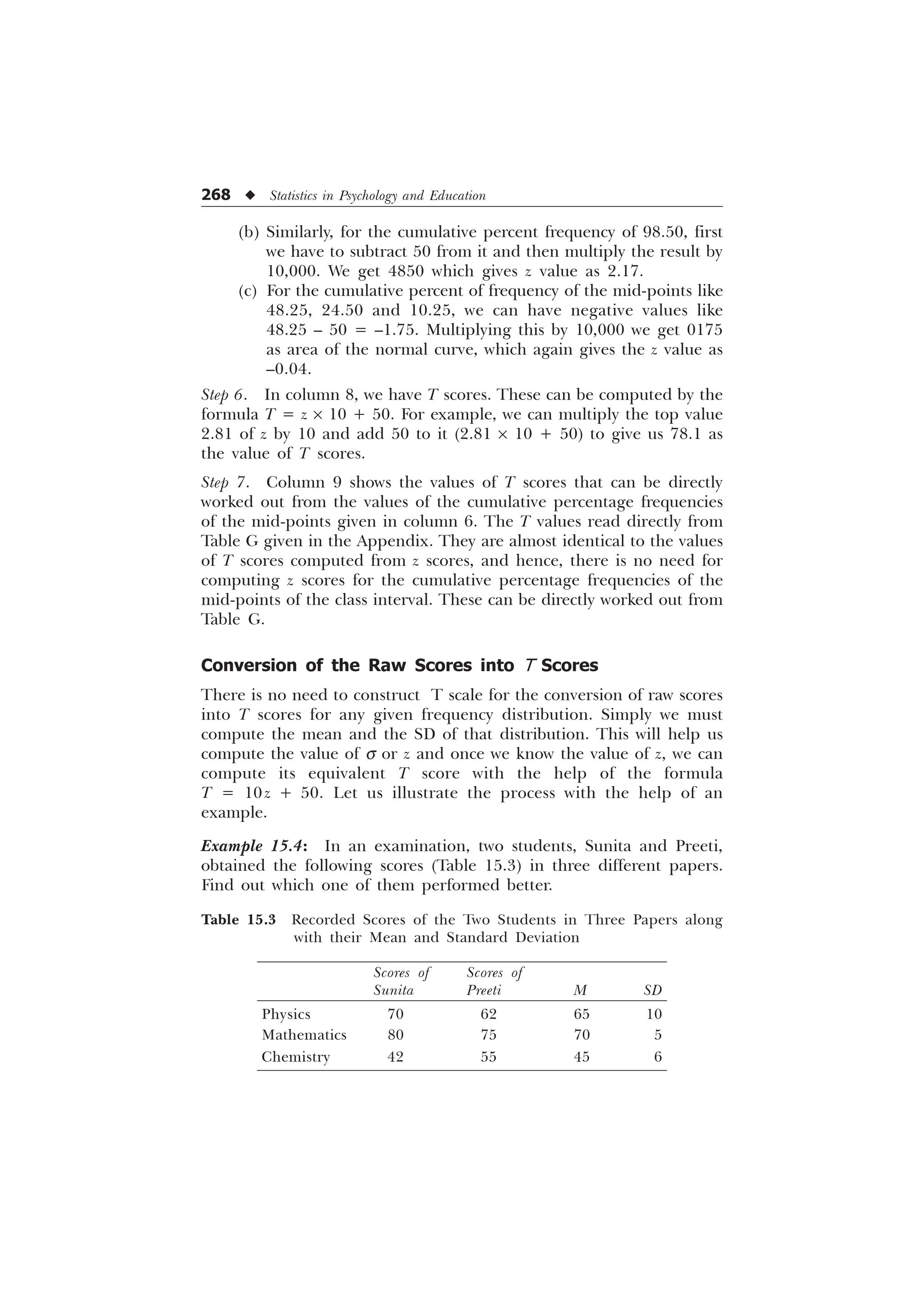

Figure 8.13 Showing the area covered by middle 60 percent.

+1s

(120)

+2s

(140)

+3s

(160)

M

(100)

–1s

(80)

–2s

(60)

–3s

(40)

30% 30%

Total

60%](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/stats-s-241206101830-e3d4cc67/75/Stats-S-K-Mangal-statistics-textook-in-pdf-137-2048.jpg)

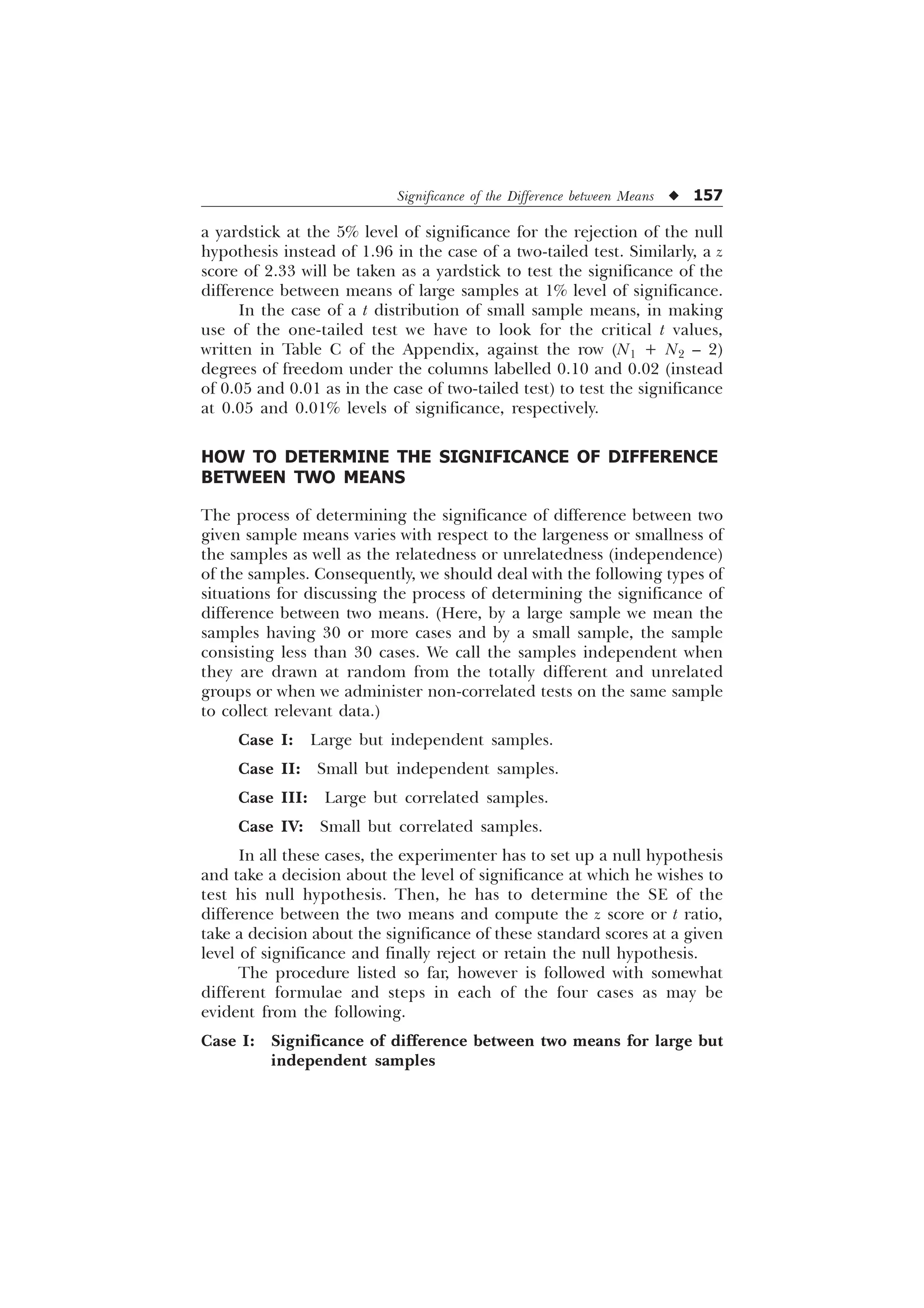

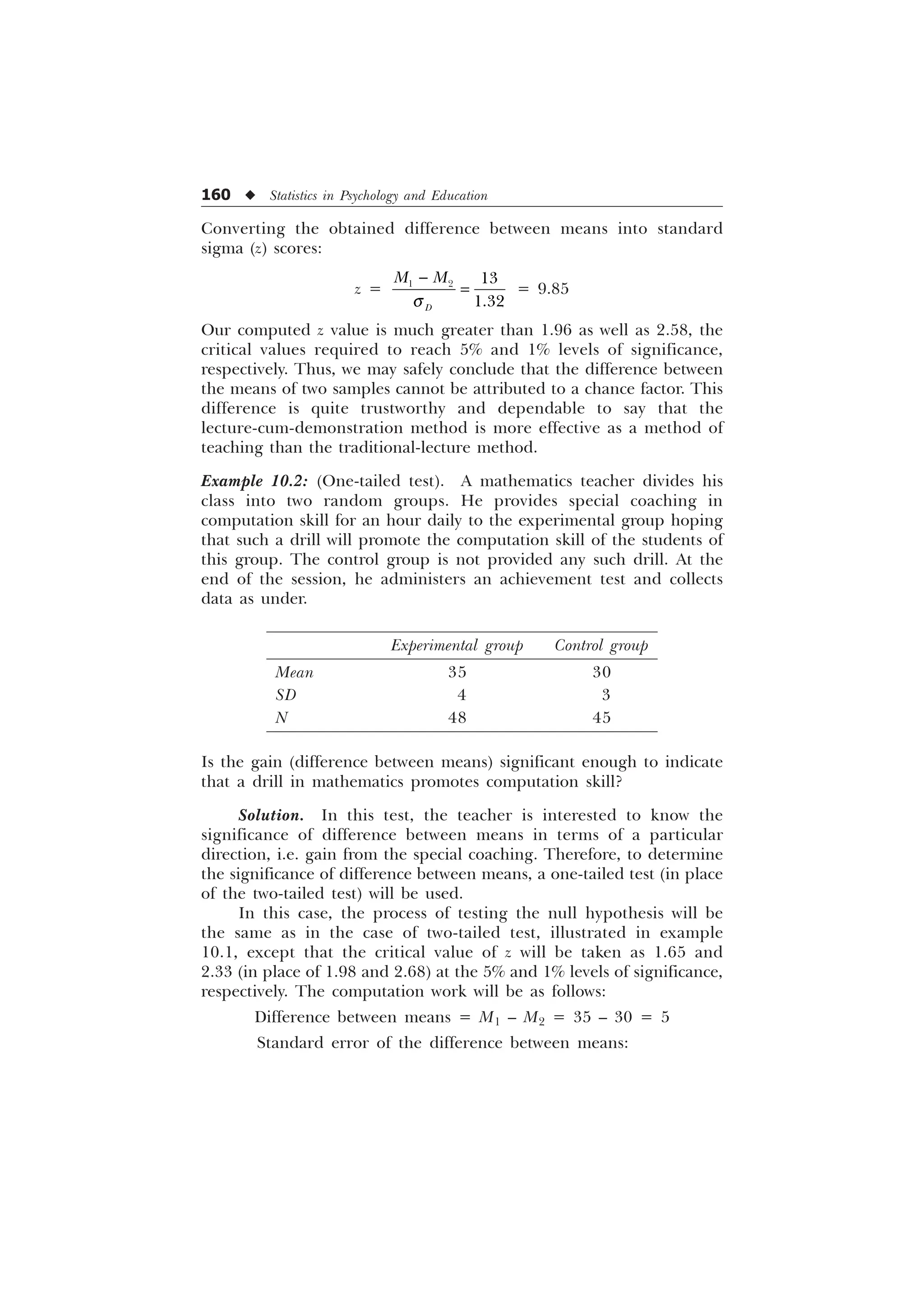

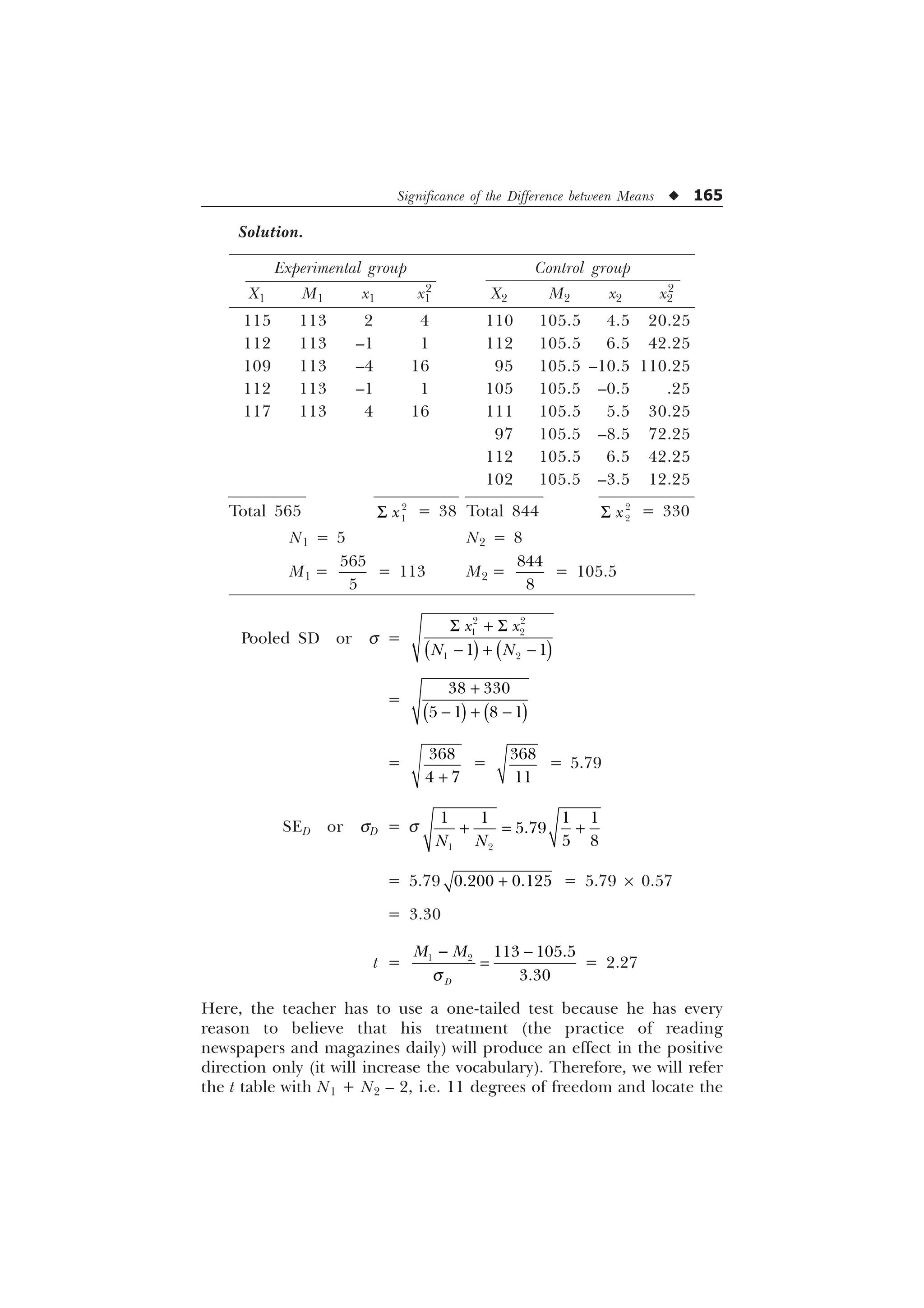

![158 u Statistics in Psychology and Education

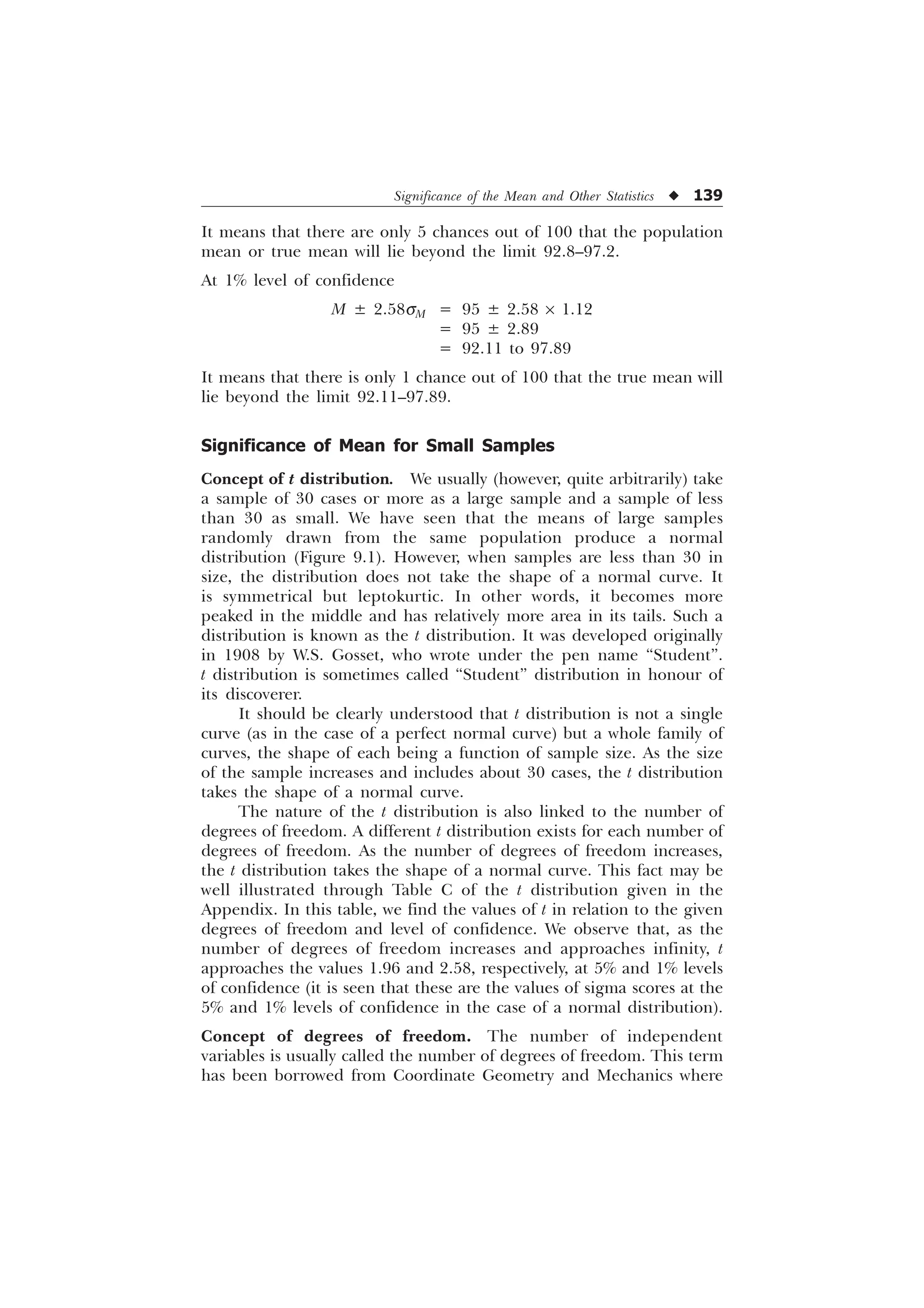

Step 1. To determine the SE of the difference between the means of two samples.

The formula for determining standard error of the difference between

means of two large but independent (non-correlated) samples is:

SED or sD =

0 0

T T

where

sM1

= SE of the means of the first sample

sM2

= SE of the means of the second sample

As we already know, sM1

and sM2

may be calculated by the formula

sM1

=

1

T

where s1 is the SD of the first sample and N1 is the size of the first

sample.

sM2

=

1

T

where s2 is the SD of the second sample and N2 is the size of the

second sample. In this way, the formula becomes

sD =

1 1

T

T

Step 2. To compute the z value for the difference in sample means. The

sampling distribution of difference between means in the case of large

samples is a normal distribution. This difference represented on the

base line of the normal curve may be converted into standard sigma

scores (z values) with the help of the following formula:

z =

T

'LIIHUHQFHEHWZHHQPHDQV

6WDQGDUGHUURURIGLIIHUHQFHEHWZHHQPHDQV

'

0 0

In this way, z represents the ratio of difference between the means to

the standard error of the difference between the means.

Step 3. Testing the null hypothesis at some pre-established level of significance.

At this stage, the null hypothesis, i.e. there exists no real difference

between the two sample means, is tested against its possible rejection at

5% or 1% level of significance in the following manner.

1. If the computed z value [i.e. z = (M1 – M2)/sD] is equal to 19.6

or greater than 1.96 (equal to or greater than 1.65 in the case

of a one-tailed test), we declare it significant for the rejection

of the null hypothesis at 5% level of significance.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/stats-s-241206101830-e3d4cc67/75/Stats-S-K-Mangal-statistics-textook-in-pdf-170-2048.jpg)

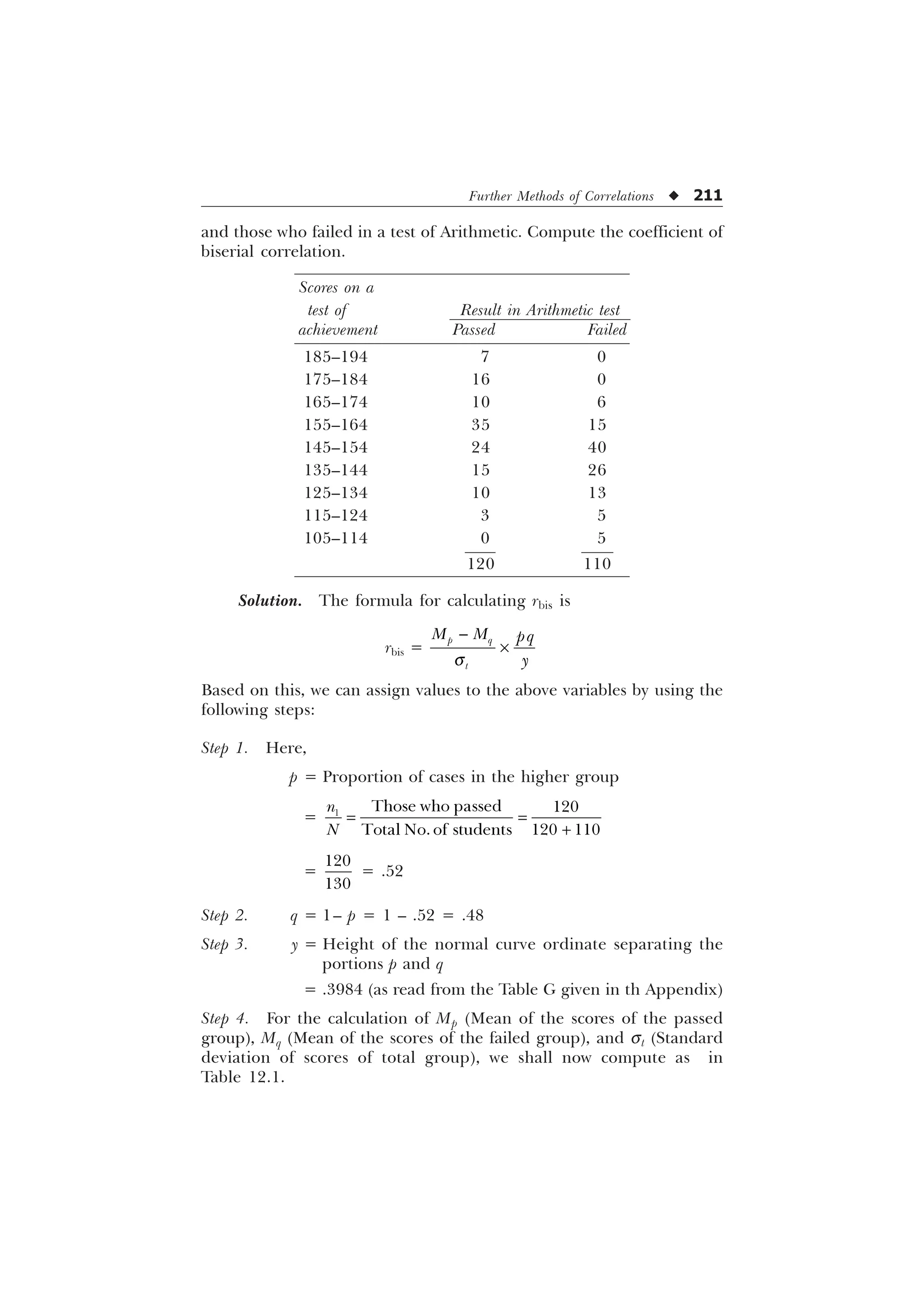

![Further Methods of Correlations u 213

Mp – Mq = 156.75 – 144.05 = 12.70

st = i

„ „

È Ø

É Ù

Ê Ú

I] I]

1 1

= 10

È Ø

É Ù

Ê Ú

= 10

–

–

=

– –

=

= 16.83

Step 5. Substitute the value of p, q, y, Mp, Mq and st in the following

formula:

rbis =

S T

W

0 0 ST

T

–

=

– –

–

=

– –

–

= 0.47

[Ans. Coefficient of biserial correlation, rbis = 0.47.]

Alternative Formula for rbis

The coefficient of biserial correlation, rbis, can also be computed with

the help of the following formula:

rbis =

S W

W

0 0 S

T

–

In this formula, we have to compute Mt (mean of the entire group) in

place of Mq.

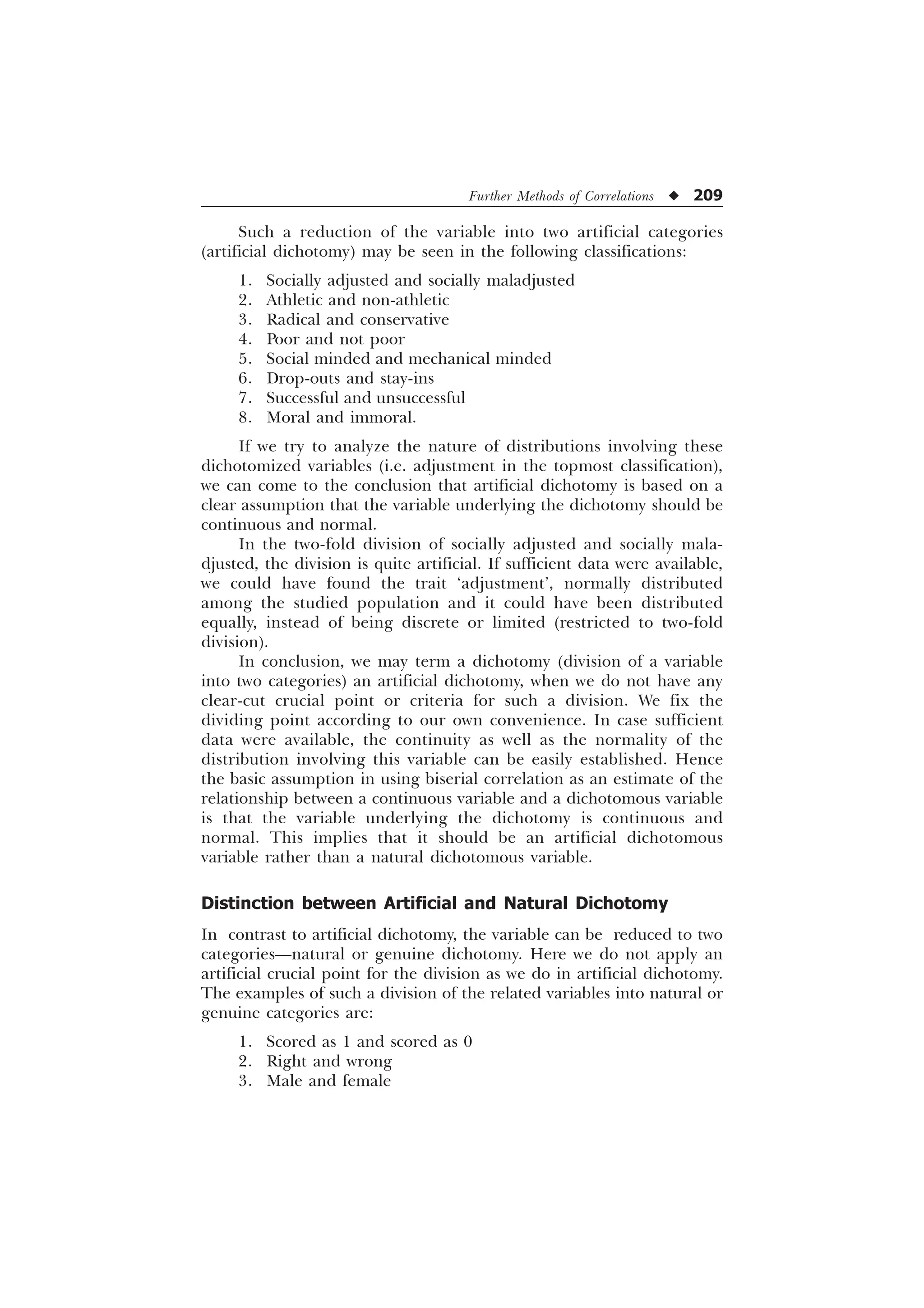

Characteristics of Biserial Correlation

The biserial correlation coefficient, rbis, is computed when one variable](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/stats-s-241206101830-e3d4cc67/75/Stats-S-K-Mangal-statistics-textook-in-pdf-225-2048.jpg)

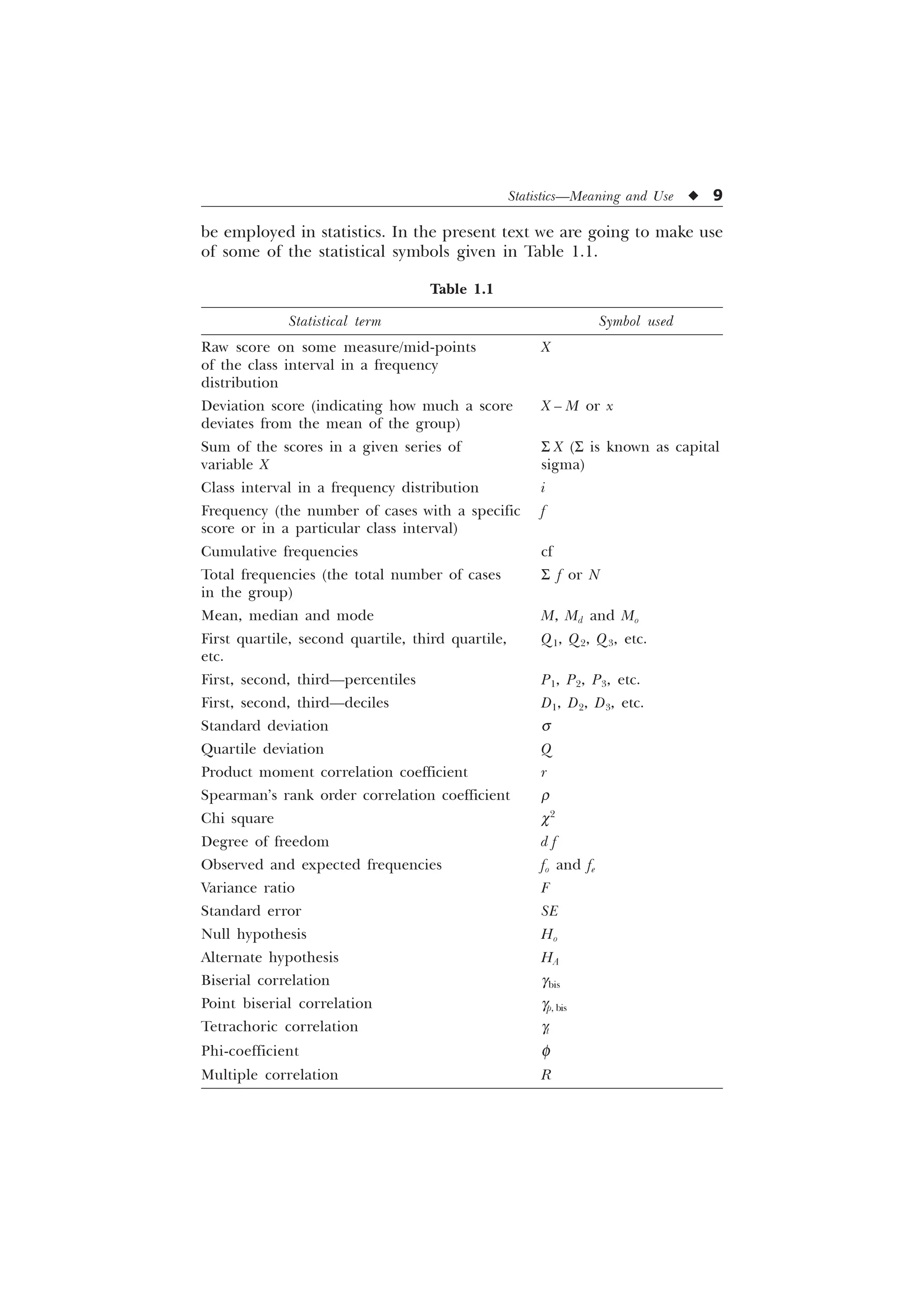

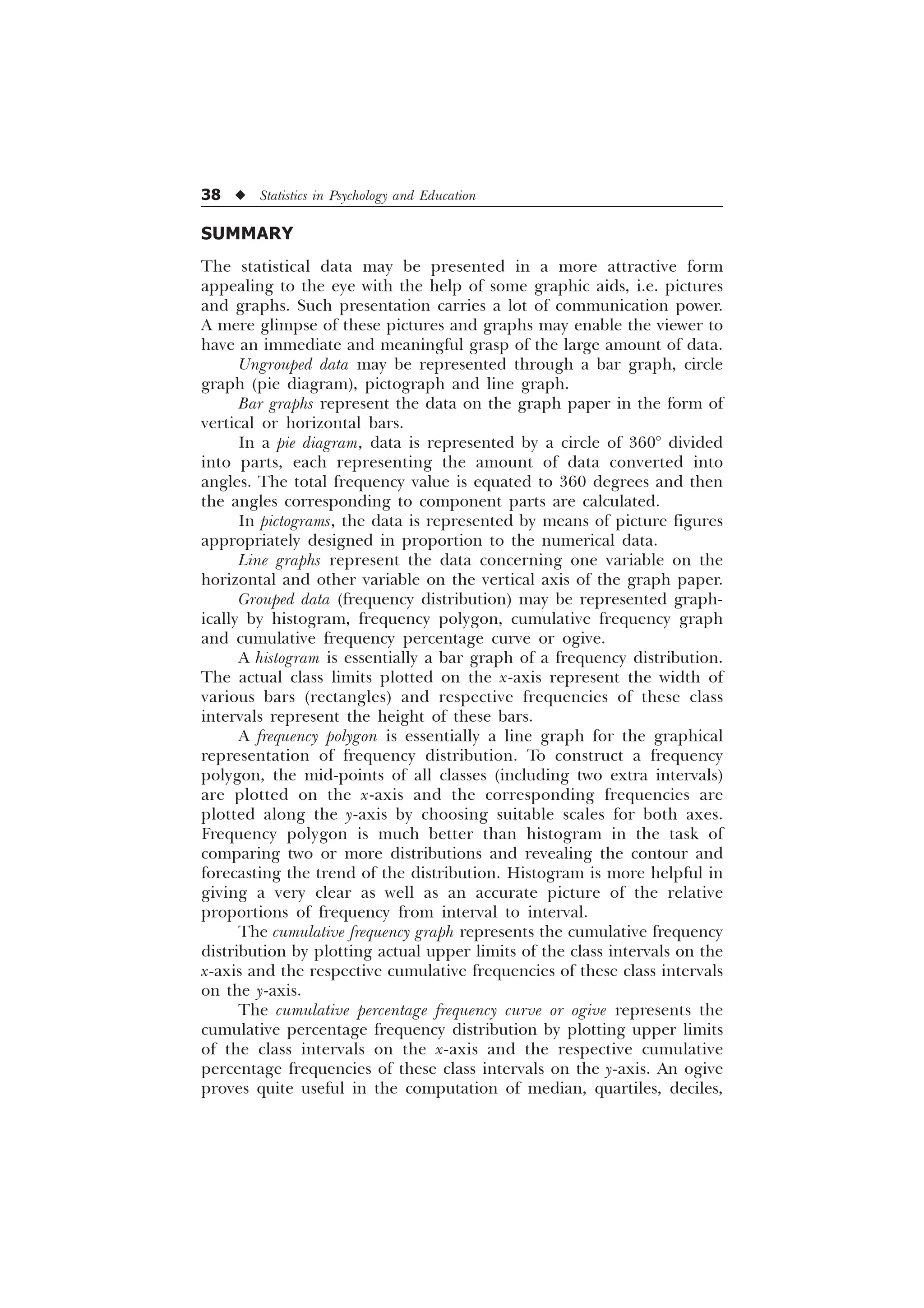

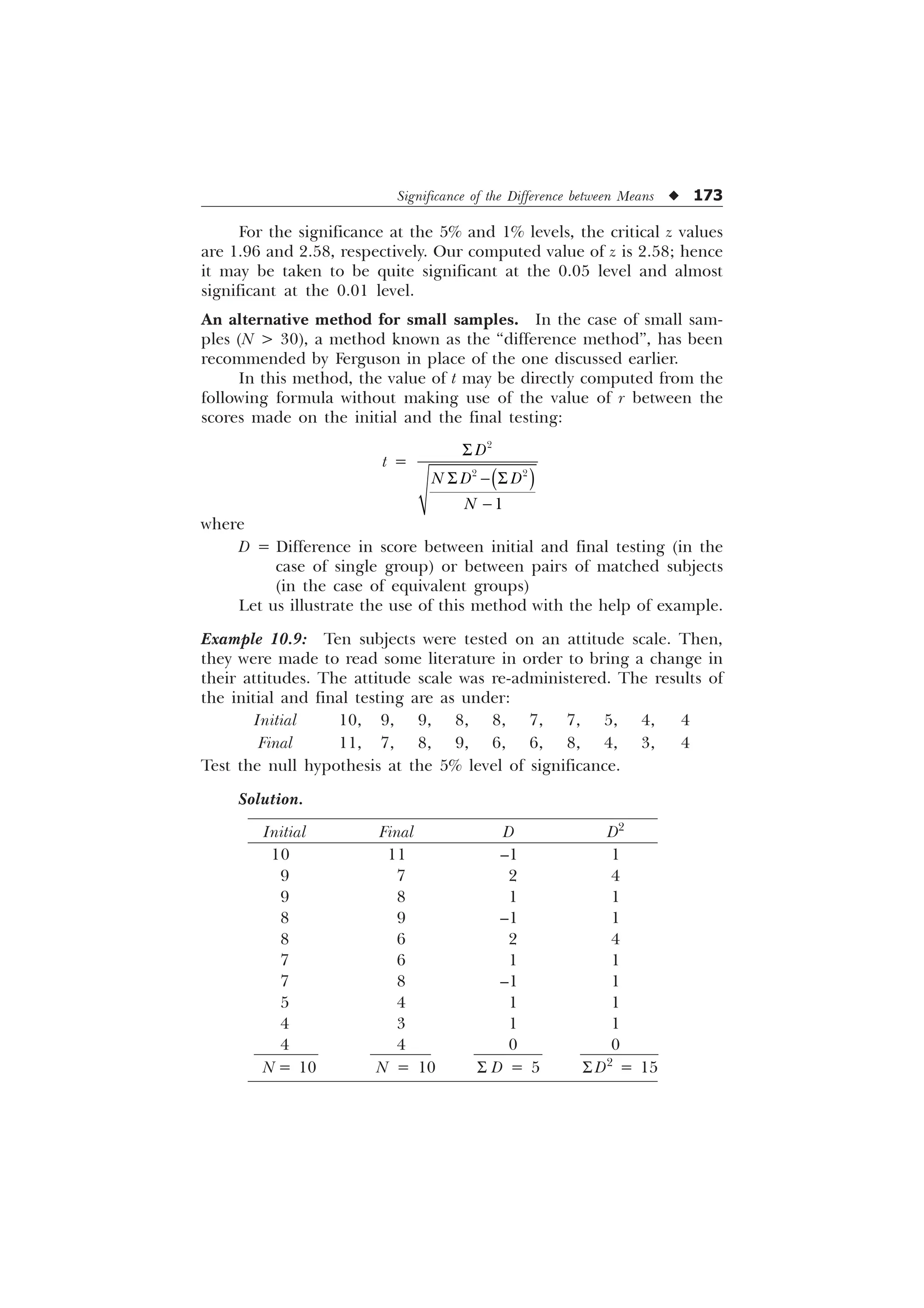

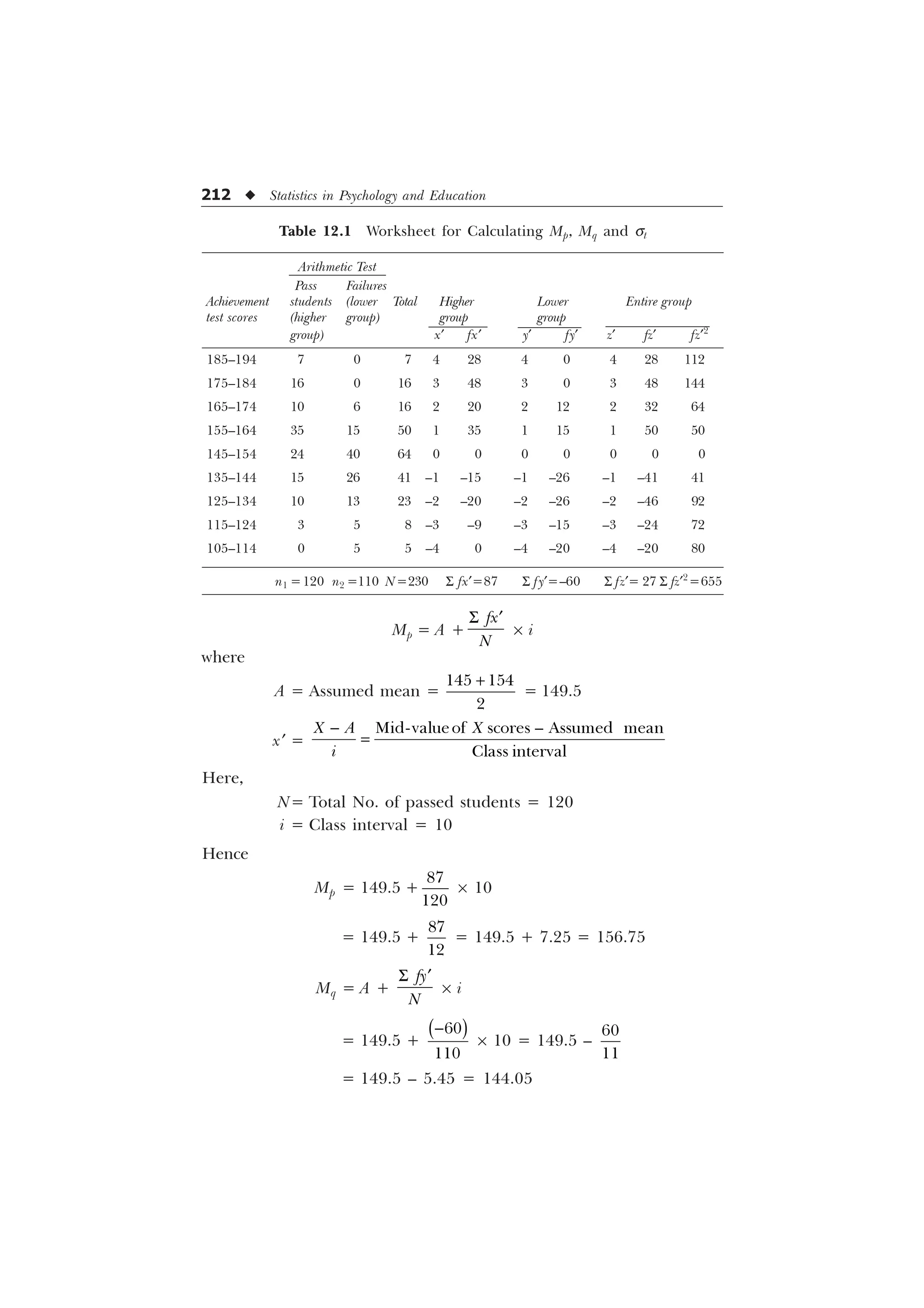

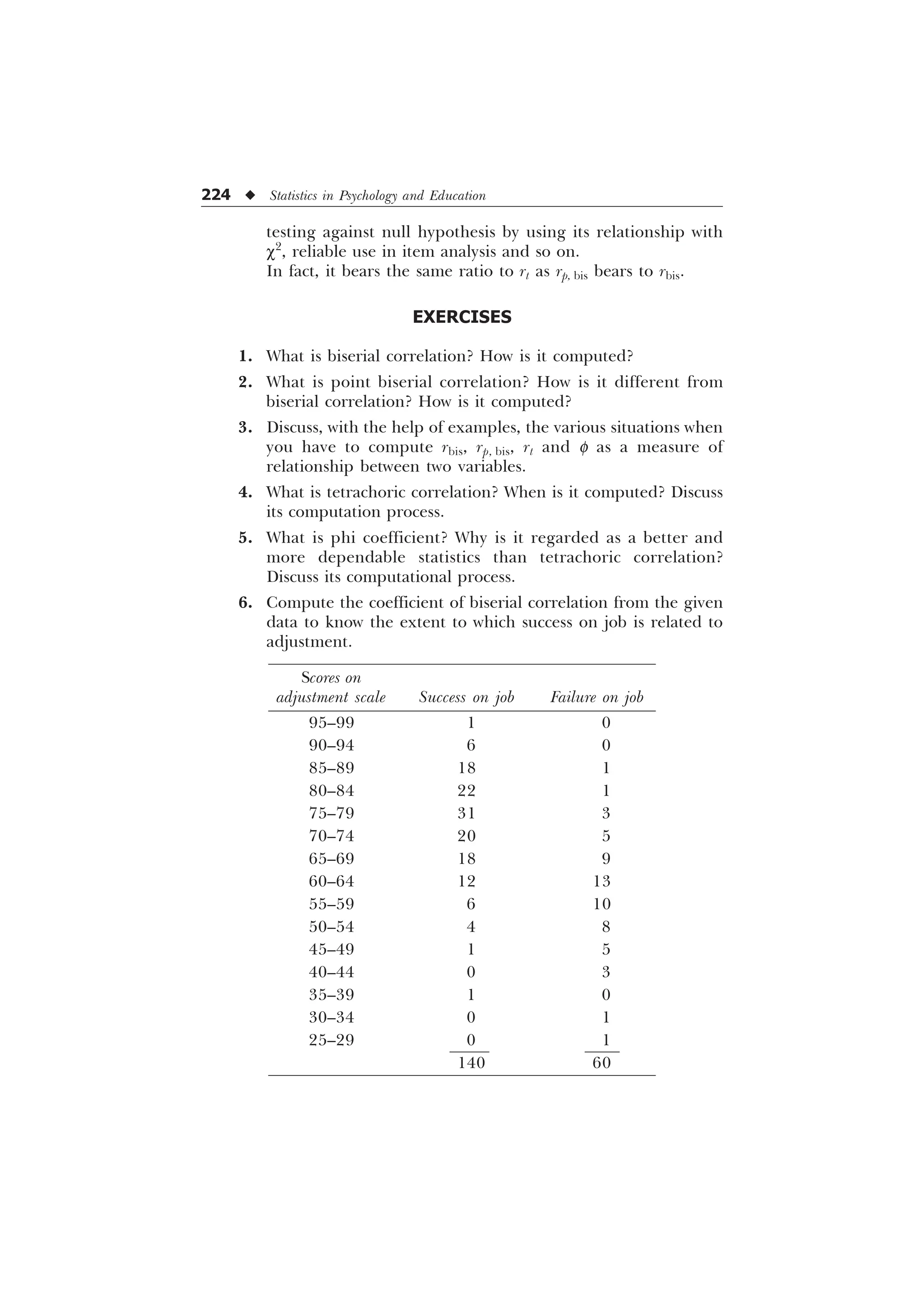

![216 u Statistics in Psychology and Education

Step 2. q = 1 – p = 1 – 0.46 = 0.54

Step 3. Calculation of Mp, Mt and st

The computation process is illustrated in Table 12.2

Table 12.2 Worksheet for Computation of Mp and st

Those who Those who

Scores responded responded Total x¢ fx¢ z¢ fz¢ fz¢2

on X rightly wrongly

70–74 3 0 3 5 15 5 15 75

65–69 6 1 7 4 24 4 28 112

60–64 6 2 8 3 18 3 24 72

55–59 5 4 9 2 10 2 18 36

50–54 6 2 8 1 6 1 8 8

45–49 7 6 13 0 0 0 0 0

40–44 6 8 14 –1 –6 –1 –14 14

35–39 3 6 9 –2 –6 –2 –18 36

30–34 3 9 12 –3 –9 –3 –36 108

25–29 1 4 5 –4 –4 –4 –20 80

20–24 0 12 12 –5 0 –5 –60 300

n1=46 n2 = 54 N=100 S fx¢=48 S fz¢=–55 S fz¢2

=841

Mp = A +

I[

Q

6 „

´ i = 47 +

´ 5 = 47 + 5.2 = 52.2

(Here, A = Assumed mean =

= 47, i = 5 and n1 = 46)

Mt = A +

I]

1

6 „

´ i= 47 +

´ 5 = 47 – 2.75 = 44.2

st = i

I] I]

1 1

6 6

„ „

È Ø

É Ù

Ê Ú

= 5

È Ø

É Ù

Ê Ú

= 5

–

–

=

=

=

= 14.236

rp,bis =

S W

W

0 0

S T

T

=

=

= = 0.52

[Ans. Point biserial correlation coefficient rp,bis = 0.52.]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/stats-s-241206101830-e3d4cc67/75/Stats-S-K-Mangal-statistics-textook-in-pdf-228-2048.jpg)

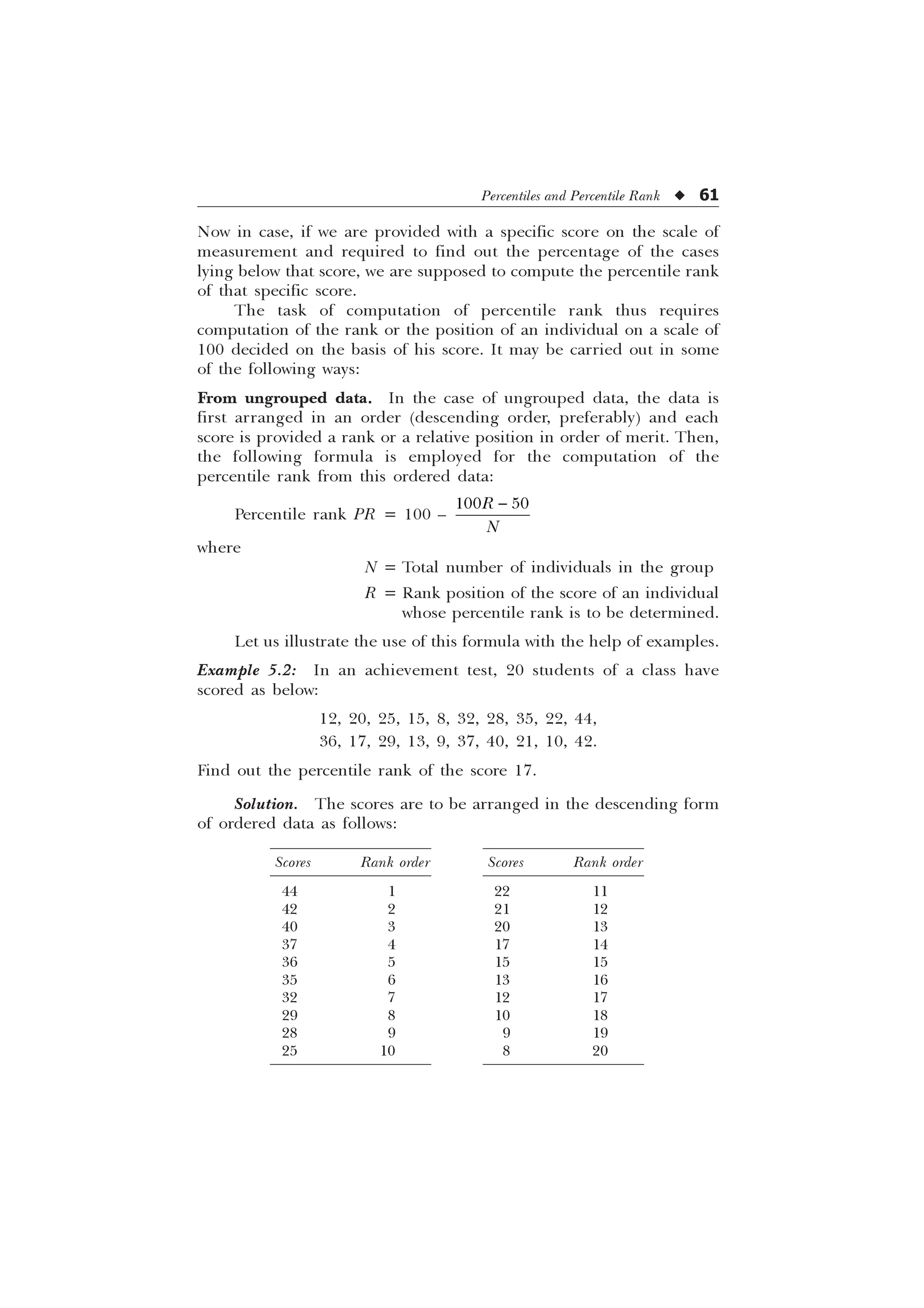

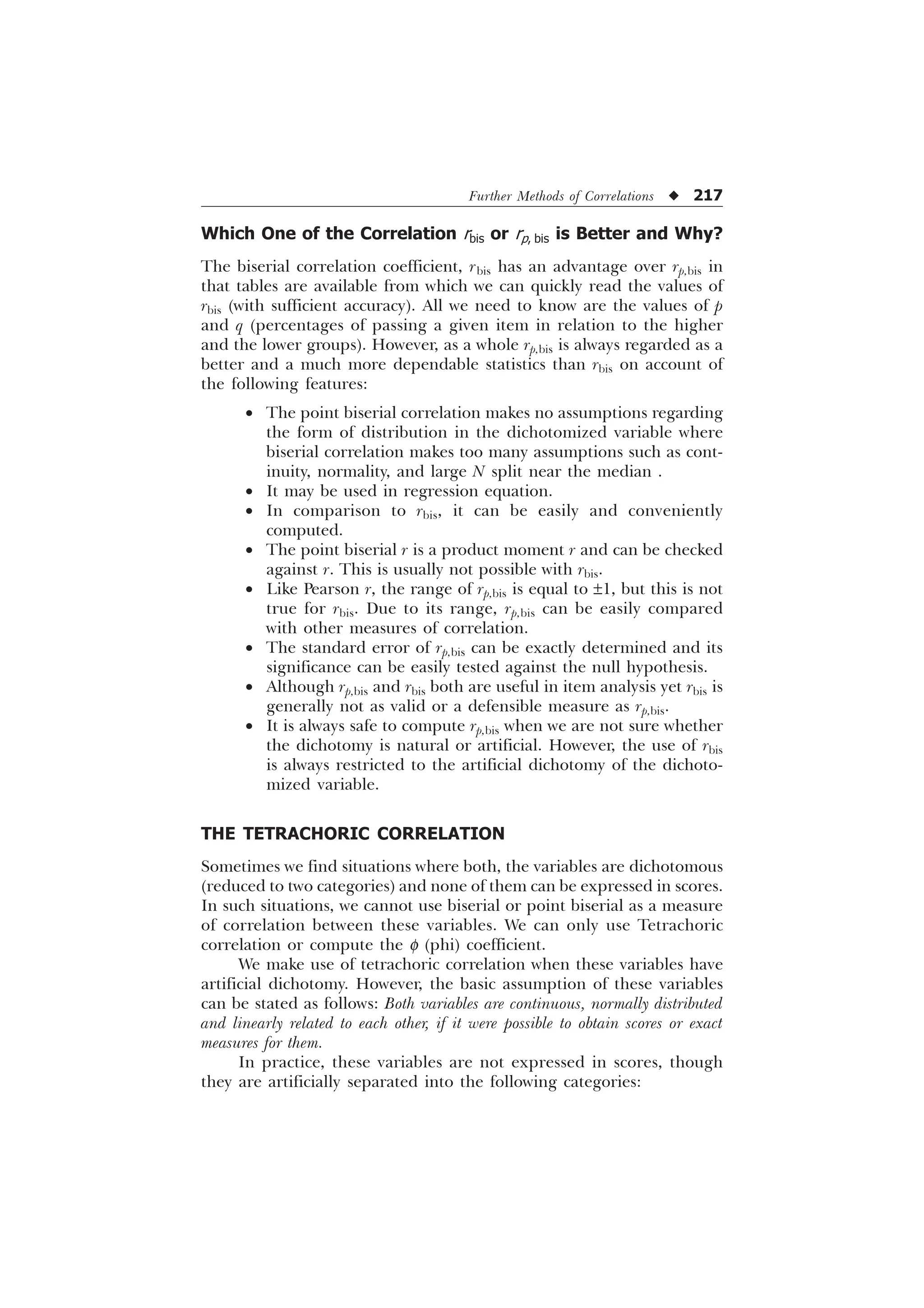

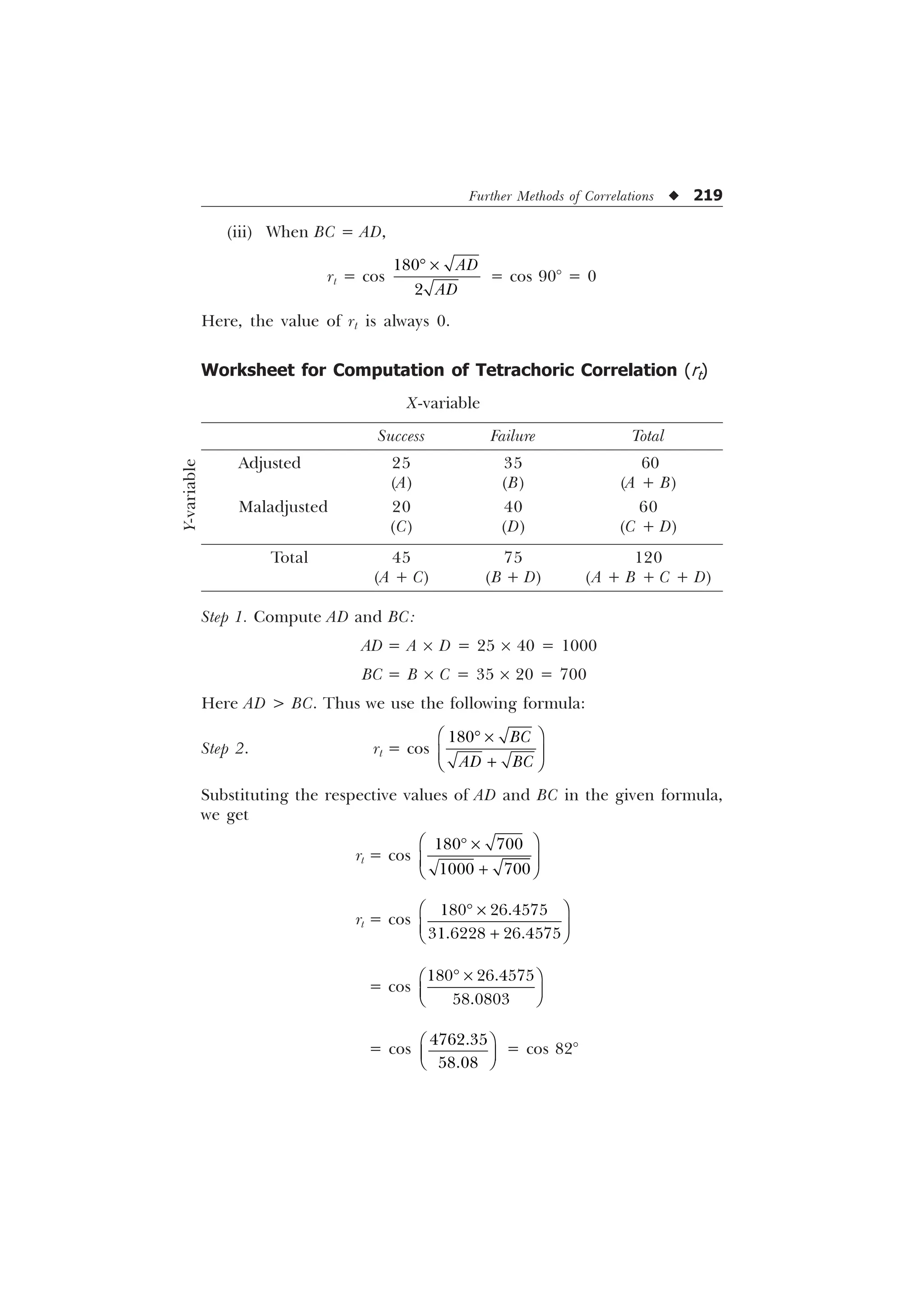

![220 u Statistics in Psychology and Education

Step 3. Convert cos 82° into rt. (It can be done directly with the help

of Table H given in the Appendix.) Then,

rt = 0.139

[Ans. Tetrachoric correlation = 0.139.]

Limitations of the general formula rt = cos

%

$' %

È Ø

’ –

É Ù

Ê Ú

= cos

$' %

’

The foregoing formula shows good results in computation of rt

only when (i) N is large and (ii) the splits into dichotomized variables

are not far removed from the median.

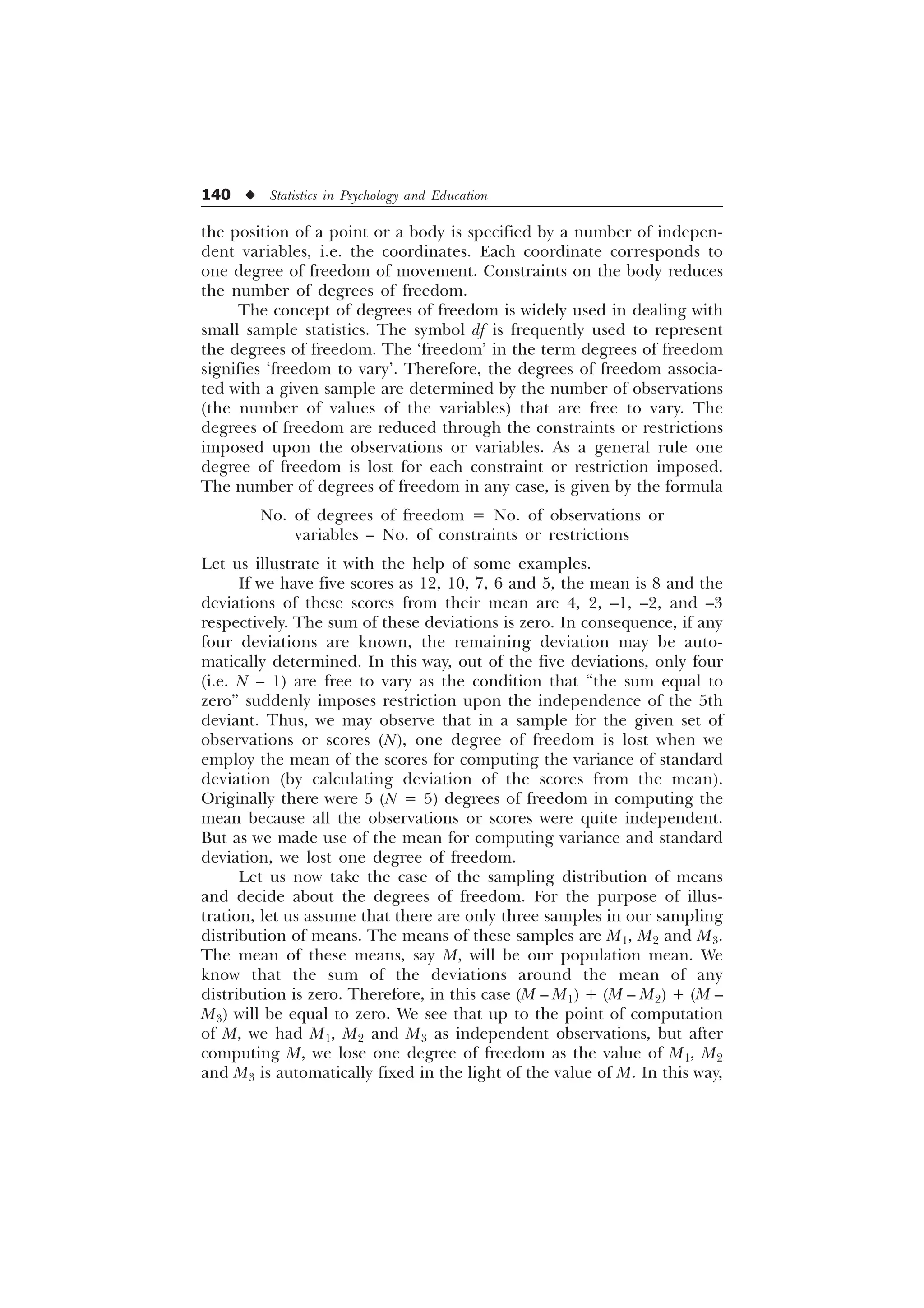

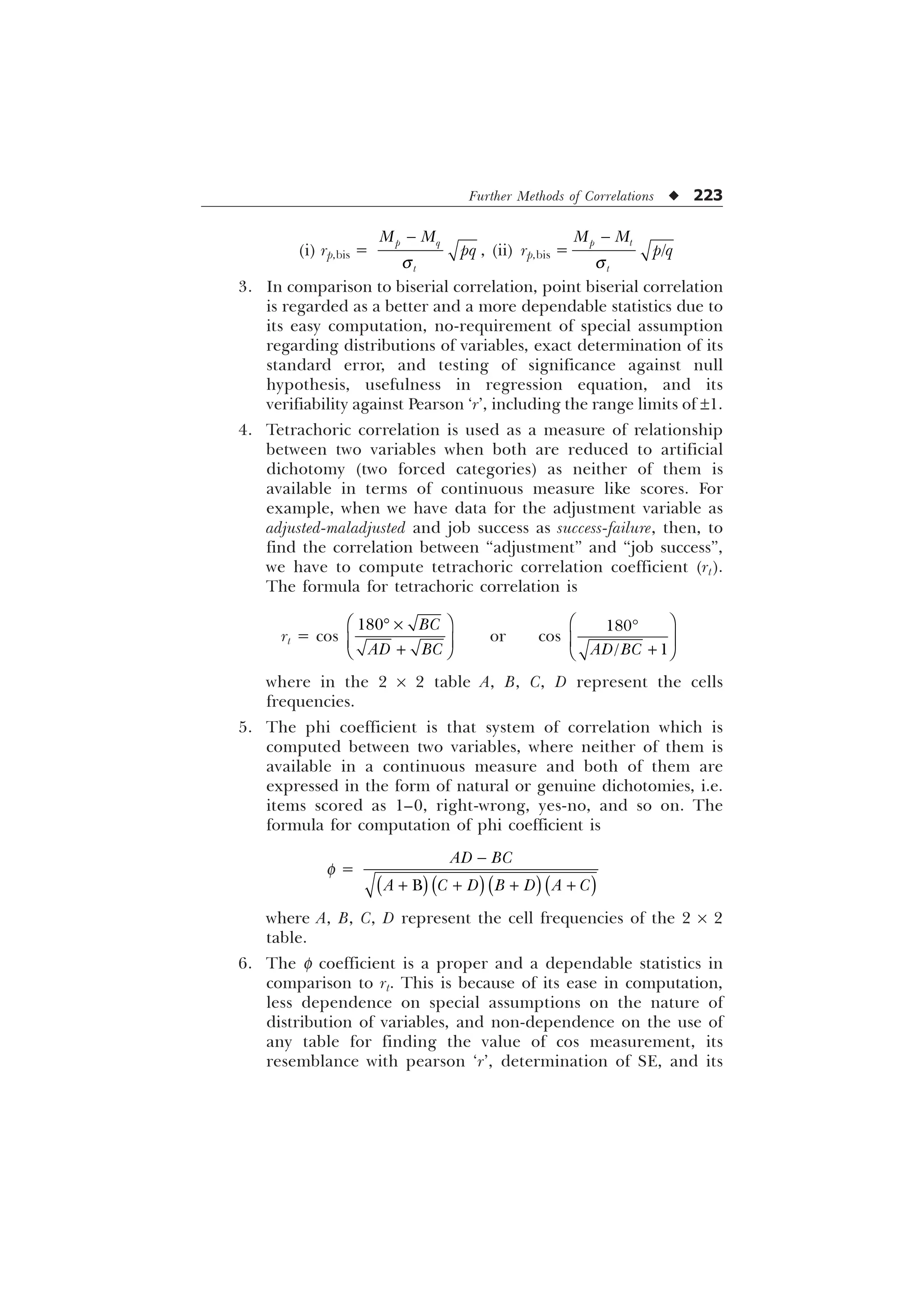

THE PHI (f) COEFFICIENT

In studies where we have to compute correlation between two such

variables which are genuinely dichotomous, it is the f coefficient that is

computed. Generally, its computation may involve the following

situations:

1. When the classification of the variables into two categories is

entirely and truly discrete, we are not allowed to have more

than two categories, i.e. living vs. dead, employed vs. not

employed, blue vs. brown eyes and so on.

2. When we have test items which are scored as Pass-Fail,

True-False, or opinion and attitude responses, which are

available in the form of yes-no, like-dislike, agree-disagree

etc., no other intermediate type of responses is allowed.

3. With such dichotomized variables which may be continuous

and may even be normally distributed, but are treated in

practical operations as if they were genuine dichotomies, e.g.

test items that are scored as either right or wrong, 1 and 0

and the like.

Computation of Phi (f) Coefficient

FORMULA. The formula for computation of f coefficient is

f =

%

$' %

$ ' % ' $](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/stats-s-241206101830-e3d4cc67/75/Stats-S-K-Mangal-statistics-textook-in-pdf-232-2048.jpg)

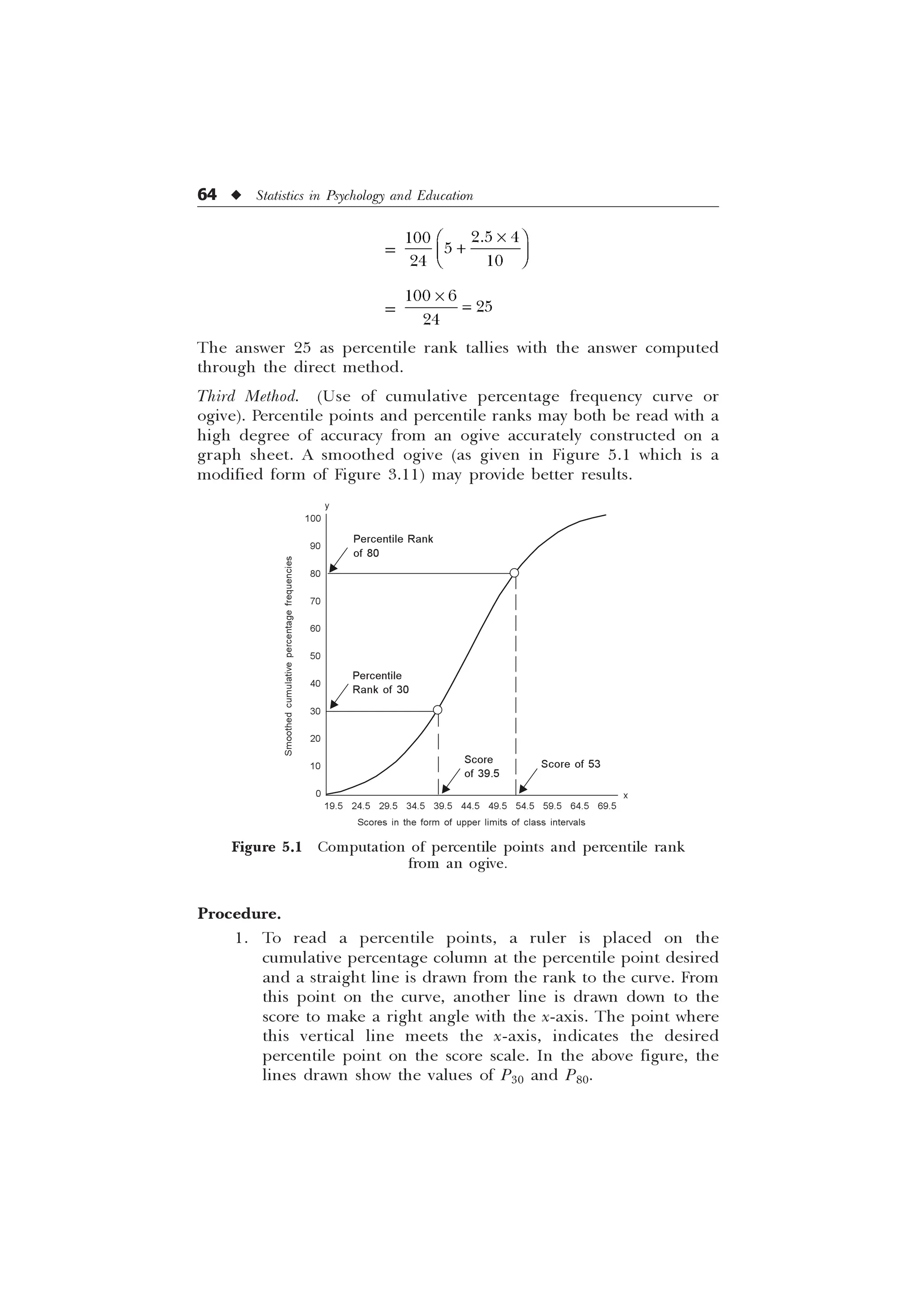

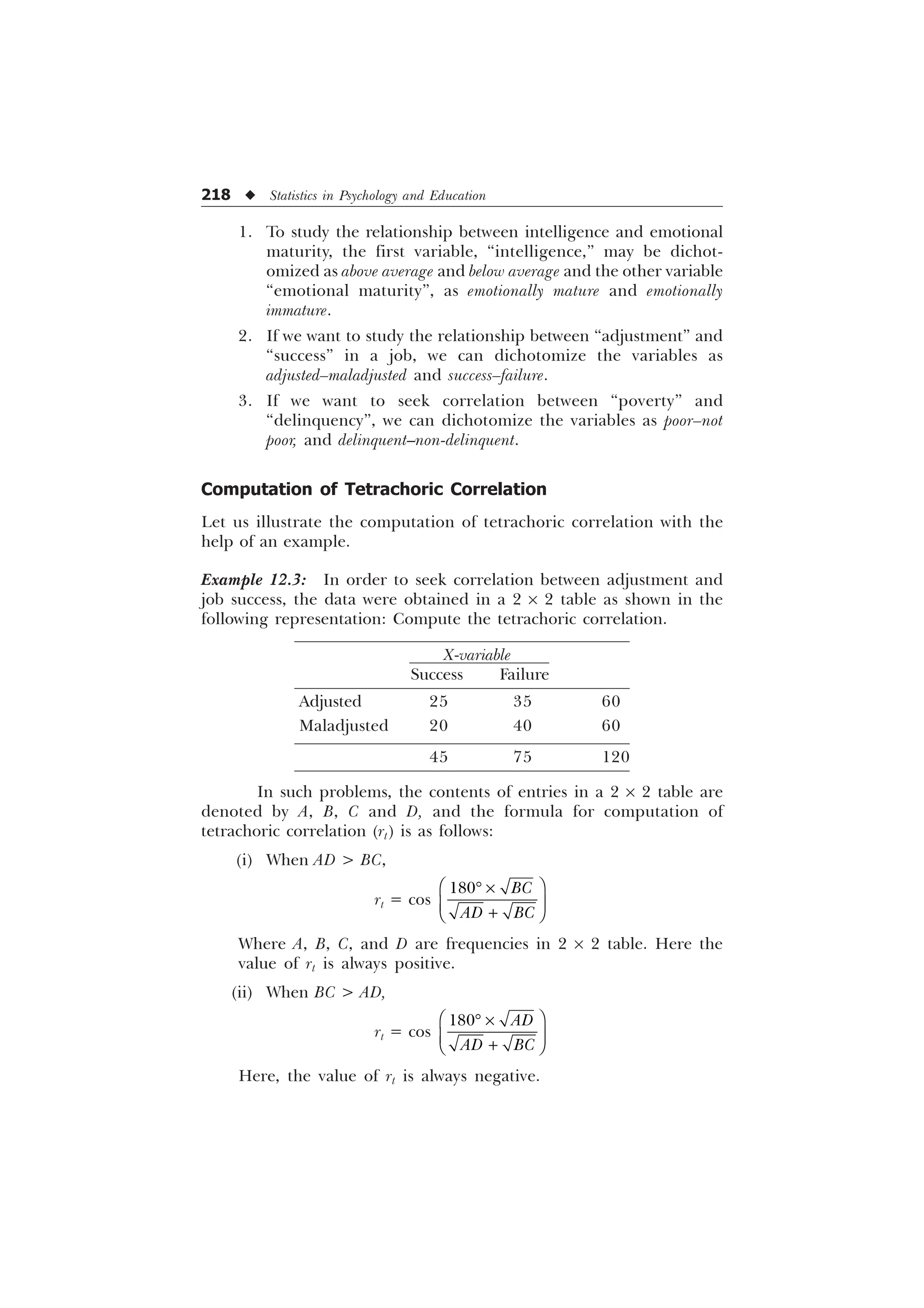

![Further Methods of Correlations u 221

where A, B, C, D represent the frequencies in the cells of the following

2 ´ 2 table:

X-variable

Yes No Total

Yes A B A + B

No C D C + D

Total A + C B + D A + B + C + D

Let us illustrate the use of forgoing formula with the help of an

example.

Example 12.4: There were two items X and Y in a test which were

responded by a sample of 200, given in the 2 ´ 2 table. Compute the

phi coefficient of correlation between these two items.

Solution.

Item X

Yes No Total

Yes 55 45 100

(A) (B) (A + B)

No 35 65 100

(C) (D) (C + D)

Total 90 110 200

(A + C) (B + D) (A + B + C + D)

FORMULA.

f coefficient =

%

$' %

$ ' % ' $

Substituting the respective values in the formula, we obtain

f =

– –

– – –

=

f =

= .201

[Ans. f coefficient = 0.201.]

Y-variable

Item

Y](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/stats-s-241206101830-e3d4cc67/75/Stats-S-K-Mangal-statistics-textook-in-pdf-233-2048.jpg)

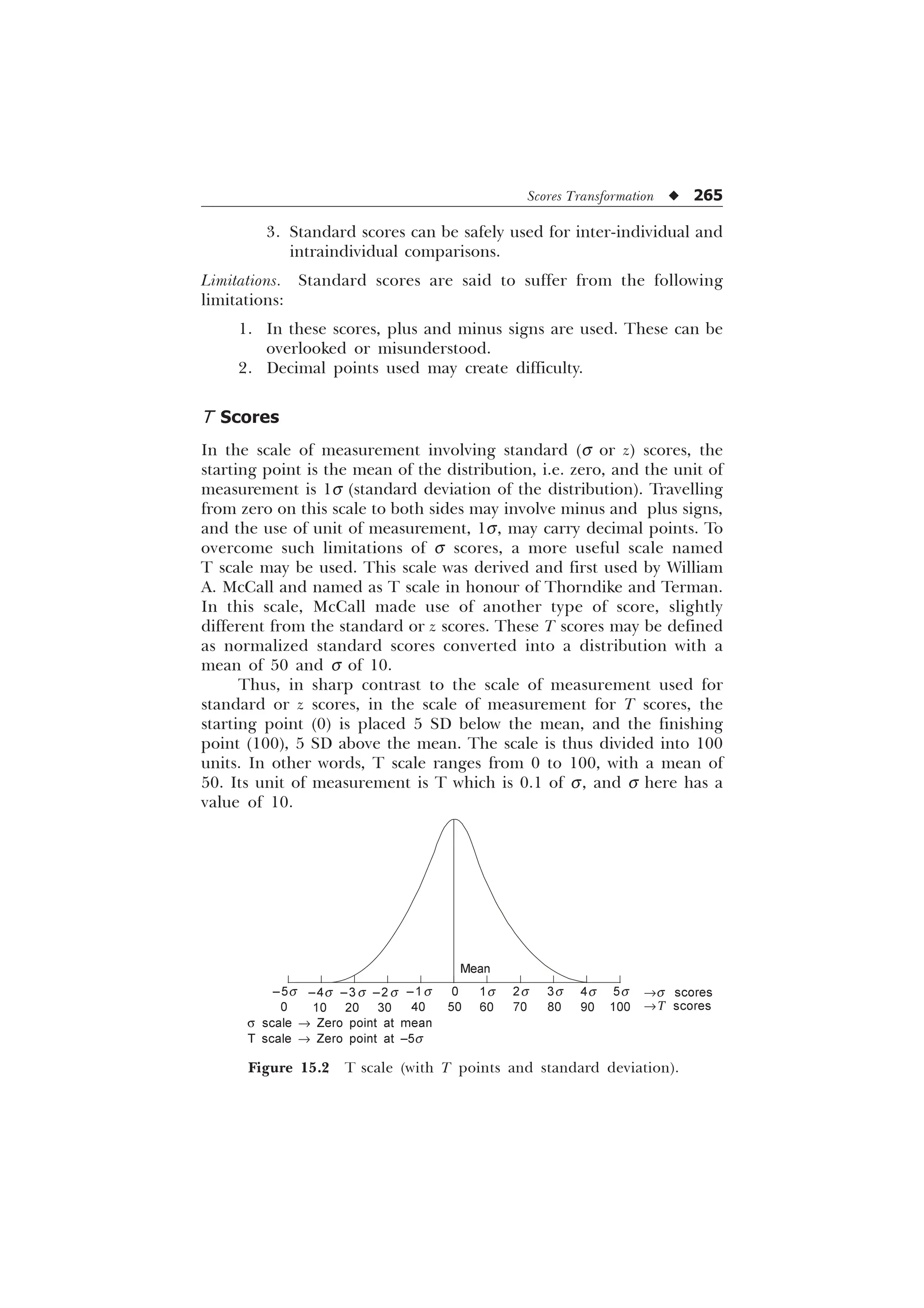

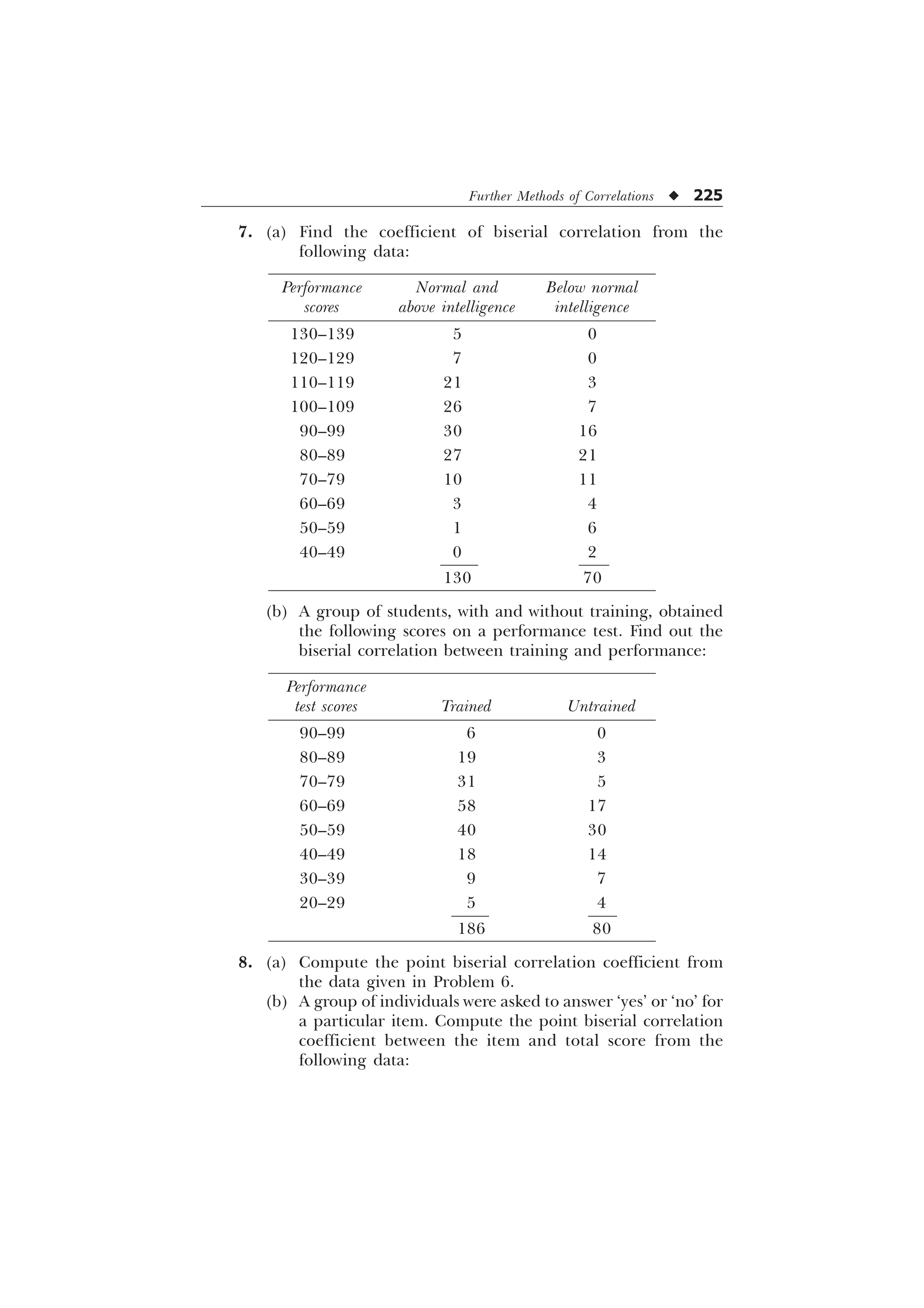

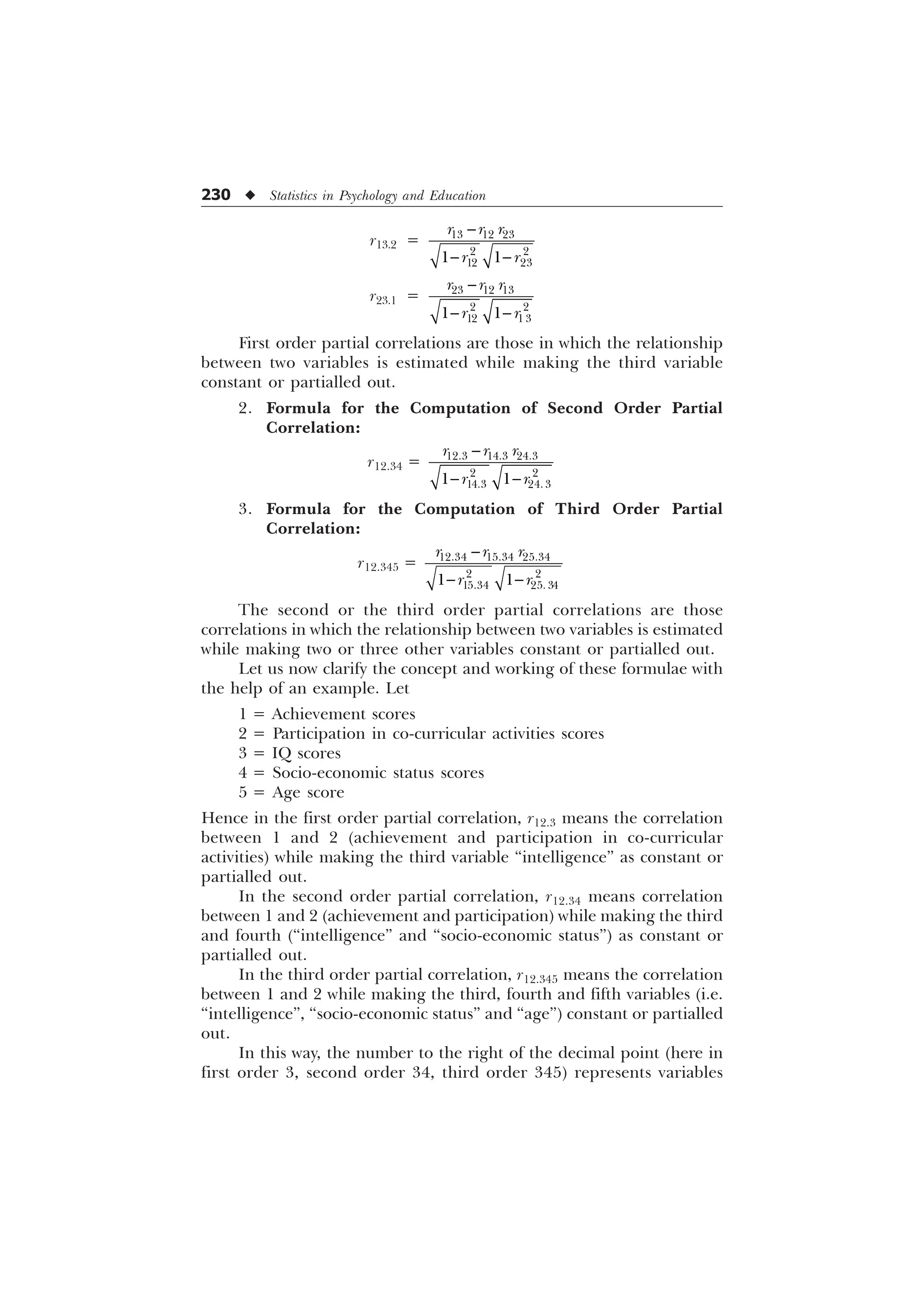

![Partial and Multiple Correlation u 231

whose influence is ruled out and the number to the left (here 12)

represents those two variables whose relationship needs to be estimated.

It is also clear from the given formulae that, for computation of

second order correlations, all the necessary first order correlations have

to be computed, and for the third order correlations, the second order

correlations must be known.

Let us now illustrate the process of computation of partial

correlation with the help of examples.

Example 13.1: From a certain number of schools in Delhi, a sample of

500 students studying in classes IX and X was taken. These students were

evaluated in terms of their academic achievement and participation in

co-curricular activities. Their IQ’s were also tested. The correlation

among these three variables was obtained and recorded as follows:

r12 = 0.18, r23 = 0.70, r13 = 0.60

Find out the independent correlation between the main (first two)

variables—academic achievement and participation—in co-curricular

activities.

Solution. The independent and reliable correlation between

academic achievement and participation in co-curricular activities—the

main two variables—can be found by computing partial correlation

between these two variables, i.e. by computing r12.3 (keeping constant the

third variable)

r12.3 =

U U U

U U

Substituting the given value of correlation in the foregoing formula, we

obtain

r12.3 =

–

– –

=

=

–

=

= 0.67

[Ans. Partial correlation = 0.67.]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/stats-s-241206101830-e3d4cc67/75/Stats-S-K-Mangal-statistics-textook-in-pdf-243-2048.jpg)

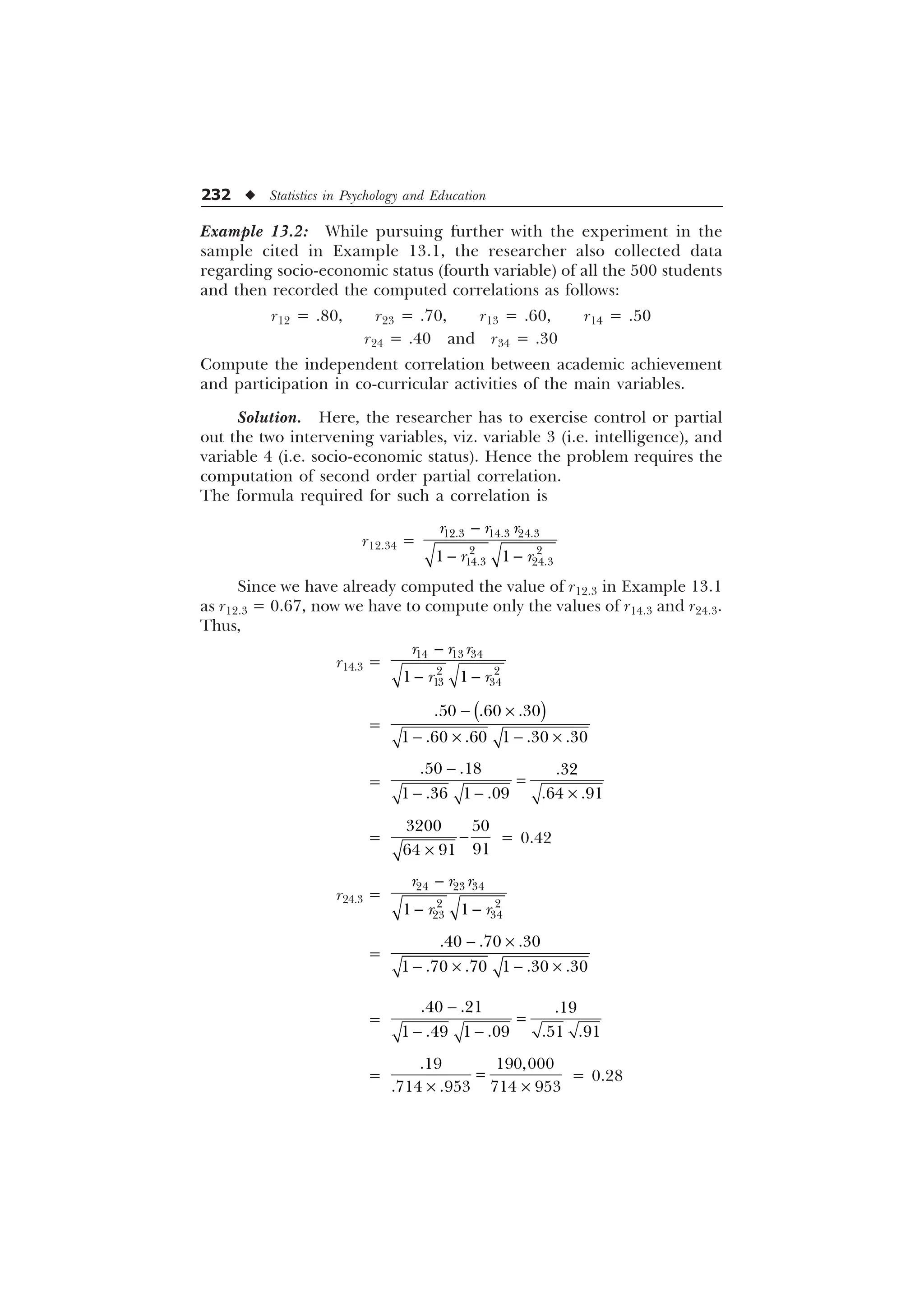

![Partial and Multiple Correlation u 233

r12.34 =

–

– –

=

=

–

=

= .64

[Ans. Partial correlation = 0.64.]

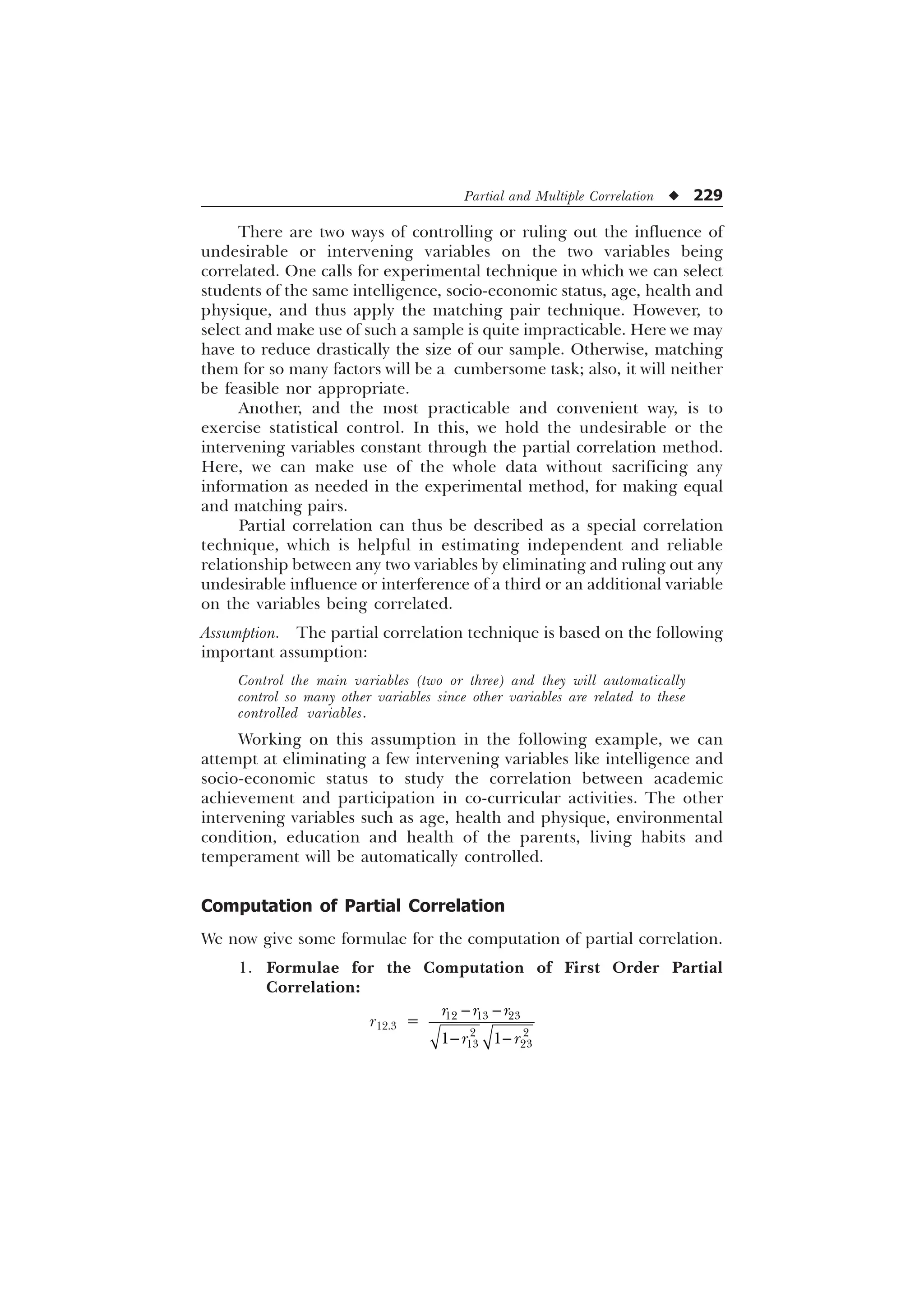

Application of Partial Correlation

Partial correlation can be used as a special statistical technique for

eliminating the effects of one or more variables on the two main

variables, for which we want to compute an independent and a reliable

measure of correlation. Besides its major advantage lies in the fact that

it enables us to set up a multiple regression equation (see Chapter 14)

of two or more variables, by means of which we can predict another

variable or criterion.

Significance of Partial Correlation Coefficient

The significance of the first and the second order partial correlation ‘r’

can be tested easily by using the ‘t’ distribution

t = r

1 .

U

where

K = Order of partial r

r = Value of partial correlation

N = Total frequencies in the sample study

Therefore,

Degree of freedom = N – 2 – K

NEED AND IMPORTANCE OF MULTIPLE CORRELATION

In many studies related to education and psychology, we find that a

variable is dependent on a number of other variables called independent

variables. For example, if we take the case of one’s academic achievement,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/stats-s-241206101830-e3d4cc67/75/Stats-S-K-Mangal-statistics-textook-in-pdf-245-2048.jpg)

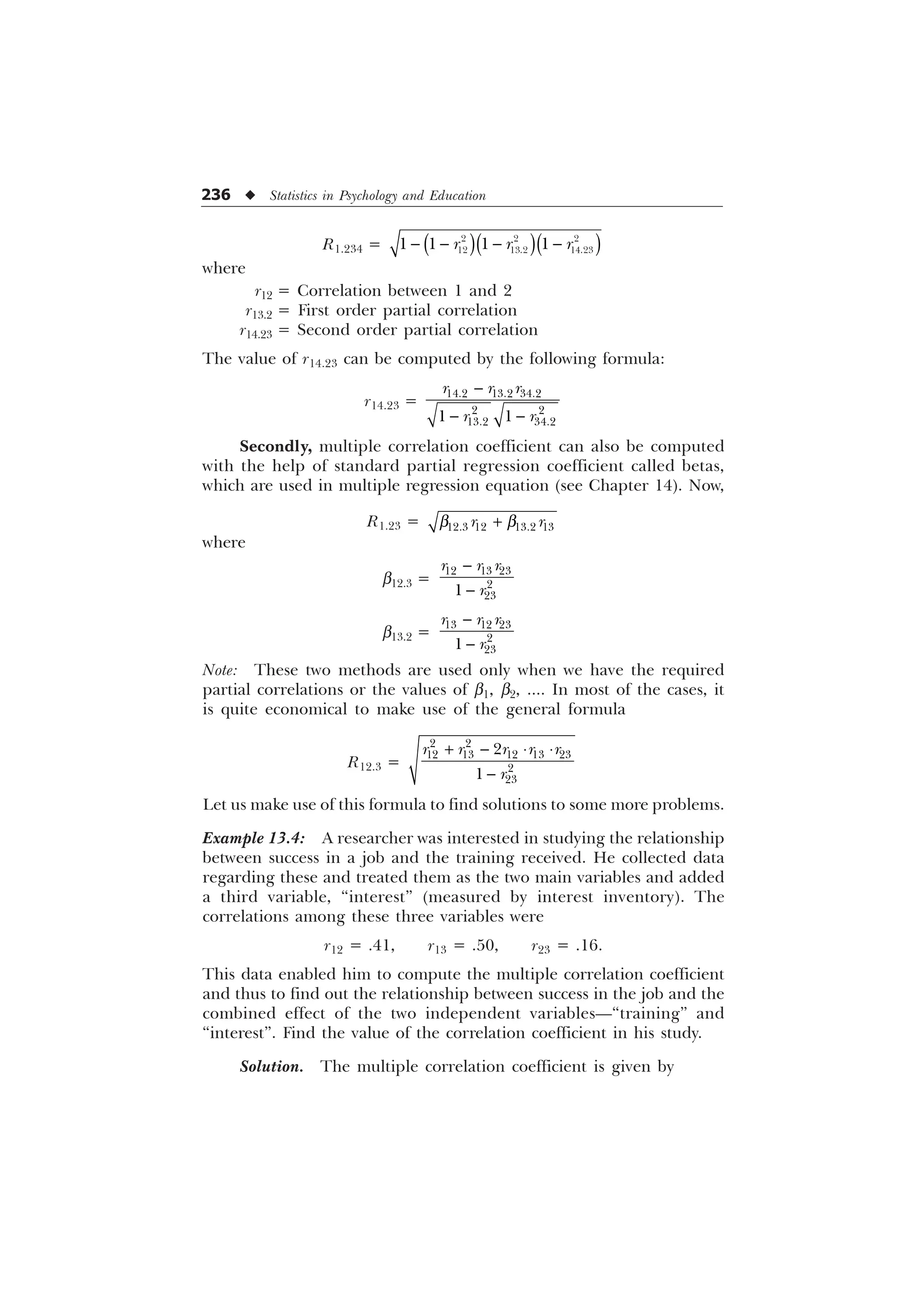

![Partial and Multiple Correlation u 235

Example 13.3: In a study, a researcher wanted to know the impact of

a person’s intelligence and his socio-economic status on his academic

success. For computing the coefficient of multiple correlation, he

collected the required data and computed the following inter-

correlations:

r12 = 0.60, r13 = 0.40, r23 = 0.50

where 1, 2, 3 represent the variables “academic success”, “intelligence”

and “socio-economic status”, respectively. In this case, find out the

required multiple correlation coefficient.

Solution. The multiple correlation coefficient

R1.23 =

¹ ¹

U U U U U

U

Substituting the respective values of r12, r13 and r23 in the above formula,

we get

R1.23 =

– – –

=

[Ans. Multiple correlation coefficient = 0.61.]

Other Methods of Computing Coefficient of Multiple

Correlation

Multiple correlation coefficient can also be computed by other means

like below.

First, it can be done with the help of partial correlation. Thus,

R1.23 =

U U

In this formula, to understand the relationship between variable 1 and

the combined effect of variables 2 and 3, we compute the multiple

correlation coefficient. The formula requires the values of r12

(correlation between 1 and 2) and the partial correlation r13.2, which can

be computed by using the formula

r13.2 =

U U U

U U

However, in case if there are four variables instead of three, then

we can compute the multiple correlation coefficient as](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/stats-s-241206101830-e3d4cc67/75/Stats-S-K-Mangal-statistics-textook-in-pdf-247-2048.jpg)

![Partial and Multiple Correlation u 237

R1.23 =

U U U U U

U

=

– – –

=

=

= 0.601

[Ans. Multiple correlation coefficient = 0.601.]

Example 13.5: One thousand candidates appeared for an entrance test.

The test had some sub-tests, namely, general intelligence test,

professional awareness test, general knowledge test and aptitude test. A

researcher got interested in knowing the impact or the strength of the

association of any two sub-tests on the total entrance test scores (X1).

Initially, he took two sub-tests scores—intelligence test scores (X2) and

professional awareness scores (X3)—and derived the necessary

correlations. Compute the multiple correlation coefficient for

measuring the strength of relationship between X1 and (X2 + X3), if

r12 = .80, r13 = .70 and r23 = .60.

Solution. The multiple correlation coefficient

R1.23 =

U U U U U

U

=

– – –

=

=

= 0.845

[Ans. Multiple correlation coefficient = 0.845.]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/stats-s-241206101830-e3d4cc67/75/Stats-S-K-Mangal-statistics-textook-in-pdf-249-2048.jpg)